Available in Bahasa

Since the UN’s High Level Panel announced its vision for the post-2015 development agenda in May, much debate has centered on the absence of a goal for inequality among the panel’s list of 15 proposed goals. Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, commenting on the goals in Jakarta last June, stressed that the principle of “no one left behind” was central to the panel’s vision, and that each of the U.N.’s goals focused on tackling inequality. The proposed education goals, in fact, include a commitment to ‘ensure every child, regardless of circumstance, completes primary education able to read, write and count well enough to meet minimum learning standards’.

Efforts to narrow education inequality are vital and can lay a foundation for more inclusive growth. Differences in the quality and duration of the education children receive can fundamentally affect their future livelihoods. Children who fail to master basic skills are more likely to end up in an insecure, low-paid job, as compared to children who leave school equipped with the skills needed in current labor markets.

Yet in most countries, large disparities in educational attainment remain the norm. Indonesia is no exception. A poor child born in Papua leaves school with approximately 6 years of education, compared to a child in Jakarta who can expect to complete 11 years of schooling. Differences in learning achievement can be equally stark; junior secondary school students in Bali averaged 80% in the national examination, compared to students in parts of Kalimantan who scored less than 60%.

Much of the global discourse highlights the lack of resources and their unequal distribution as a key cause of education inequality. But this is only part of the story in Indonesia. In the last decade, public investment in education has tripled in real terms --a rate of increase not seen in many other countries. Some of the poorest districts spend large sums on education for each school-aged child. For example, some districts in Papua, one of the poorest provinces in Indonesia, spend nearly as much as countries in Eastern Europe that rank far higher on international assessments of learning achievement.

So, what can a middle income country like Indonesia do to address education inequality?

The World Bank’s Indonesia country office recently released a survey of education governance quality in 50 Indonesian districts that argues that any attempt to narrow inequality must focus on strengthening the capacity of local governments to deliver quality education services to all children.

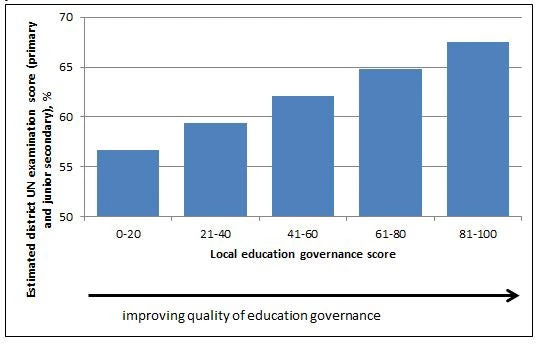

Since decentralization reforms were introduced in 1999, district governments have been responsible for the provision and most of the financing of basic education. The report shows that the priority given to education, the quality of the inputs supplied, and their distribution tend to be better in districts with higher quality governance. Moreover, districts that enable local participation in planning processes build more transparent and accountable systems of management; improve incentives for education staff tend to produce better outcomes; and ensure teachers are better equipped to provide quality education for all.

Higher quality local education governance is associated with better education performance

Yet the study also found that local education governance had improved little over the last three years. In some areas, governance had even backtracked. For example, the number of districts with effective systems for documenting and disseminating good practice appeared to have declined significantly. Planning practices also appeared to circumvent efforts to increase local community participation. For example, in 2012, only 12% of districts consolidated school development plans to use in their district education planning process.

The districts participating in the study also took part in a Ministry of Education program designed to strengthen capacity. While the study highlights some gains at the school level, improvements in district-level management were more modest. Two important lessons emerged from the experience of implementing a capacity building program of this kind:

First, a multisectoral approach to capacity building is needed. District education officers recognized that many key challenges are related to district-level systems (e.g. planning and budgeting systems) rather than specifically to the education system. However, the district education office is often powerless to address these broader constraints.

Second, capacity building efforts need to be tailored to local circumstances. Strengthening governance is easier in some districts than others. For example, publicizing information on the education budget is much easier in a well-connected district with a vibrant local media than in a remote location with limited infrastructure. To be successful, future capacity-building programs need to take account of the specific constraints that districts face.

The big message is that strengthening the management and governance of district education systems can help narrow education inequality. It can also help Indonesia lay the groundwork to ensure that no child is left behind as the new development agenda gets under way.

Related:

Join the Conversation