South Asia is highly vulnerable to climate change—including floods, extreme heat, and sea level rise. The burden of adapting to climate change falls disproportionately on poor households, which are typically more vulnerable to climate shocks. Globally, research on climate change identifies a variety of adaptation strategies by households, firms, and farmers, which have the capacity to offset nearly half of climate damage, on average. Firms have access to successful technology-driven adaptations, whereas households and farmers rely on less effective labor market adjustments. Adaptations that involve public support tend to be more effective than purely private strategies. Investing in broad public goods and social transfers that generate double dividends can help build resilience to climate change.

1. South Asia is highly vulnerable to climate disasters

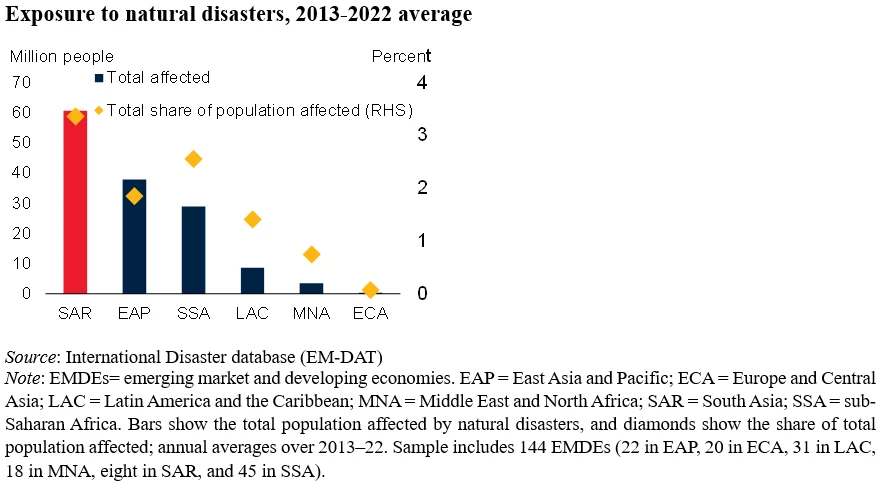

South Asia is the emerging market and developing economy (EMDE) region that is most vulnerable to climate change. This reflects South Asia’s geography, which leaves it exposed to changes in groundwater availability, floods, extreme heat, and rising sea levels. About 60 million people per year have been affected by natural disasters in South Asia since 2013, more than in any other region in the world. Climate change is projected to reduce agricultural yields, industrial output, labor supply, productivity, and human capital in South Asia.

2. Globally, the poor tend to be more exposed to, and affected by, climate disasters

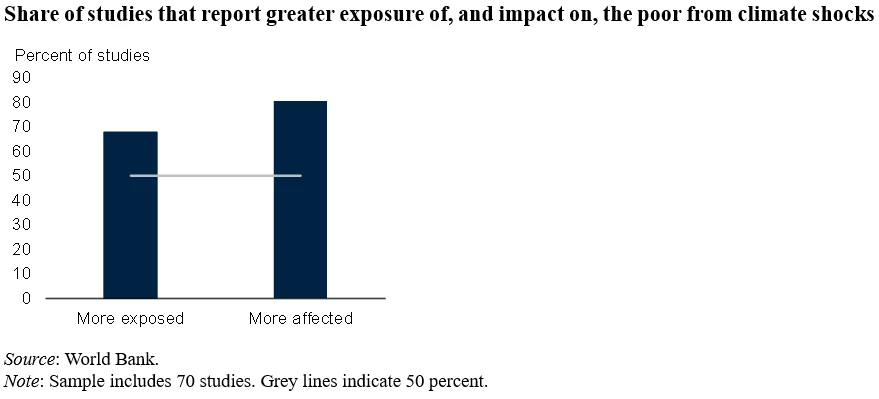

In a systematic literature review, two-thirds of studies found that the poor are more exposed to climate shocks. Studies of droughts, heat, and floods in particular were likely to find the poor were more exposed to climate than average households. Furthermore, 80 percent of studies found that the poor were more adversely affected by climate shocks than other households. The poor typically suffer greater income and human capital losses from climate events and will disproportionately bear the burden of private adaptation to climate change.

3. Adaptation can work, but effectiveness varies substantially across domains

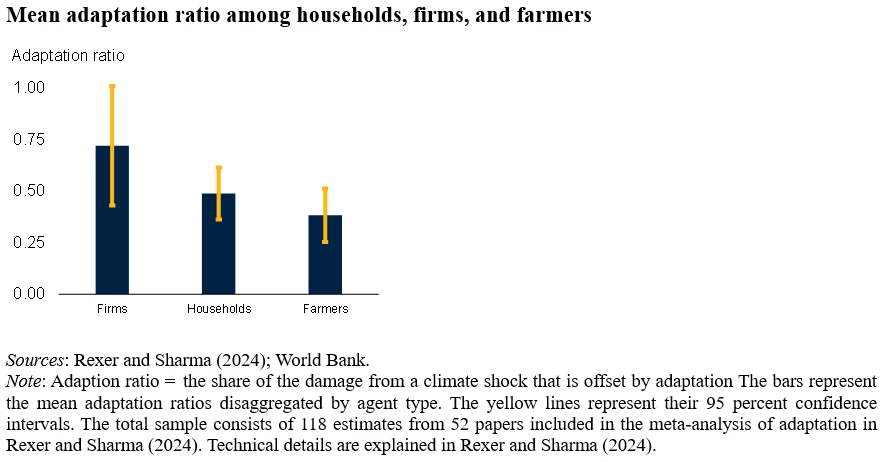

Households, firms, and farmers adapt to climate change in myriad ways. Factories may adopt cooling technologies to prevent productivity losses during heat waves; farmers may plant drought or flood resistant varieties to boost yields; households may migrate or seek employment in less climate-exposed regions or sectors. The degree to which these behaviors offset the damage from climate change is called the adaptation ratio. A recent systematic literature review finds that, on average, such adaptive behaviors offset 46 percent of the damage from climate change. However, adaptation ratios vary widely across settings: while firms recover 72 percent of climate losses, this number falls to 49 percent for households, and just 38 percent among agricultural producers.

4. As a middle-income region, adaptation in South Asia is likely to be effective

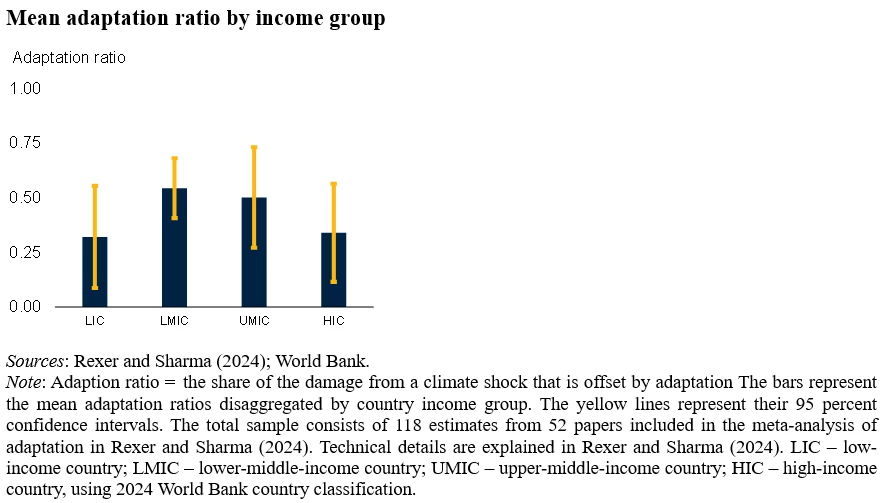

Adaptation ratios also depend on income levels. The lowest adaptation ratios are in low- and high-income countries, which offset only 32 and 34 percent of climate losses, respectively. In contrast, in middle-income countries adaptation mitigates over 50 percent of climate damage. In low-income countries, constraints to adaptation may be severe, and so observed adaptations tend to be less effective. In advanced economies, the most effective adaptations may already be widespread, reducing the impact of an additional adaptation. In middle-income countries, however, there may be both fewer constraints to adaptation than in low-income countries, and more low-hanging fruit than in high-income settings.

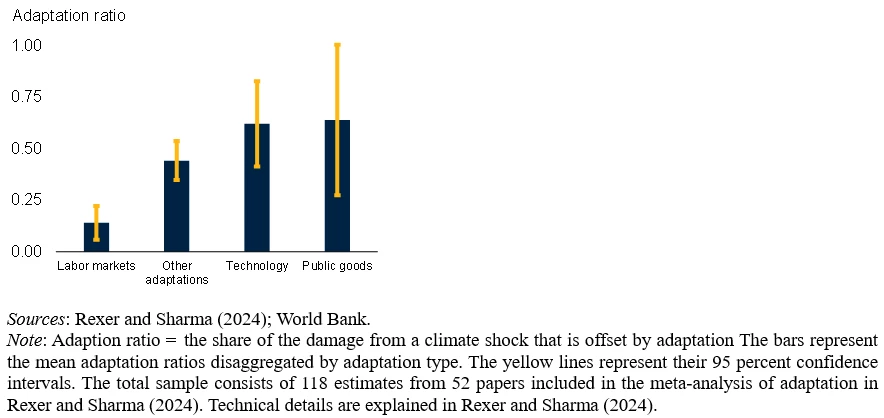

5. The choice of adaptation strategies matters

Not all adaptation strategies are created equal. Labor market adjustments, the most common adaptation among households, are the least effective, offsetting just 14 percent of climate-related economic losses. Migration, off-farm work, and other labor market choices have low barriers to adoption and are commonplace among the world’s poor, but broadly ineffective in the face of rising climate risks. In contrast, state-provided public goods have the highest adaptation ratio of all studied adaptation strategies. These public goods are generally not climate-specific investments, but rather comprise the standard set of goods and services typically provided by the state—roads, bridges, health systems, irrigation canals, piped water. For example, connective infrastructure can reduce hunger during droughts by improving market integration, while a strong health system can reduce the impact of heat on infant mortality. These public goods not only serve their primary function, but also improve resilience to climate change, generating double dividends. Technological solutions, often favored by firms, are also highly effective.

Join the Conversation