Local people bathe from municipal water source to keep themselves cool from heat wave on June 10, 2015 in Calcutta, India. Credit: Saikat Paul / Shutterstock.com

Local people bathe from municipal water source to keep themselves cool from heat wave on June 10, 2015 in Calcutta, India. Credit: Saikat Paul / Shutterstock.com

This summer, at 42.6°C, July 25 was the hottest day ever in Paris. Halfway across the globe, Delhi recorded its hottest day at 48°C on June 10.

South Asia, which covers just about three percent of the world’s land area, is home to a quarter of its population.

And sadly, rising temperatures will hit hard the region and its people.

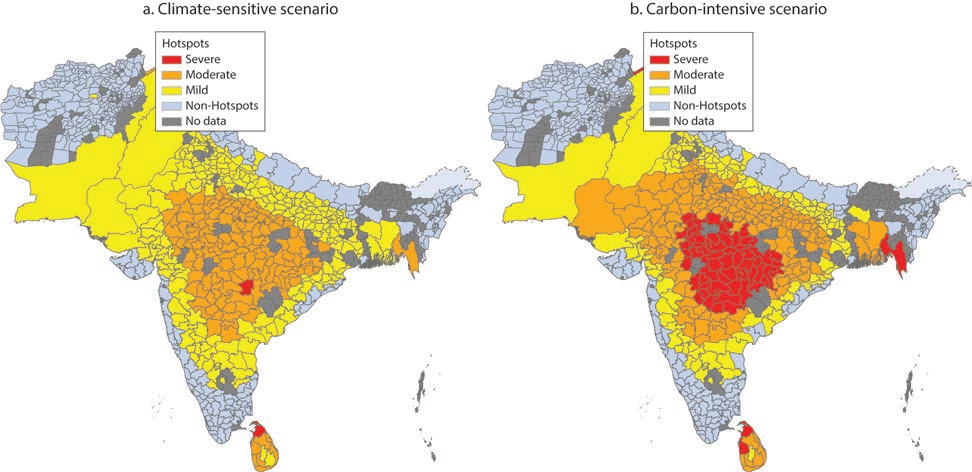

According to the World Bank report, South Asia’s Hotspots annual average temperatures in the region are projected to increase between 1.5 and 3°C by 2050 relative to 1981-2010 , if little or no action is taken to curb carbon emissions.

Around 800 million South Asians—almost half of the region’s population—live in “hotspots” or geographical areas that will experience fewer crop yields, worse health outcomes, and declining productivity. As a result, hard-fought poverty reduction may be reversed.

These hotspots already suffer because of low living standards, poor road connectivity, uneven access to markets, and other development challenges.

Around 800 million South Asians—almost half of the region’s population—live in “hotspots”

Adapting to a changing climate

In coastal areas, sea levels rise, but inland areas suffer the most from rising temperatures.

Similarly, cities and rural areas are vulnerable in their own ways. While the former suffers from urban heat island effects and higher temperatures, the latter experience forced or seasonal migration due to failing crops. Crumbling infrastructure, weak healthcare, and livelihood insecurity occur in both these areas.

Adaptation requires a combination of strategies, which can be implemented at three levels: Individual and household, community and neighborhood, and national and international.

Since the impacts of changing temperatures will be uneven, policies and actions must be tailored to address the specific impacts and needs based on local conditions.

At the individual level, education coupled with behavioral change can improve resilience to extreme heat. Appropriate communication about extreme heat dangers, along with appropriate provision of food, clothing and housing, can reduce heat risk, while home remedies and medical care can effectively treat those who are affected.

As some vulnerable groups may need additional support, communities can work to help each other. Additionally, tree planting or water conservation initiatives can unite government and individuals in curbing heat threats.

Governments can support multinational climate agreements, enforce national building policies, workplace safety standards, labor laws, and public outreach campaigns, and support research. They should also make developing heat action plans for the most vulnerable areas a priority.

As heatwaves intensify, life for many South Asians will change...With appropriate policy and action, it can be managed to ease its impact.

Some adaptation suggestions may counter climate mitigation efforts. Air conditioning, for example, is an effective adaptation measure but also increases carbon emissions. The challenge then is to find win-win solutions. Simply expanding non-fossil fuel-based and efficient energy sources will not suffice. More equitable alternatives to air conditioning need to be explored.

Lastly, bottom-up ethnographic research with affected communities should be conducted to document traditional adaptation measures historically used in the region. These traditional measures should be used along with modern, top-down technological solutions.

Join the Conversation