Quality education is one of the most powerful instruments for reducing poverty and inequality; yet it remains elusive in many parts of the world. The Programme for the Analysis of Education Systems (PASEC), which is designed to assess student abilities in mathematics and reading in French, has for the first time delivered an internationally comparable measure around which policy dialogue and international cooperation can aspire to improve. The PASEC 2014 international student assessment was administered in 10 countries in Francophone West Africa (Cameroon, Burundi, Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Chad, Togo, Benin, Burkina Faso, and Niger).

The results of PASEC provide—for the first time—an internationally comparable perspective of what primary students have learned across the 10 Francophone African countries that participated. The expanded PASEC was implemented as a critical element of the push to promote results-based education sector governance in Francophone African countries and to focus policy dialogue on learning outcomes. By overlaying PASEC results with the latest school participation data from household surveys, one is able to gain valuable insights into how many children are completing primary with the needed skills.

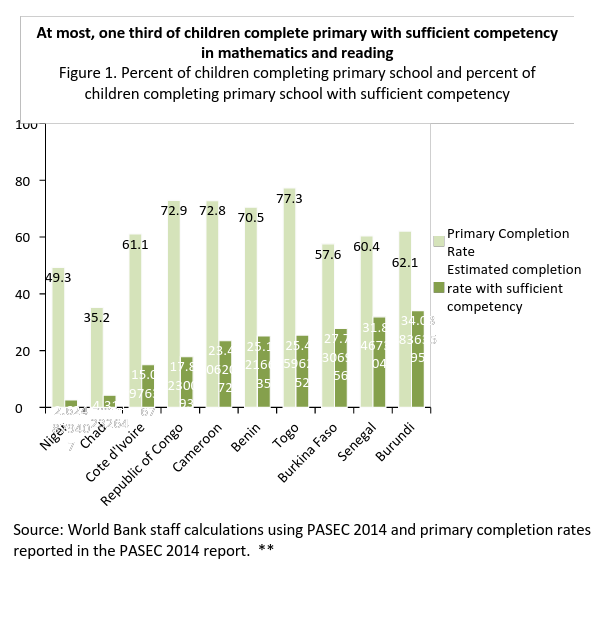

I find the picture alarming. Despite notable gains in expanding access, countries in the region still face a great challenge in providing a quality education for all. Fewer (and in some countries, much fewer!) than one third of children complete primary with sufficient competency in mathematics and reading. For the poorest, the results are much worse.

Children who do not attain sufficient competency in Grade 6 mathematics are unable to perform arithmetic involving decimals or identify a basic mathematical procedure needed to solve a problem. In reading, they are unable to understand explicit information orally or understand the meaning of many printed words.

Across the region, 71 percent of children in Grade 2 do not achieve a sufficient level of competency in French language skills; these children are unable to understand explicit information orally or understand the meaning of many printed words. In addition, 59 percent of children in Grade 5 do not achieve sufficient competency in mathematics. This means that they are unable to perform arithmetic involving decimals or identify a basic mathematical formula needed to solve a problem.

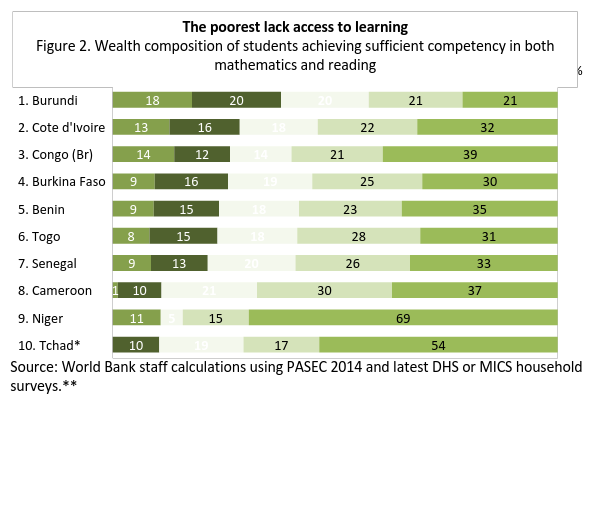

PASEC results also highlight the stark differences that persist between the poorest and wealthiest children that persist: For example, the difference in language achievement between late primary children with literate parents and illiterate parents is nearly a full standard deviation in Benin, Cameroon and Togo

Four key takeaways from PASEC 2014

Less than one third of children finish primary education with sufficient competency in Francophone Africa as measured by PASEC. The implications of this are significant, as education provides a key pathway out of poverty, and research has shown that education quality, not just quantity is critical to reaping the benefits. The majority of youth are not acquiring the skills needed to succeed.

The poorest 40 percent are underrepresented in the group of students who meet PASEC competency standards. This gives us a view beyond just getting the poorest children into schools, as to whether the poorest are experiencing the benefits of learning. This underrepresentation of the poor in achieving learning outcomes may be driven by a variety of factors such as policy decisions, learning inputs and different student experiences, and merits further investigation to inform policy making.

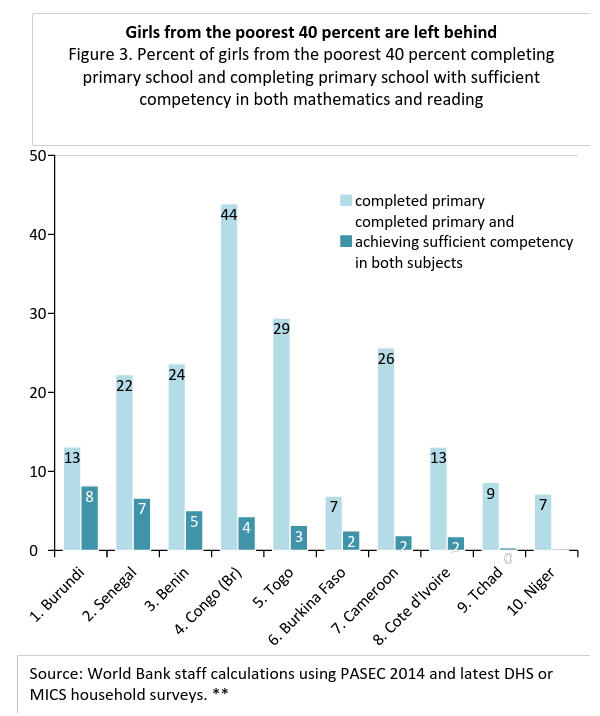

Countries in Francophone Africa still have a long way to go in educating their poorest girls.

In the best performing country, Burundi, only 8 percent of girls from the poorest 40 percent complete primary with sufficient competency in both subjects. The average for the 10 countries is only 3 percent. This finding highlights the challenge that the poorest and disadvantaged girls still remain some of the most marginalized from accessing a quality education, and may be disproportionately affected by barriers such as cultural norms, inadequate service delivery and infrastructure, and lack of security.

Improving education for the poorest is fundamental to poverty reduction, but more must be done to ensure that education outcomes include learning the skills needed to succeed. The economic benefits of education, especially for the poorest, are well documented; but when the poorest are excluded from education—either from school access or from learning when in school—the cycle of poverty perpetuates.

The significant progress Francophone African countries have made expanding access to education is well documented in household surveys and national education data. And with PASEC’s internationally defined standard for learning achievement, progress can now be monitored for what matters in education: learning.

The questions now are "How do we improve learning outcomes?" and "What will it take for policy makers countries to translate their commitments to action?" With so many children in Francophone Africa leaving school for the labour market either during or just after primary level, the quality of primary education is paramount to labour productivity and subsequently poverty reduction. The education results offered by PASEC and other assessments will be vital to inform evidence based policy and investment decision making.

While there is definitely room for improvement, PASEC has for the first time delivered an internationally comparable measure around which policy dialogue and international cooperation can aspire to improve.

**For more information on country outcomes and detailed notes on calculation of data please visit the PASEC country report cards here .

Find out more about World Bank Group education on Twitter and Flipboard .

Join the Conversation