India Gate, New Delhi on a hazy morning. Pollution level rises and causes smog in autumn due to stagnant winds. Photo: Shutterstock/ Amit kg

India Gate, New Delhi on a hazy morning. Pollution level rises and causes smog in autumn due to stagnant winds. Photo: Shutterstock/ Amit kg

South Asian cities are known hotspots for air pollution. But in the last few months, many have enjoyed unusually clear skies and fresh air.

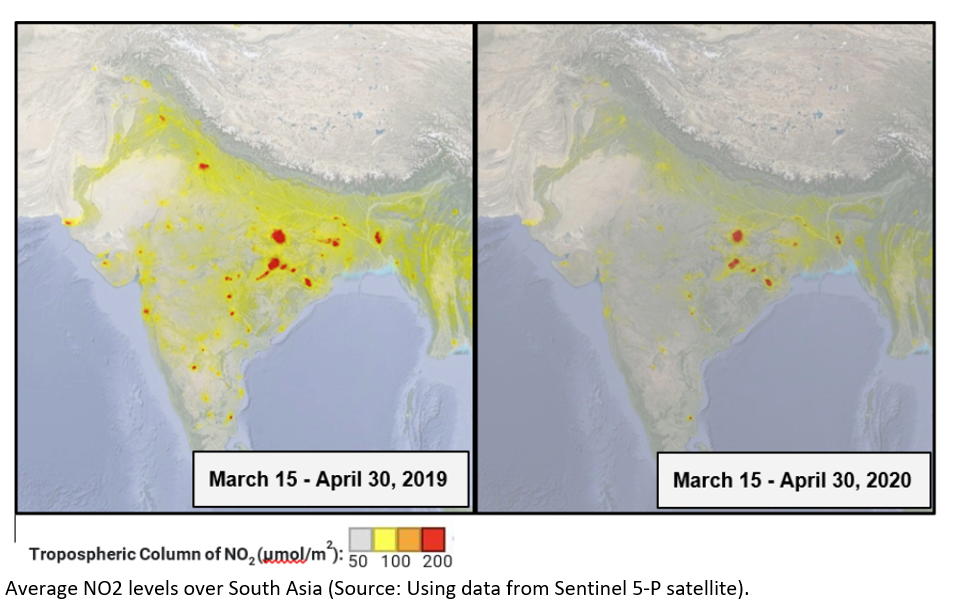

When countries started enforcing lockdowns to contain the coronavirus (COVID-19), metropolises across the region recorded significantly lower levels of nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide , both harmful chemicals released in part by motor vehicles and power plants.

Cities with historically high particulate matter (PM2.5) concentration levels also experienced a substantial reduction in pollution—although further analysis is needed to determine whether natural sources or human activities explain this decrease.

Despite the welcome respite, air pollution has long been a major public health threat in South Asia, representing the third-highest risk for premature deaths.

Ambient pollution reduces life expectancy on average by 1.87 years in Bangladesh, 1.56 years in Pakistan, and 1.53 years in India. Pollution is especially severe in fast-growing urban areas, which combine high population density with a large number of motorized vehicles and construction work, uncontrolled solid waste burning, and heavy use of polluting sources of energy.

When countries enforced lockdowns to contain COVID-19, metropolises across the region recorded significantly lower levels of nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide

South Asia is also among the world’s regions most exposed to household air pollution. About 79 percent of the population in Bangladesh, 60 percent in India, and 52 percent in Pakistan are exposed to pollution from burning of solid fuels, which contribute significantly to poor health in the region.

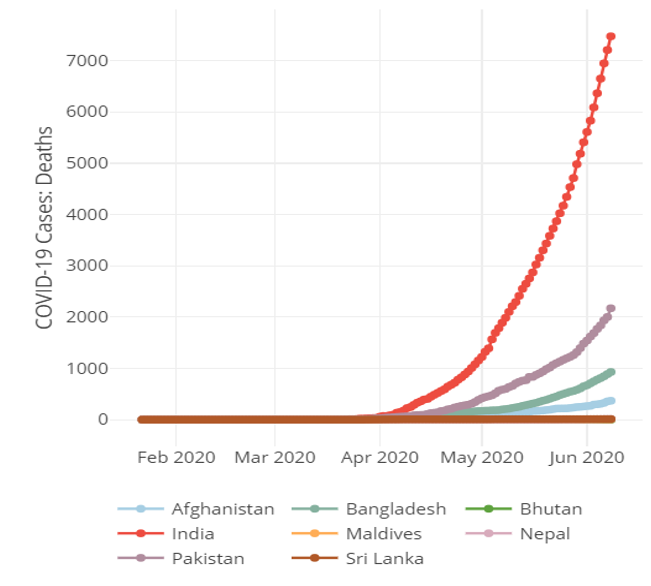

While lockdowns have provided the temporary side benefit of cleaner air and bluer skies, previous exposure to pollution has likely made more South Asians vulnerable to contracting severe respiratory diseases, including complications from COVID-19. As of June 22, COVID-19 cases in South Asia have been rising exponentially, with more than 735,000 confirmed so far, mostly in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

Medical experts place vulnerabilities related to respiratory ailments such as asthma and chronic lung disease high on the list of preexisting conditions that can make people more susceptible to COVID-19. Among the first hospitalized patients, pneumonia, sepsis, respiratory failure, and acute respiratory distress syndrome were reported as the most frequent complications.

Researchers around the world suggest that air pollution has significantly worsened the impact of COVID-19 and may have led to more deaths than if pollution-free skies were the norm.

Researchers around the world suggest that air pollution has significantly worsened the impact of COVID-19 and may have led to more deaths than if pollution-free skies were the norm. Scientists posit that harmful air particles found in polluted environments may be predisposing people to the virus. Another theory suggests that these particles may also act as vehicles for viral transmission.

A study in Europe found that 78 percent of the deaths related to COVID-19 in northern Italy and Spain occurred in the five regions that had the worst combination of nitrogen dioxide levels and airflow conditions, which prevent dispersal of air pollution. A high level of correlation between COVID-19 cases and air pollution has also been reported in similar studies in the United States and the Netherlands. However, these are early estimates that warrant a more rigorous analysis.

There is research underway—including ours—that establishes a link between air pollution and COVID-19 in South Asia, using rigorous analytical tools with the most recently available data. The findings could have a significant implication for governments as they ease lockdowns in the coming months and deal with the aftermath of COVID-19.

A scientific consensus seems to be emerging that improving air quality could play an important role in overcoming the pandemic. Although at an early stage, research implies that pollution must be limited as much as possible when lockdowns are lifted to minimize the impact of a second or a third wave of the coronavirus.

These emerging findings also offer an opportunity not only to enforce existing air pollution regulations to protect human health (both during and after COVID-19) but to also ensure that we get out of this crisis with the prospect of less air pollution.

Countries could promote cleaner fuels and adopt more environment-friendly transportation and energy technologies. For example, some cities in Europe are already planning to emerge from the lockdown with cleaner transport options in place.

Join the Conversation