One of the biggest economic benefits of schooling are labor market earnings. For many people, education and experience are their only assets. This is why I believe that it’s very important to know the economic benefits of investments in schooling.

The rate of return equates the value of lifetime earnings to the net present value of costs of education. For an investment to be justified, the returns should be positive and higher than the alternative. For the individual, weighing costs and benefits means investing as long as the rate of return exceeds the private discount rate.

Where the returns to schooling are highest and lowest

The global private rate of return to schooling is 10% for every year of schooling. This recent estimates comes from data from 139 economies. The returns are highest in Sub-Saharan Africa, namely in Ethiopia, South Africa and Tanzania.

The returns are lowest in the Middle East and North Africa. While the relationship between schooling and earnings does not necessarily imply causality, evidence from natural experiments to increase schooling confirm that the effect of ability and related factors does not have a significant impact on the general results for returns to education. I believe that schooling does indeed impart skills that enhance productivity. Increases in earnings are also due to the increased productivity brought about by investments in human capital.

Modest declines in the returns to schooling

Though the returns to schooling decline as the supply of schooling in a country increases, they tend to decline only modestly over time. In fact, they decline by no more than two percentage points in a given decade, and more recently much less than that.

Using global data, returns to schooling are shown to have declined significantly over time, but at a much slower rate than has occurred with the expansion in schooling, especially since the late 1990s. While the supply of schooling expanded by almost 50 percent worldwide since 1980, the returns to schooling declined by only 3.5 percentage points, or 0.1 percent per year. At the same time, the average length of schooling increased by more than three years, or two percent per year worldwide. On average, another year of schooling leads to a reduction of the returns to schooling by one percentage point.

Gender and the returns to schooling

The returns to schooling are higher for women at all levels of schooling. The overall rate of return to another year of schooling for women is 12 percent and only 10 percent for men. At the primary school level, the returns are about the same. At the secondary and tertiary levels, the returns diverge, with higher returns for females at the secondary and tertiary levels.

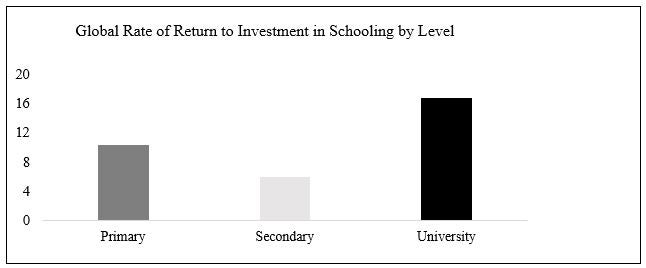

In a stunning reversal, the private returns to university education are now higher than the returns to primary schooling

The returns to primary schooling are above 10 percent, and they decline sharply at the secondary level to just over seven percent before jumping to 15 percent at the tertiary level. Still, the returns are higher in Sub-Saharan Africa at all levels.

There are variations by region: there are high returns to primary schooling in the Middle East and North Africa (especially for females), while the returns to tertiary are low. Returns to primary schooling are surprisingly low in South Asia.

To some extent, the effect on primary education may be driven by an increase in compulsory education. That is, as countries develop and education systems expand, primary school becomes compulsory and universal, making it difficult or impossible to estimate returns to education, or to compare them to older workers who may have lower wages for other reasons.

Social rates of return are higher in lower income countries where the quantity of schooling is scarcer.

While the biggest change in the patterns observed is that the private returns to primary education are no longer the highest, social returns estimates suggest a need to nuance conclusions. There are low returns to primary education in upper middle income countries because primary education has reached most of the population. It may also mean that given near universal coverage of primary education in these countries there is no much room to further expand this level of schooling. It might instead make sense to increase investment in the quality of primary schooling.

The rate of return to schooling is well above any alternative investment

For the individual, it makes sense to invest in schooling, which has a positive returns and is above any competing alternative. This includes government bonds, stocks, bank deposits and housing investments. It also makes sense for governments to invest in education, since social returns are also higher than alternatives, including investments in physical assets.

The pattern of the returns to education have several policy implications

The first is that there is a continuing need to focus public investment on the poor. The returns to primary schooling may be falling because the quality is poor. If the quality is poor, then access to the secondary and tertiary levels for the poor will slow down and higher returns at the tertiary level will lead to growing inequality. Focusing on the social returns to education, primary education is an investment priority in low income countries, followed by secondary and tertiary in this order.

The second implication is to invest in education quality. The focus on basic education emphasized access and not enough attention has gone towards quality. Access to basic education increased considerably over the last few decades.

To expand access and quality at the secondary level, alternative finance models may be needed to reach the poor in remote and rural areas. Special measures may be needed to increase enrollment among ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples in some countries, such as bilingual education or tailor made delivery modes.

The much higher cost for secondary education, especially at the upper level, may require the use of public-private partnerships – for example, industry links for skills formation and charter schools to reach the poor and disadvantaged, vouchers to encourage enrollment to complete secondary.

The third implication is that higher education should be expanded. High returns to tertiary signal that university is a good private investment. Fair, equitable, sustainable cost-recovery at the university level is warranted. The difference between private and social rates of return, especially for tertiary education, calls for innovative financing mechanisms that will expand access and effective demand for enrollment, especially among the poor. Such mechanisms may include but are not limited to: selective cost-recovery, income contingent loans and human capital contracts.

Can you think of other policies that can improve the returns to schooling in your country? Do share in the comments section below.

Follow Harry Patrinos on Twitter at @hpatrinos.

Find out more about World Bank Group education on Twitter and Flipboard.

Join the Conversation