The size of a city’s labor market is determined by how far commuters can travel in an hour.

The size of a city’s labor market is determined by how far commuters can travel in an hour.

Where should urban planners focus their efforts? In Dhaka, Bangladesh, and other rapidly growing cities in developing countries, it’s most important to build up job centers and to help people commute to them, so that urban centers are livable and productive and benefit the country as a whole.

Economists say that the size of a city’s labor market is determined by how far commuters can travel in an hour. In Dhaka, 1 hour by car only gets you about 7 kilometers—hardly farther than walking.

Despite being one of the most populous cities in the world, Dhaka’s job opportunities are still clustered in the central business district (including a significant amount of manufacturing) . Road investments have lagged behind population growth for decades, and public transit systems are still under construction.

As a result, workers are forced to compete for a place to live within a one-hour commute. It’s a struggle to find affordable, adequate housing within such a small radius, and many people live in crowded, slum-like conditions.

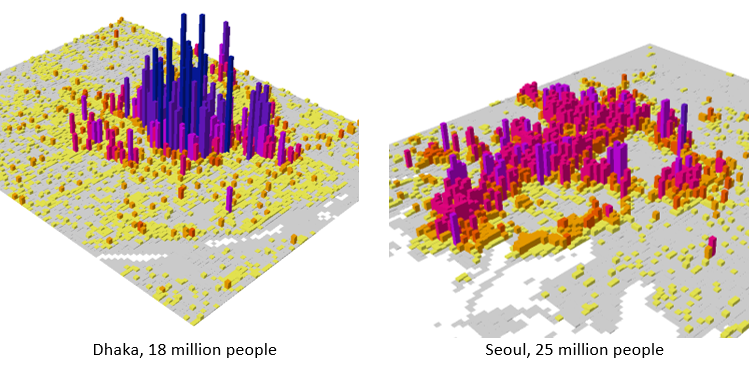

Typically, as cities grow, having most jobs concentrated in a single central business district becomes untenable. Traffic congestion causes firms to decentralize in response to rising commute costs and land prices. New employment centers emerge outside the city center in areas where land is cheaper and there is better access to major highways, as detailed below in the maps of comparable megacities.

The size of a city’s labor market is determined by how far commuters can travel in an hour. In Dhaka, 1 hour by car only gets you about 7 kilometers—hardly farther than walking.

In Seoul, for example, less than one-third of all jobs in the metropolitan region are found in the central business district, and more than half of all new jobs created from 2000 to 2010 were in the suburbs. In Paris and New York, fewer than 30 percent of daily trips are destined for the city center; the rest are between suburbs.

Like any fast-growing city, Dhaka needs additional business districts outside the city center, so the massive labor market converging on the central business district is effectively split into multiple overlapping zones , each covering a one-hour commute to a different job center.

The good news is that some areas outside central Dhaka have started to see rapid growth in firms (especially larger ones). These areas have the potential to be metropolitan-level sub-centers that can be alternative locations for jobs. In seven suburban sub-districts, the number of medium and large textile and apparel firms more than doubled from 2001 to 2013 (this is detailed in the maps below). Similarly, the number of medium and large service firms doubled in the northern metro areas of Savar and Gazipur Sadar, and tripled in Kaliakair. High-value firms like those in finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) increased almost 10—fold in Savar and the eastern area of Rupganj.

4 potential sub-centers

The government has a critical role to play in identifying these potential sub-centers and fostering their development. Based on the observed trends, there are at least four potential clusters across Metro Dhaka that, with the right investments, could emerge as specialized growth poles:

- Savar, Gazipur and Tongi, can become a destination for land-intensive and mature manufacturing industries to scale up, consolidate their value chains, and reduce transportation costs of finished goods. Investments should focus on building communities that serve the everyday needs of low-income workers in the ready-made garment sector and their families: affordable housing, pedestrian mobility, schools for children, and health centers for all people.

- Central Dhaka can focus on revitalizing the heart of the city. There is an opportunity to rehabilitate buildings vacated by industries that have moved out of the city core and improve livability by increasing green spaces and walkability. The area’s high concentration of technical schools, research centers, and new university graduates, it can become a hub for start-ups, creative industries, and knowledge sectors.

- East Dhaka can cultivate the jobs of tomorrow by capitalizing on its endowments of good connectivity to the existing central business district and abundance of undeveloped land. With appropriate long term planning to manage urban expansion and address potential flooding risks, it has the potential to become a center for medium and large firms in high-value sectors like finance and technology. According to a recent World Bank report, East Dhaka could accommodate another 1.5 million residents and boost Dhaka’s GDP per-capita by 15 percent.

- The N8 corridor in the southern fringe of Dhaka can serve as a new gateway for regional trade and logistics. The Padma Bridge, when completed, will link Metro Dhaka to Khulna and Barisal Divisions and ultimately Kolkata. The corridor has the potential to develop new clusters of transport, logistics, and warehousing firms. Local governments along the corridor should plan ahead for rapid population growth and proactively manage the conversion of rural land to urban uses.

The shifting economic landscape around Metro Dhaka offers an important opportunity to foster a more diverse and competitive economy. The government can play a critical role in establishing these sub-centers, through development regulation and strategic public investments.

But there is no one-size-fits all approach. Each sub-center requires a unique package of investments. Those investments must be tailored around the unique features of each sub-center, its economic potential, and its needs for basic infrastructure and service delivery now and in the future. The investments also need to be closely coordinated across sectors like transport, land use and drainage.

The Transforming Metro Dhaka blog series aims to support Bangladesh’s government’s vision of leveraging Dhaka’s economic potential and its contribution to Bangladesh’s goal of reaching upper middle-income status.

Join the Conversation