The robust pace of growth in the South Asia region may be deceptive. Photo: PradeepGaurs / Shutterstock

The robust pace of growth in the South Asia region may be deceptive. Photo: PradeepGaurs / Shutterstock

In South Asia, output growth remains stronger than in other emerging market and developing economies, largely due to strong growth in India. Growth in the rest of the region is picking up, but in most countries it is expected to remain well below pre-pandemic averages, and is insufficient to make progress toward advanced-economy per capita income levels. More than in other emerging market and developing economies, growth is being driven by the public sector. Easing financial market restrictions could help boost growth and private investment in the region.

1. South Asia is growing faster than other regions.

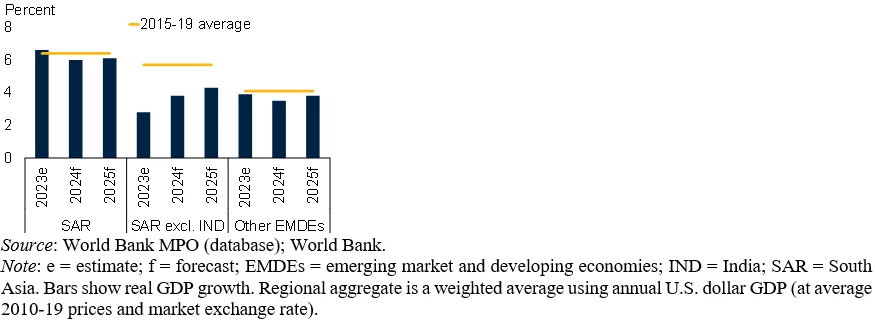

In South Asia, output growth surprised on the upside in 2023 and is projected at 6.0–6.1 percent in 2024–25, stronger than in other emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). This robust pace of growth may be deceptive, however. The region’s above-average growth largely reflects strong growth in India. Many of the underlying vulnerabilities that had caused earlier balance-of-payments pressures remain.

Output growth in South Asia

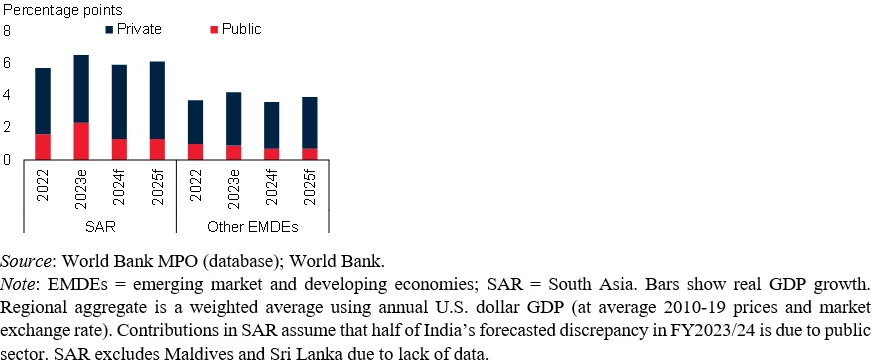

2. Growth is unusually reliant on the public sector.

Growth in the region is more reliant than other EMDEs on the public sector. During 2023–25, government spending in South Asia—including both consumption and investment—is expected to contribute more than twice as much to growth as in other EMDEs. Over the longer term, this may be difficult to sustain given fragile fiscal positions around the region.

Contributions to growth

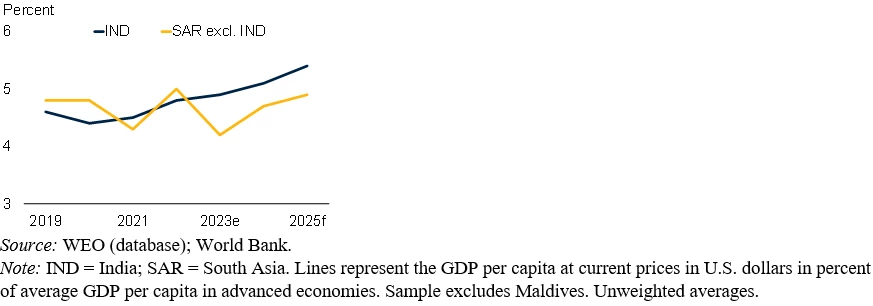

3. Outside India, the region is slow to catch up to advanced-economy per capita incomes.

Much of the strength of output growth in the region is attributable to India, where projected growth is 7.5 percent in FY2023/24 and 6.6 percent in FY2024/25. In the rest of the region, growth this year is expected to remain well below pre-pandemic averages and weaker than in other EMDEs. This pace of growth is not fast enough for significant progress in convergence toward advanced-economy per capita incomes.

Per capita income relative to advanced-economy average

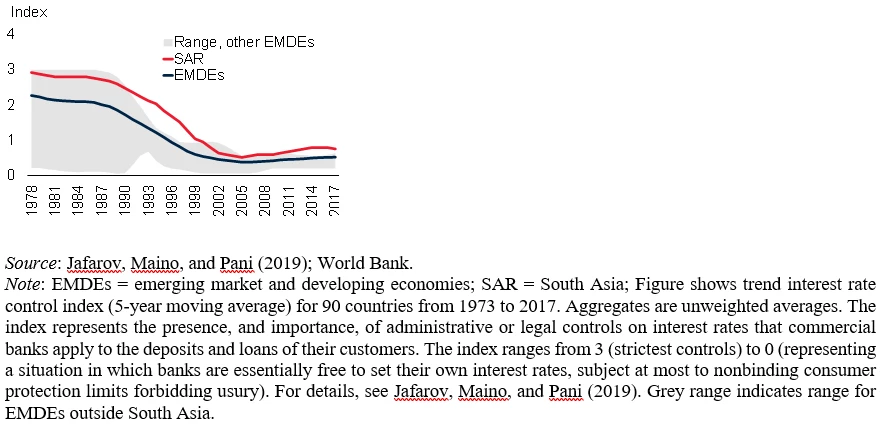

4. Financial systems in the region are more restricted than elsewhere

Financial systems in South Asia are subject to multiple administrative interventions that reduce borrowing costs for favored borrowers, including governments. These include interest rate controls, directed lending, restrictions on entry into the banking sector, and direct government intervention in the financial sector. Controls on interest rates in South Asia, for example, fell sharply during the 1990s but have since been trending up, and by some measures are now greater than in any other EMDE region. Removing some of these distortions could help stimulate firms’ growth and private investment.

Index of interest rate controls

5. South Asia is vulnerable to climate risks.

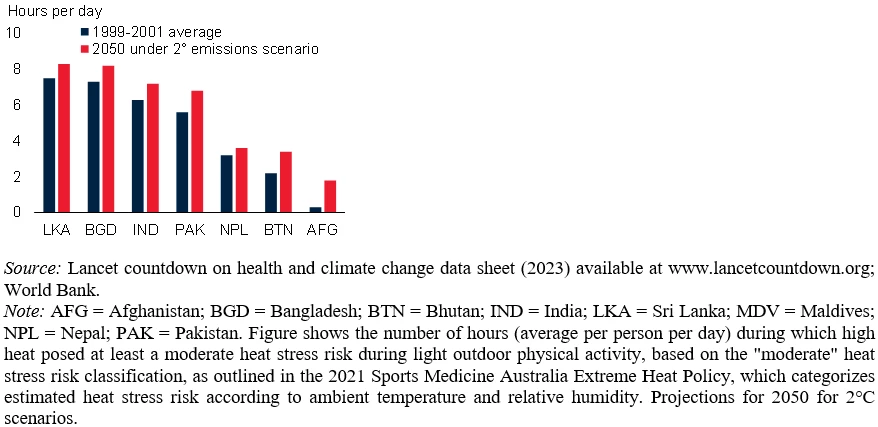

Climate change will have particularly severe consequences for South Asia. Average summer temperatures in the region have already increased by 0.7℃ relative to the 1986–2005 baseline. Heatwaves are particularly damaging for South Asia, because of its already warm average temperature and its large agricultural sector, which accounts for about 40 percent of employment. High temperatures already pose at least a moderate risk of heat stress in much of the region, and periods of unhealthily high temperatures are expected to increase in both duration and intensity in coming decades. Higher temperatures will also make land less productive, cause glaciers to melt, raise sea levels, and increase poverty rates.

Number of hours when it is too hot to work outside

This blog is part of a series on the World Bank's latest South Asia Development Update, Jobs for Resilience.

Join the Conversation