Bangladesh nutrition

Bangladesh nutrition

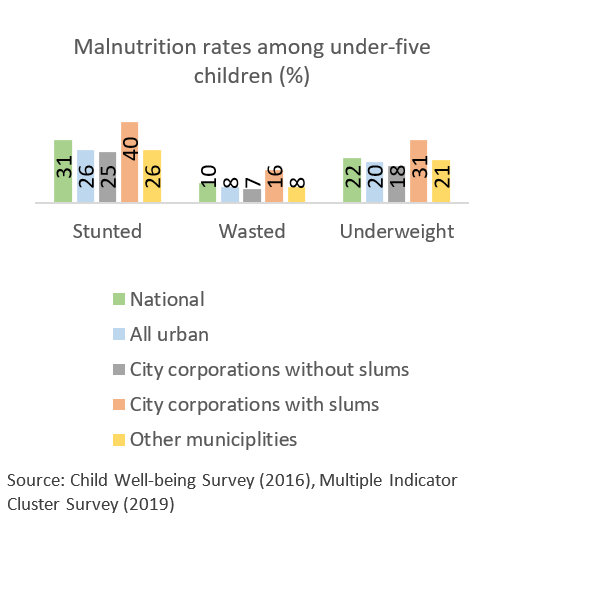

Bangladesh has experienced impressive gains in reducing undernutrition over the past two decades. For example, the proportion of stunted children under-5 fell from 43 percent to 31 percent between 2007 and 2018 while the number of wasted children nearly halved – from 17 percent in 2007 to 8 percent in 2018. These improvements reflect improvements in health service delivery, food security, educational attainment, women empowerment, and environmental conditions.

Although malnutrition is lower in urban areas than elsewhere in the country, increasing evidence, however, shows that there are pockets of poor people in the urban space. They are mostly living in slums and other low-income areas which experience considerably higher malnutrition rates than other parts of the country. For instance, the stunting levels among children under five years of age living in urban slums is 40 percent compared to 31 percent nationally. Twice as many women from poor households (nearly 20 percent) are underweight compared to those from wealthier households. While poverty certainly plays a role, the outcomes such as underweight and anemia are, to a large extent, exacerbated by gaps and the lack of coordination in health delivery service, the absence of policy measures that support nutrition, and a low demand for essential nutrition and health services—such as antenatal care during pregnancy to better manage anemia or child care and feeding practices when a child is suffering from diarrhea or respiratory infections -- due to a general lack of awareness about their importance.

Mind the gaps

So, what are these gaps and what can be done about them? Based on a recent review, we explore some of the key gaps and make recommendations for how they can be addressed:

- The jigsaw of service delivery: Services in the urban space –such as health services and clinics, are delivered by a gamut of multiple ministries, NGOs, and for-profit private facilities. Inadequate oversight or effective coordination mechanisms between these entities result in blurred lines of accountability and suboptimal quality of service delivery. One way to address this issue may be to establish a unified body with relevant stakeholders while also ensuring clear communication lines and referral systems across the facilities.

- Enhancing both supply and demand: The demand for primary healthcare including essential nutrition services in urban areas is low. Low demand is driven to a large extent by gaps in service coverage and lack of awareness of the need for such services, especially among the poor. Expanding and intensifying services so that they are more inclusive of the marginalized and vulnerable in low-income communities and implementing awareness campaigns that generate demand for such services is critical.

- Money matters: The lack of a separate budget allocation for health services or public health initiatives impedes urban governments or city corporations from recruiting sufficiently qualified personnel. This results in facilities operating considerably below their target capacities both in terms of manpower and technical skills. Increasing the allocation of revenue and development budget dedicated to healthcare in urban areas will help strengthen the delivery of nutrition services.

- Targeting for efficiency and spotlighting the less-visible: Absence of effective targeting mechanisms such as social registries for social safety-nets are reflected in the comparably lower levels of health and nutrition service used by the urban poor. Operationalizing the national registry (National Household Database) developed by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics will help facilitate household level targeting of social safety-net programs. Similarly, providing essential health and nutrition services to women in urban areas, particularly those making a living in the informal sector, have been challenging due to time constrains and a lack of demand. It is therefore important to design outreach programs that cater to vulnerable and hard-to-reach women, especially those engaged in the informal sector such as household help and day laborers.

- Data is key: The current monitoring system, operated by the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), does not cover non-DGHS operated health facilities such as private or NGO-managed clinics. To ensure the continuum of services and data, it is important to bring all entities under a unified system to track progress on key nutrition services and outcomes in urban areas.

As Bangladesh urbanizes rapidly, it is important to address and mitigate these issues before they become insurmountable. Malnutrition is a multidimensional issue requiring multi-sectoral resolutions. Adequately addressing these issues can go a long way, not only terms of the lives lived, and brighter futures realized, but also collectively bring the country to realizing its potential to achieve upper-middle income status by 2041.

Join the Conversation