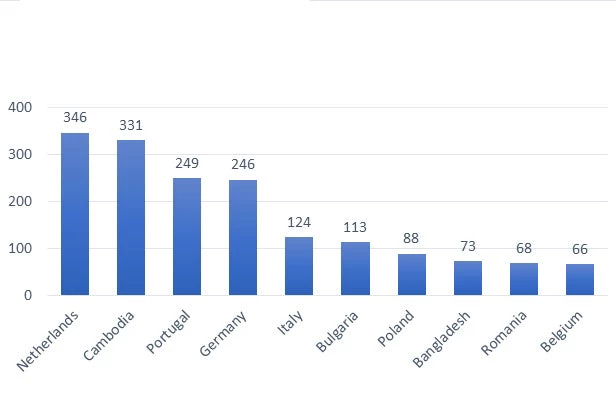

Did you know that Bangladesh is the 2 nd largest non-EU exporter of bicycles to the EU and the 8 th largest exporter overall?

Bicycles are the largest export of Bangladesh’s engineering sector, contributing about 12 percent of engineering exports.

This performance is in large part due to the high anti-dumping duty imposed by the EU against China.

Recently, the EU Parliament and the Council agreed on EU Commission’s proposal on a new methodology for calculating anti-dumping on imports from countries with significant market distortions or pervasive state influence on the economy.

This decision could mean that the 48.5 percent anti-dumping duty for Chinese bicycles may not end in 2018 as originally intended. China is disputing the EU’s dumping rules at the World Trade Organization.

As the global bicycle market is expected to grow to $34.9 billion by 2022, Bangladesh has an opportunity to diversify its exports beyond readymade garments. Presently, Bangladesh is the 2nd largest non-EU exporter of bicycles to the EU and the 8th largest exporter overall.

However, if the EU anti-dumping duty against China is reduced or lifted after 2018, Bangladesh’s price edge might be eroded.

Bangladeshi bicycle exporters estimate that without anti-dumping duties, Chinese bicycles could cost at least 10-20 percent less than Bangladeshi bicycles on European markets. And Chinese exporters can ship bicycles to the EU market with 35-50 percent shorter lead times.

So, how can Bangladeshi bicycles survive and grow?

Bangladesh needs to focus on the bottlenecks that affect the competitiveness of the bicycles sector, especially given its somewhat tenuous situation.

By critically assessing the bicycle value chain in Bangladesh, the World Bank’s Diagnostic Trade Integration study identifies key constraints and suggests policy reforms in that direction.

The bicycle manufacturing sector is split into two: modern, export-oriented original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), and small-scale/cottage bicycles and parts manufacturers catering to the domestic market. There are extremely limited linkages between the two segments. The domestic market has low-quality requirements and is highly protected, which incentivizes local producers to focus on the domestic market. Moreover, local producers lack access to finance and cannot invest in modern tools and equipment to meet higher-quality demand.

Production cost in the export-oriented OEMs is dominated by parts and components, most of which are imported. Although these firms are vertically integrated to partially reduce dependency on imported parts, a limited parts industry affects export prospects. This, coupled with country constraints in trade facilitation and logistics such as port delays and complex customs procedures, is contributing to longer lead times than in other exporting countries like China.

How can Bangladesh become more competitive in a more contested market and break into markets like the United States, Japan and regional urban clusters in South Asia?

Broader policy level support on cross-cutting issues such as trade facilitation reforms can reduce lead times and the cost of doing business. The parts industry will need to invest in modern tools and equipment.

Large OEMs can support such investment by guaranteeing bank loans for their suppliers on the basis of their orders to them. Reducing output tariffs and ensuring minimum quality requirements for the domestic market will narrow the gap between the domestic and export markets, and enable the domestic base of quality products to grow. This would also provide domestic consumers with a choice of higher quality bicycles. Moreover, Bangladesh can seek efficiency-enhancing FDI from countries such as India and China and become part of regional and global supply chains in bicycles and parts.

By activating these critical policy levers and attracting investment, and gradually reducing the quality gap between the domestic and export markets, Bangladesh could see a positive impact on exports and employment in its bicycle sector.

Join the Conversation