Bangladesh is globally recognized for dramatically increasing access to educational opportunities, especially for girls and women, over the past few decades.

Bangladesh is globally recognized for dramatically increasing access to educational opportunities, especially for girls and women, over the past few decades.

“The way I had to struggle, I hope other women do not struggle as much. I want to help women find jobs and advance themselves,” Jenatul Ferdous Min says, expressing not only ambitions for herself but for all Bangladeshi women.

Bangladesh is globally recognized for dramatically increasing access to educational opportunities, especially for girls and women, over the past few decades . However, the reality remains that most women are unable to complete post-primary education or make the school-to-work transition to good jobs.

Evidence suggests that Bangladeshi families continue to invest more in post-primary education for boys. Girls are more likely to be involved in both household and income-generating activities while in school, leading to greater absenteeism and poorer educational outcomes, both of which are triggers for dropping out of school. In addition, early marriage continues to negatively impact girls’ attendance and completion rates.

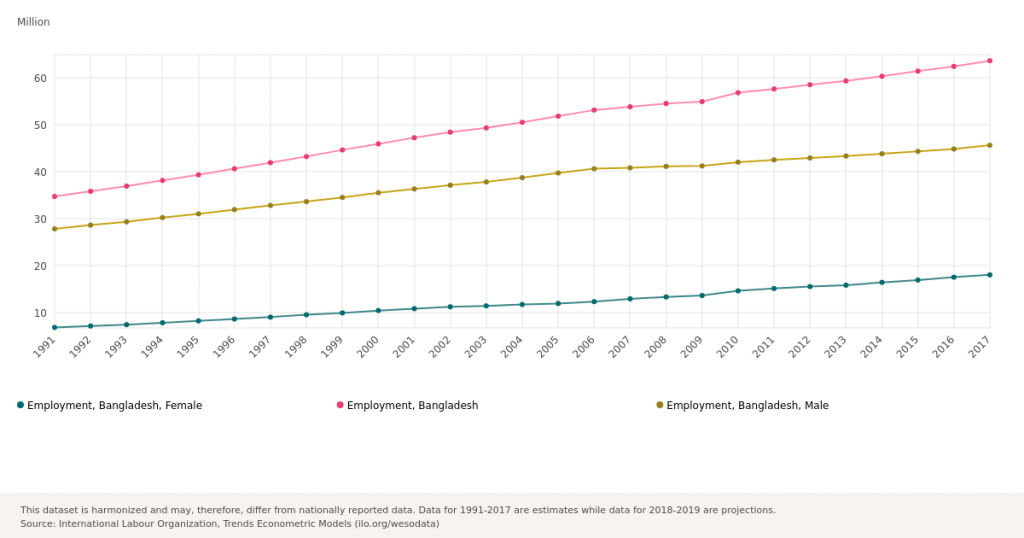

Industries with higher numbers of female workers are facing the prospect of increased automation and the elimination of 40-60 percent of jobs over the next 20 years. Additionally, low-skilled workers face substantially more risk of job loss than those with secondary or tertiary schooling, again disadvantaging women. Economic shocks brought about by COVID-19 and climate change provide an additional layer of vulnerability for female workers, further highlighting the persistent intersectionality of gender and poverty.

Learning from past triumphs to guide future successes

Bangladesh is a girls’ education success story. In 1970, just prior to independence, girls made up only about 17 percent of secondary school enrollment (grades 6-12), yet by the turn of the century, girls made up more than half of secondary school enrollment.

Bangladesh’s high fertility rate, which peaked at just under seven children in the early 1970s, presented a demographic challenge to which the country responded by attracting more girls into the education system through increased recruitment of female teachers. Increased female participation in education was a contributing factor in the reduction of early marriages and falling fertility rates, complementing interventions made by family planning and reproductive health.

Of great importance to the trajectory of girls’ education in Bangladesh was the emergence of the garment industry which dramatically increased the demand for laborers, primarily female, with a basic level of education. Bangladesh responded with an increased supply of education services which responded to a demand from Bangladeshi families to educate girls.

Confronting Today’s Education Challenges

Amid the threat of human capital reversals due to COVID-19 and climate change, sustained investments would accelerate human capital formation and protection. Improved access to quality education and training for all is needed for Bangladesh to benefit from a possible demographic dividend. Women must enter the labor market and earn good incomes for the dividend to be reaped, and for that to be realized, among other factors, girls and women require a quality education. This means a better integration of the skills necessary to ensure employability in the future, including in the green economy, such as information and communications technology (ICT), problem solving, numeracy, and literacy skills in technology rich environments. Also critical are even deeper transformations to societal norms, such as increased commitment to educating girls and women, doubling down on efforts to ensure women’s smooth school-to-work transitions to steady jobs, and women having the agency to safely work outside the home. Despite successes, more and better public investments for education are needed.

The government has strong initiatives in place to support girls and women to access education and job opportunities. For example, the World Bank supports retention of girls and children from poor households in secondary schools through the Transforming Secondary Education for Results Operation (TSER). Through two new investment projects financed by the World Bank, the Higher Education Acceleration and Transformation Project (HEAT) and the Accelerating and Strengthening Skills for Economic Transformation Project (ASSET), the government is improving the employability of university graduates, building a network of women’s universities and colleges, and strengthening Bangladesh’s COVID-19 response in higher education and equipping women with skills needed for the future of work and supporting key industries to re-train workers to accelerate pandemic recovery. Approximately 600,000 female students are expected to benefit from HEAT project activities while over 285,000 women stand to benefit from ASSET project activities. Bangladesh has also committed to policy reforms to strengthen the relevance of skills development, and to help strengthen the regulatory environment for childcare through the Third Programmatic Jobs Development Policy Credit. This support creates opportunities for employment for skilled women, while also supporting services that address the care responsibility constraint that many women face in being active in the labor market.

The World Bank remains a committed financing, knowledge, and policy dialogue partner to enhance girls’ and women’s empowerment through better education, training, and jobs. Coupled with the country’s own sustained efforts and investments for children and young people, Bangladesh can continue to be a regional and global success story.

Join the Conversation