For a region that is considered middle-income, it is unacceptable that one in every 40 children in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) dies in the first year of life mostly from preventable causes. Neither does it makes sense that one fifth of its youngest population is stunted from malnutrition, and more than half are missing out on critical micronutrients such as iodine in salt, which impairs cognitive development. Moreover, with only 27 percent of children ages 3-5 enrolled in pre-school, almost half the world average, three quarters of children in the region are missing the opportunity to build the foundations for school readiness, and to acquire the skills they will need to lead a happy, autonomous, and healthy life.

What are the implications of these alarming trends?

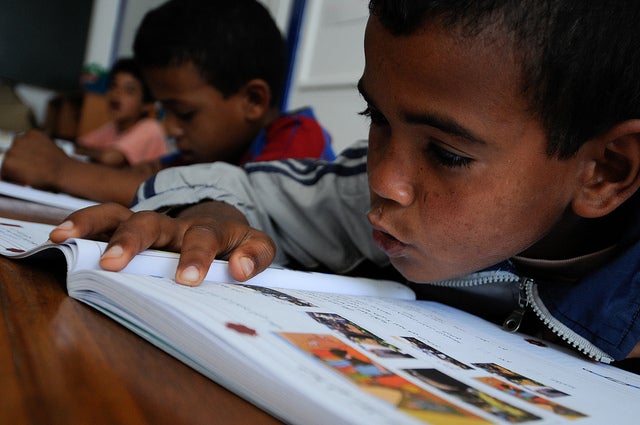

Research shows us that early nutrition and psychosocial stimulation in the first years of life are vital for brain development and healthy growth. There is also robust evidence that early childhood development (ECD) programs, which target children under the age of 5, yield significant positive impacts over a lifetime, particularly when compared to investments made later in life. Some examples include programs that promote health and nutrition, parenting education, preschool enrollment, and children's educational media.

We also know that inequality begins in early childhood and that deficits early in life are difficult and costly to remediate later in life and tend to perpetuate cycles of poverty and inequality.

A new World Bank report has compiled a comprehensive set of data from across the region on the state of ECD. It finds that investments in ECD are some of the lowest in the world, and that there is also large inequality of opportunities among children in all of the region’s countries. A child from the richest homes in Tunisia, for example, has a 97% chance of attending early childhood care and education, while a child from the poorest homes has only a 4% chance.

Global experience has also shown that interventions directed at the poorest children can offset negative trends, as well as promote quality learning and physical growth. In fact, investing in young children is one of the smartest investments a country can make.

In a context of increased conflict, political instability and wide-spread violence throughout the region over the last few years, policymakers might consider ECD investments a luxury rather than a necessity. But we would argue the contrary: ECD is a critical and urgent investment especially to address severe challenges in human development, social stability, and equitable growth. Therefore, not investing in ECD right now in the MENA region would be extremely short-sighted as it would lead to costly and often irreversible consequences for the upcoming generation.

The key question is: how can we use the data on early childhood development to work together with policymakers to create programs and expand their coverage at a low enough cost that it is affordable and sustainable?

We would like to suggest five key considerations for policymakers to achieve maximum impact:

- Campaigns to reach the whole family with parenting messages, not just the mother. All household members who are involved in decisions about childrearing and/or engaged in daily interactions with the youngest family members (e.g., fathers, grandmothers, mothers-in-law, and siblings, among others) should be aware of the importance of adequate nutrition and early stimulation for young children.

- Keep the quality of services in mind: Scaling up center-based care (including daycares and preschool) can promote children’s development, while at the same time freeing up mothers’ time for engaging in further education or income-generating activities. Yet families will stay away and participating children will not benefit, defeating the purpose of the centers, if the quality of care and education is below certain standards.

- Implement ECD inclusively. Many disabilities emerge in early childhood and, if left undetected or un-addressed, can accentuate inequities. MENA countries now have an opportunity to scale up their ECD investments in ways that promote early detection of disabilities, establish linkages with additional services as needed, and offer inclusive center-based care.

- Partner with non-state actors. Scaling up ECD investments in a way that reaches the most vulnerable with quality programs can seldom be done through state systems alone. Policymakers should explore mutually beneficial partnerships with the private sector, NGOs, faith-based organizations, media, and others to reach additional segments of the population and promote behavior change, including the use of technologies such as cell phones, television, or radio programming.

- Avoid letting the best become the enemy of the good. Building multi-sectorial strategies, policies, and programs that truly address the holistic needs of young children (health, nutrition, social and cognitive development) are indeed important, but can take a while. In the meantime, countries should consider choosing one or two “strategic entry points,” such as parenting programs to increase early stimulation or center-based care, and progressively build from there.

Follow the World Bank Group Education team on Twitter @wbg_education

Related:

Join the Conversation