Photo Credit: Shutterstock

Photo Credit: Shutterstock

"My parents stopped my education when I complained about the harassment on the streets and buses enroute to school. They could not always send a male member to escort me to school".

"It is unsafe to take a bus at night because of the long waiting time at a bus stop. No lights and fewer women on the streets while walking back home is very scary and makes me anxious".

“When the office shifted, I had to take the bus to reach the new place of work. I quit the job because of the long waiting hours and the overcrowding on the bus.”

Those quotes and countless others reflect how women’s access to education, jobs, or simply their enjoyment of city life, is hampered by the safety of public transportation systems.

Building on our cooperation with the City of Chennai and its Gender and Policy Lab, we sought to better understand the challenges women face while using public transport in towns and cities and develop a set of prioritized measures for their safer travel. We then expanded this into a Toolkit on Enabling Gender Responsive Urban Mobility and Public Spaces in India.

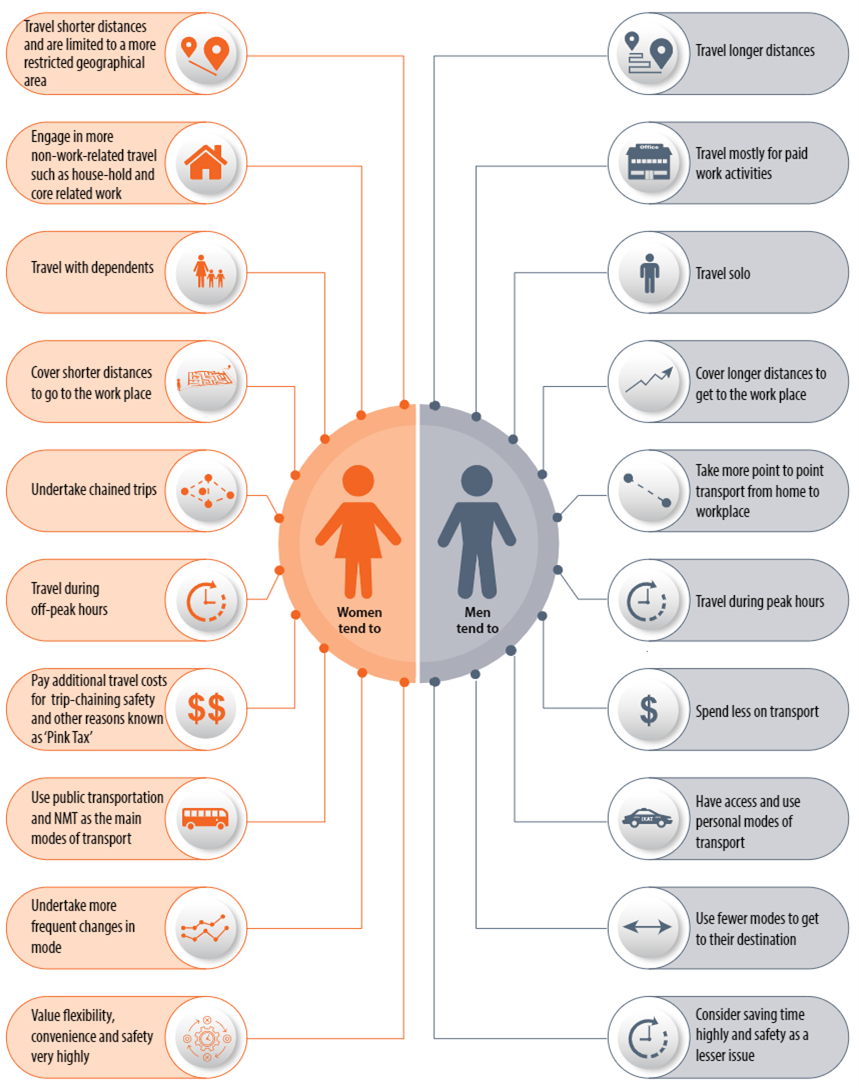

Men and women use public transport differently

Across the world, men and women differ in the way they use public transport. In India, in particular, women tend to travel more at off-peak hours than men, keep within a limited area, often have children in tow , and make several short trips to complete household chores or fetch children from school.

Men, on the other hand, tend to mostly travel for work, often during peak hours, and undertake a single long trip in the morning and evening.

But while transport authorities have long paid heed to the imperatives of the rush hour commute, women’s travel needs are often overlooked.

That is changing now. City governments and public transport authorities are increasingly aware that women’s travel must be made equally safe, convenient and comfortable.

Because women combine several errands in multiple short trips – called trip chaining - they end up paying more for their daily travel. This is often known as the ‘pink tax’ that women pay for ease of mobility in urban areas. A 2019 survey in Delhi showed that while women’s trips were almost 38 percent shorter on average than their male counterparts, men’s average travel costs were 35 percent less than women’s.

Another issue is that public transport, designed with the male commuter in mind, is infrequent at off-peak hours when women make the most trips. As a result, they often end up using informal modes of transport such as autorickshaws, although these modes are more expensive.

Recent survey data across urban India corroborates these trends; it also indicates a concern over women’s travel safety. For instance, in 2021, an online survey across metropolitan areas indicated that almost 56 percent of the women who used public transport reported being sexually harassed.

How travel patterns differ between women and men?

Four critical elements for safer public transport

As city governments, urban local bodies and public transport authorities strive to make public transport more accessible for women, the starting point is basic, but imperative: undertake an on-ground baseline assessment of gender gaps in current transport infrastructure and services. This data-driven approach involves four critical elements:

First, understand gender-based differences in mobility patterns, seeking to answer at least three key questions:

- What are the gender-based differences in mobility patterns in your city, in terms of timing, purpose of travel, distance travelled, trip chaining, trip duration, route-choice and preferred modes?

- What are the key drivers behind these preferences – safety considerations, crowding at particular choke points, cost/affordability considerations, first/last mile connectivity issues, different purposes for travel, or other concerns?

- How can public transport authorities address gender-based differences through gender-responsive infrastructure, services, and differential pricing solutions?

Regularly collecting and analyzing user data covering women, men, and other genders to understand their different mobility needs and patterns is critical to devising evidence-based solutions. It is equally critical to survey non-users and undertake qualitative discussions to understand the factors which deter women from travelling, including individual, social, and cultural factors as outlined in our guidance brief on ‘Unlocking Gender Differences for Designing inclusive and safe public transport systems”.

Second, understand the safety concerns about public transport and public spaces, using both user and non-user surveys to understand the incidence and under-reporting of sexual harassment. Safety audits, a participatory tool that allows women to assess the threat perception of a public space/transport facility, can also provide valuable insights on infrastructure design and use of space.

Since 2015, Delhi has effectively leveraged safety audits to enhance women’s safety. Safetipin (a community-based organization), mapped the entire city at regular intervals and conducted 25,294 safety audits to assess which elements of infrastructure lead to a lack of safety at pavements, bus stops, metro stations and the last mile, as well as at social amenities such as parks, toilets and markets. Street lighting was identified as a major area of focus, and between 2016 to 2019, dark spots in the city reduced from about 7,500 to 2,700.

Third, identify the gender gaps in policies, regulations, guidelines, and legal frameworks. A 2021 gender gap analysis of transport policies and regulations in Chennai showed that amendments would be worthwhile in key state laws and guidelines such as the Tamil Nadu Prohibition of Harassment of Woman Act, 1998; Tamil Nadu Town & Country Planning Act, 1971; and the Tamil Nadu Motor Transport Workers Rules, 1965 to enhance the safety of women commuters as well as of the women employed in the transport sector.

Fourth, assess gaps in institutional capacity to deliver gender-responsive programs. This involves baseline assessments to identify unconscious biases and gaps in technical skills for mainstreaming gender, as well as mapping representation of women and persons of minority genders across job roles in implementing agencies.

The World Bank’s Toolkit on Enabling Gender Responsive Urban Mobility and Public Spaces in India lays out options available, based on an overview of both international and domestic good practices. It provides a detailed “how-to” guide with templates, case studies, and implementation steps to ensure that the mobility systems we build today provide good and safe accessibility for all.

The article benefitted from contributions by Sarah Natasha.

Join the Conversation