Girls at School.

Girls at School.

“In the heart of my village, a government school emerged as a blessing, helping us move ahead and become part of the workforce. Despite an academic atmosphere that may not have ranked as the best, its impact was profound as it helped me study at a university later, and today I work as a lecturer at a private university,” said Muhammad Tariq, a former student of a boy’s government high school in rural Lodhran, Punjab, Pakistan.

We believe that success stories like Muhammad Tariq’s from Pakistan are often overlooked. By highlighting these successes, we aim to demonstrate to policymakers that strategic investments in human development can pay off. With about 20 million children aged 6-16 who are not in school, Pakistan is home to the second largest out of school population in the world. Globally, an estimated 244 million children remain out of school today. Sounds like a policy failure, right? Well, upon reflection, the reality is much more mixed when we consider the challenge of population growth.

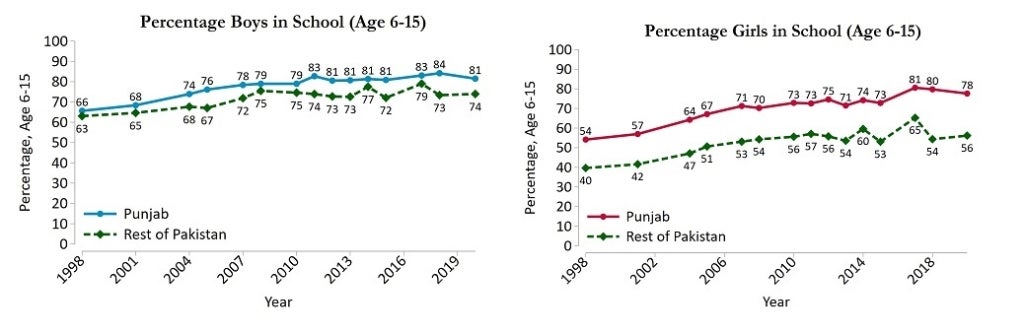

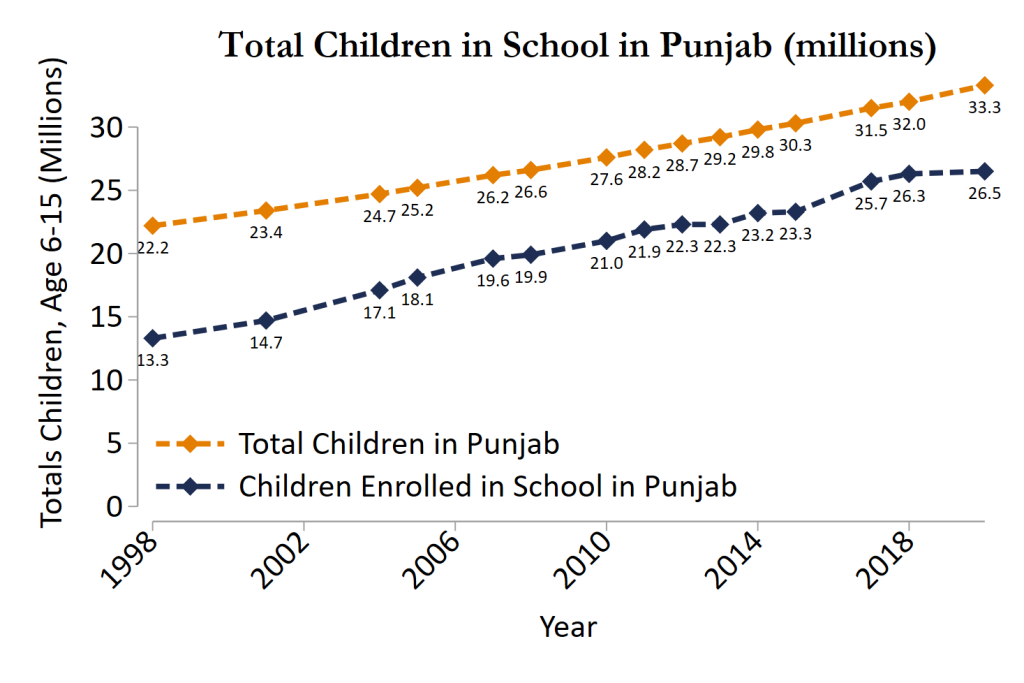

Case in point is the Punjab province, which contains over half of Pakistan’s growing population. Combining census data with household surveys, Punjab expanded schooling from 13 million students in 1998 to 26 million students by 2020 over the last 20 years, effectively doubling the number of children aged 6-15 in school . Household surveys show an increase in the share of children enrolled by about 19 percentage points.

Remarkably, the growth is largest for girls, with an estimated 24 percentage point increase in enrolment --versus 15 percentage points for boys. In other words, Punjab is quickly developing down the path of modernization. How has it achieved these goals and what lessons can we learn?

Punjab’s success dates back to the early 2000s. Successive governments, supported by various donors, have implemented this evolving reform program over several decades. The World Bank alone has invested US$1.5 billion in education and human development programs starting in 2003. But perhaps more importantly, Punjab followed randomized evidence, using data to track progress.

First, at the heart of these series of reforms was sustained political leadership and commitment to education. The Government of Punjab placed school access at the center of the education policy and in 2003, made education free for all at the point of access. This meant that students didn’t pay tuition and received free textbooks. The education reforms received high-level leadership from the Chief Minister of the provincial governments to strengthen service delivery, with regular stock takes at the highest level of government. The Government of Punjab also made institutional changes, creating a monitoring and implementation arm that was independent from the education bureaucracy and devolving financing to district governments through performance-linked budgeting. Key initiatives introduced under the series of reforms were sustained over three political governments, and in collaboration across government institutions and donor partners.

Second, Punjab has made strategic financial investments in programs that were shown to work. The province introduced a ‘non-Salary Budget’ program to allocate and disburse discretionary operational funds to schools, with a formula that included incentives to improve school enrollment and school infrastructure. This program increased resources in public primary schools, with knock-on effects on local private schools, raising enrolment and quality for all schools in covered villages.

The province also provided conditional cash transfers for girls’ education and expanded school participation for girls regularly attending schooling from grades 6-10. This program increased middle school enrollment for girls by 10 percentage points in just two years from 2003 to 2005, increased completion rates by 4.5 percent, and saw transition rates to high school improve as well.

Finally, because the public sector takes long to build new schools and hire new teachers, the province also used budgetary support to scale a Public Private Partnership (PPP) model across the province to provide schooling to about 2.5 million students. An impact evaluation from the neighboring Sindh province found that these types of schools could raise enrolment by 30 percentage points and learning levels by 0.63 standard deviations. Evidence from Punjab shows that PPP schools are located in districts where high shares of children are out-of-school, unlike public and private schools .

Third, the government actively reached out to parents and households through a school council mobilization program. The province leveraged SMS based technology to engage with school council members to motivate them to increase school enrollment and provide them information about their roles, school funds, and quality issues. An evaluation of the program found that student enrollment increased by 5.7% relative to baseline enrollment, with a particularly large increase for girl’s enrollment of 12.4 percent. During the COVID-19 school closures, the government sent out text and voice messages to nearly 7 million families to drive stronger engagement with public schools. These text messages were evaluated through an impact evaluation led by the World Bank and seemed to improve both enrolment and learning outcomes.

Expanding education for 13 million additional children is no small feat. To illustrate, this is the size of a schooling population of an average middle-sized country (Vietnam’s schooling population is about 14 million students, Germany’s is about 12 million children). In other words, the Punjab province now provides new learning opportunities to a cohort that’s equivalent to a major countries’ entire student population! Not for nothing has the Punjab’s reform program been described as having been the ‘most frenetic education reforms in the world’.

Of course, Punjab is by no means done. With an estimated 7 million children still lacking access to school, and prevailing low learning levels, Punjab must continue its reform program. Just like Mohammad Tariq’s journey underscores, we must recognize that the quality of education remains a significant challenge. Yet, there is real progress here, at an impressive scale, much like him children are stepping into classrooms, forging paths to higher education and the workforce. A combination of leadership, and smart investments based on evidence and community engagement, are always good bets to bring more children into school and help them learn.

Join the Conversation