Vietnam’s education system is receiving a lot of international attention following the country’s strong performance in the 2012 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). Vietnam’s 15 year-olds performed as well in mathematics, reading and science as their peers in much richer Germany and Austria, and better than the international average. In an earlier blog I reviewed possible explanations for this success.

New analysis of data for Vietnam from the World Bank’s Skills Toward Employment and Productivity (STEP) skills measurement surveys confirms the message from PISA.

The STEP household survey measures reading literacy of adults aged 15-64 in urban Vietnam, among other things. Its reading assessment results can be placed on the same scale as, and are broadly comparable with, the reading assessment of the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), which also measures reading literacy for adults aged 16-65 across many richer countries (and not just urban). There are two noteworthy findings:

First and as perhaps expected, adults in urban Vietnam overall perform less well in reading literacy than adults in richer industrialized countries (Figure 1).

Source: Vietnam estimates from World Bank staff analysis using STEP household survey data. Literacy scores from other countries were measured as part of the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies.

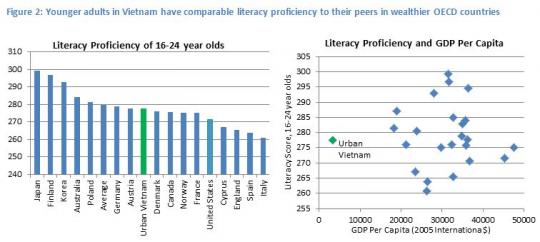

Second, these averages hide significant variation across age cohorts. When looking at the youth population, Vietnam’s performance is much more impressive. Urban Vietnamese workers aged 16-24 performed as well in the STEP reading assessment as their peers in Austria and Germany did in PIAAC, and better than those in much richer countries (Figure 2). This is remarkably consistent with the PISA findings. However, some caveats apply: STEP captures urban workers only while PIAAC has a national sample. And urban workers might have better-than-average reading skills. A similar bias affects PISA, which captures 15 year-olds in school and not those (likely weaker) students that have already dropped out.

Source: Vietnam estimates from World Bank staff analysis using StEP household survey data. Literacy scores from other countries were measured as part of the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies.

Nevertheless, Vietnam’s significant investments over the past 20 years in expanding access and quality of education have paid off in terms of significantly better skills among the youth today. Vietnam’s success story can serve as an instructive case study for other middle income countries. My colleagues Reena Badiani-Magnusson, Kevin Macdonald, David Newhouse, Jan Rutkowski and I have just finalized a study (“Skilling up Vietnam: Preparing the Workforce for a Modern Market Economy”), which reviews Vietnam’s education system from early childhood to tertiary education and lifelong learning, and proposes options on how to capitalize on its achievements so far. It can serve as a reference for those who want to know more about Vietnam’s case.

The study documents the evidence of impressive basic literacy and numeracy achievements of Vietnamese students and young workers. But it also reveals that many Vietnamese businesses consider a shortage of workers with adequate skills as a significant obstacle to their activity. Drawing on the STEP survey, the study finds that, in addition to job-specific skills, Vietnamese employers value cognitive skills, such as problem solving and critical thinking, and behavioral skills, such as team work and communication. Reorienting Vietnam's education system toward teaching these types of skills will help prepare Vietnamese workers for a modern market economy.

Vietnam’s reformers are already at work to make this a reality. For example, discussions on curriculum reform for primary and secondary education to strengthen the development of cognitive and behavioral skills are under way. They draw on lessons from a Global Partnership for Education-financed pilot of alternative teaching methods in 1000 Vietnamese primary schools, adapted from Colombia’s Escuela Nueva. It appears that Vietnam will remain an interesting case to watch over the coming years.

Related:

Join the Conversation