Vaccine hesitancy is no longer a major constraint. But barriers to last mile service delivery need to be addressed.

Vaccine hesitancy is no longer a major constraint. But barriers to last mile service delivery need to be addressed.

Barriers to last-mile service delivery, not vaccine hesitancy, will be the main challenge to reach the next billion COVID-19 vaccine doses

On January 7th, India reached a remarkable milestone as the 1.5 billionth dose of a COVID-19 vaccine was administered, less than one year since the launch of the national program in January 2021. From the efforts of frontline workers to the roll-out of an innovative technology platform, the vaccine campaign has been an impressive all-round achievement to protect India’s population from the virus. But the arrival of the Omicron variant has been a reminder of the urgency of COVID-19 vaccination efforts worldwide, and so it will be even more important to sustain the momentum achieved so far.

Reaching 2 billion doses and beyond could prove more challenging than the first billion. To help track progress of the ongoing campaign and generate evidence for implementation, some questions on COVID-19 vaccination were added to an ongoing panel survey implemented by the Center for Monitoring the Indian Economy of over 100,000 Indian households across 24 states beginning January 2021. Topics included vaccine hesitancy, coverage rates, and potential barriers to access. Here we present a few highlights based on data collected up to December 31st and offer some reflections on the road ahead.

At the national level, 96% of households with at least one member vaccinated reported that it was received free of charge, highlighting the predominance of public sector delivery. At the state level, there is wide variation in the equity of coverage expansion across both lower-income and higher-income states.

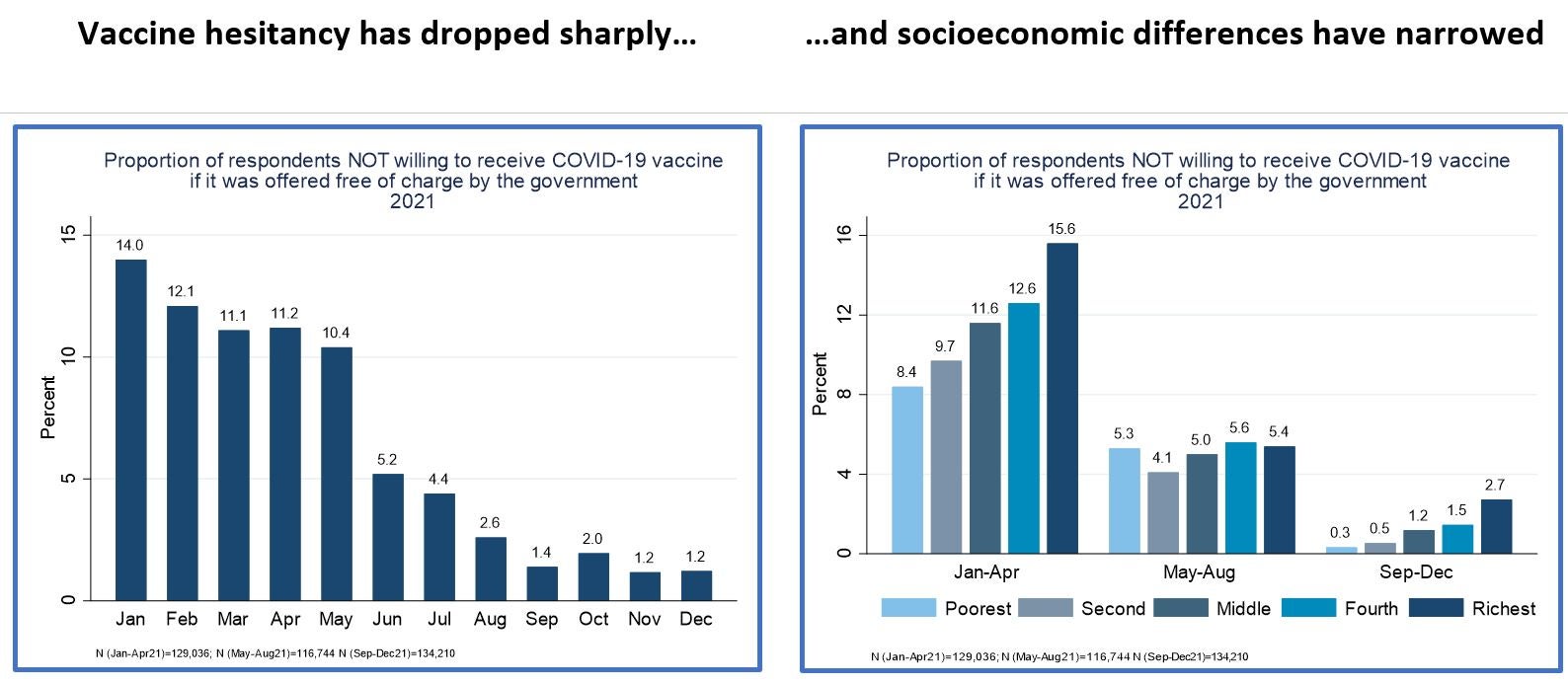

First, the findings suggest that vaccine hesitancy is no longer a major constraint, if indeed it ever was. The share of households stating that they were not willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine if it was offered free of charge by the government declined from 14% in January to less than 2% by December. The sharpest monthly decline followed immediately after the second wave during which COVID-19 cases and deaths had peaked across the country. Moreover, while there were clear socioeconomic differences in vaccine hesitancy at the start of the year – the richest quintile was almost twice as hesitant as the poorest – these differences had disappeared by August, before reappearing late in the year albeit at very low levels. Similarly, while vaccine hesitancy among the Scheduled Tribe population was double the rate of other groups from January to August, this gap had vanished by the end of 2021. Overall, and consistent with previous cross-country studies (see here and here), vaccine hesitancy in India appears to be a smaller problem than elsewhere in the world

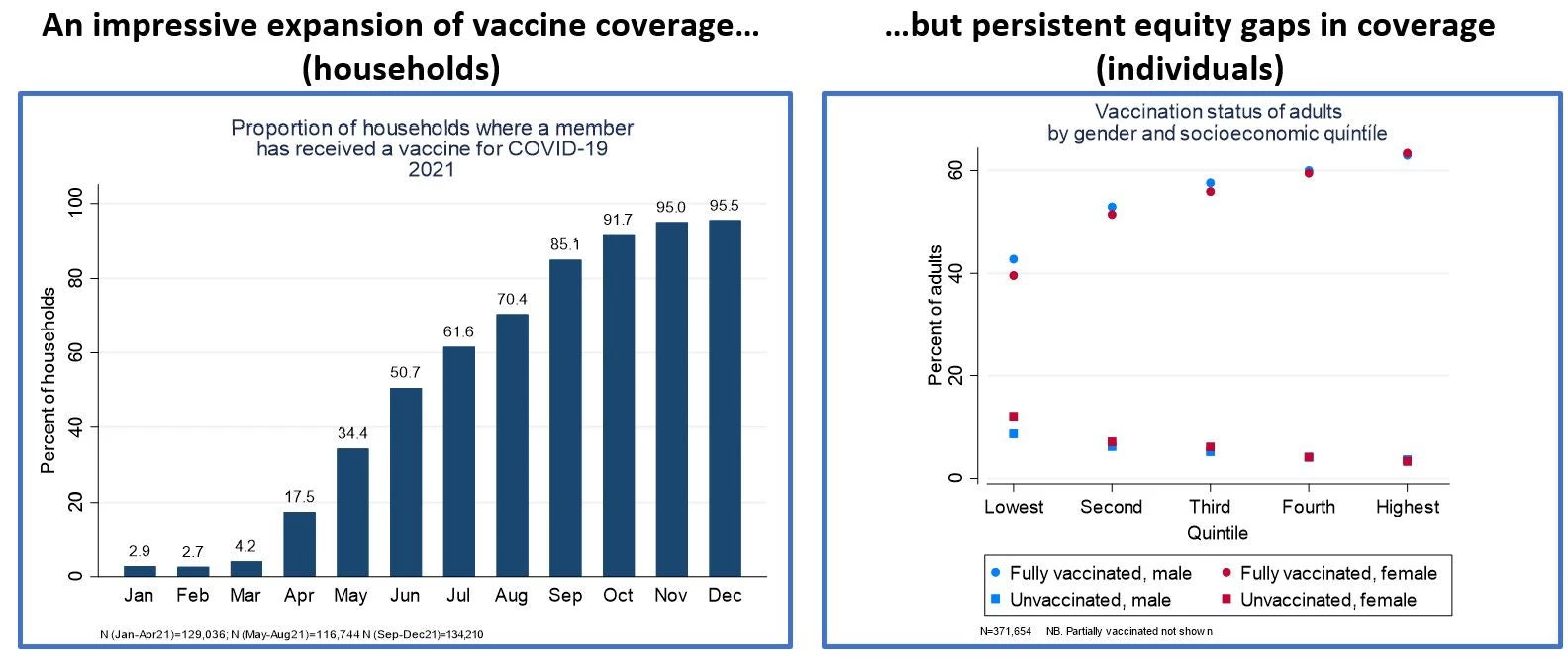

Second, the survey findings highlight the impressive expansion of India’s COVID-19 vaccine campaign but also some gaps that remain. The share of households reporting that at least one member had been vaccinated increased five-fold from 17.5% in April to 95.5% in December. Consistent with administrative data, there are significant differences in vaccination rates across states. At the national level, about 98% of households with at least one member vaccinated reported that it was received free of charge, highlighting the predominance of public sector delivery. At the same time, there is evidence of significant inequalities in vaccine coverage that have persisted since the early stages of roll-out. Only 41% of adults in the lowest quintile are fully vaccinated (two doses), compared to 63% of the highest quintile. At the state level, there is wide variation in the equity of coverage expansion across both lower-income and higher-income states. Interestingly, the socioeconomic gaps in COVID-19 vaccine coverage are almost identical to those observed for routine childhood immunization (% of children aged 12 to 23 months that are fully immunized) as captured by the NFHS-4 survey in 2015-16. There is broad gender equity in vaccine coverage, with only a small gap (1.5 to 3 percentage points for full vaccination) observed in the lower quintiles.

Third, while vaccine hesitancy does not appear to be a major issue, the findings point to other potential barriers to wider vaccine access. There are significant gaps in the share of adults that is fully vaccinated between urban and rural areas (62% vs. 52%) and between those with and without mobile internet access (60% vs. 50%). Although not required, online registration is the most common entry point for vaccine access. And while 94% of all respondents reported that they knew of a specific location where they could avail of a COVID-19 vaccine, a significant jump from mid-year, this was the case among only 64% of the unvaccinated.

India has made extraordinary progress on COVID-19 vaccination in a short period of time. But vaccinating the next billion will require reaching a poorer segment of the population, for whom the main barriers to vaccine access may include knowledge, awareness, proximity and convenience. A greater focus on these aspects of last-mile service delivery may offer the key to bringing the pandemic one step closer to its conclusion.

Revised and updated with data up to end-December (February 18th)

Join the Conversation