nutritious diets in south asia

nutritious diets in south asia

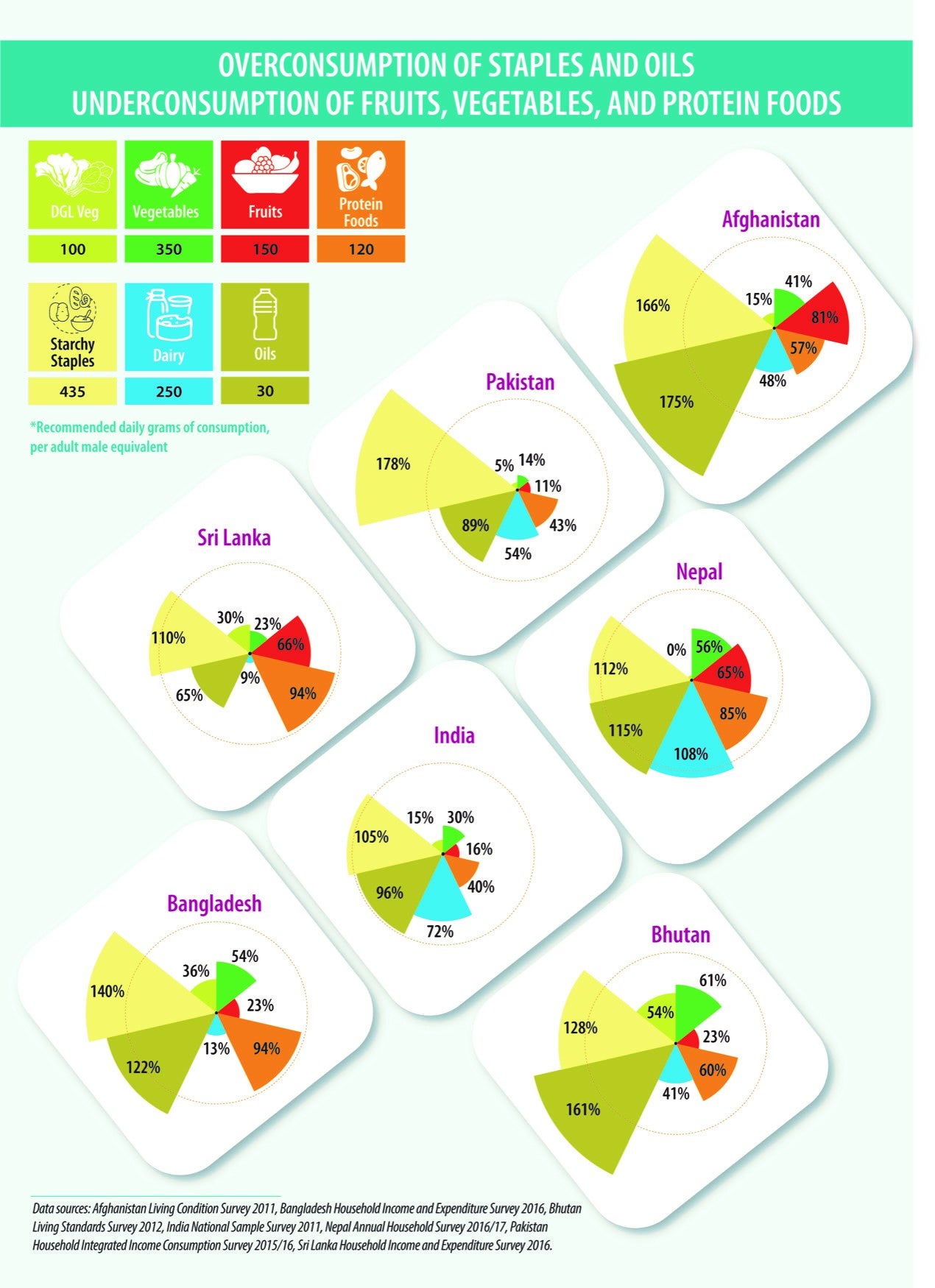

South Asians eat too many cereals and oils and not enough vegetables, fruits, and protein-rich foods. In a new working paper, World Bank researchers analyzed the composition and costs of diets throughout the region, and why people consume less healthy foods even when more nutritious foods are affordable.

It’s not surprising that low-income households find high food prices a barrier to nutritious diets. The minimum cost of a healthy diet ranges from $1.60 per person per day in Bangladesh to $2.90 in Sri Lanka . This cost is out of reach for about half of Bangladeshi households and 3 out of 5 Sri Lankan households.

Vegetables, fruits, and dairy are particularly expensive. For example, in both India and Pakistan, cereals are relatively cheap and account for only about a tenth of the cost of a healthy diet. Vegetables and fruits are more costly and take 40 percent of the cost of a healthy diet in India . Dairy products account for 30 percent of the cost of a healthy diet in Pakistan. Protein-rich foods account for another 15 percent of the cost of a healthy diet in both India and Pakistan.

The lack of affordable diets is worse in certain areas and times of the year. Rural areas have much lower household incomes, which means more rural families than urban families cannot afford a good diet. Backyard gardens are a viable solution to fill some of this gap and can be promoted in combination with boosting incomes and lowering prices. Food price differences are driven mostly by the price of perishable vegetables and fruits, which are harder to transport and store.

Tradition, habit, and lack of information

But even households that can afford nutritious diets may be slow to adopt them because they lack information about healthy foods, or because of traditional customs and preferences. Food preferences and habits are often hard to change as they are built over a long period of time.

Tshering Zangmo, a young mother who works as a hospital receptionist outside Bhutan’s capital, has learned from medical colleagues that a nutritious diet includes an assortment of vegetables and fruits. But Zangmo says she is unable to give up a longtime habit of eating mostly rice every day – even when breastfeeding her two boys, now 1 and 3 years old. “I seldom purchase fruits, legumes, pulses and other healthy food as our family almost always eats rice for all the three meals,” she said. “We have always eaten rice as the main food since childhood. I simply don’t feel full until I eat rice.” Zangmo is typical of many South Asians who eat the same one or two foods each day even when they can afford to buy or grow vegetables needed for a healthy diet.

The Bhutanese mother said she drank changkey, an alcoholic drink made from fermented rice, when breastfeeding her children. “It is in our culture to drink changkey as we believe that it will help mothers lactate better, and also help the baby sleep well,” she says.

The right interventions, investments, and policies

South Asians can improve their diets with interventions, investments, and policy changes. Better diets are especially important for children as their brains and bodies develop. A varied and nutritious diet can help prevent stunted growth in children, reducing lifetime health costs and improving productivity.

Interventions should include communications campaigns to encourage behavior change and explain the benefits of better diets, similar to a successful campaign by women’s self-help groups in Bihar, India which promoted both better sanitation and diets. Interventions can also include social protection and livelihood programs to increase incomes and encourage households to plant a small garden with nutritious foods, especially in rural areas.

Also important are investments in transport and storage infrastructure so markets can stock nutritious food at lower prices year-round, especially in remote areas. Such infrastructure builds stronger markets for everyone, including farmers. Equally important are innovative solutions, similar to Bangladesh call centers created during the pandemic. The call centers match farmers with suppliers of seeds and inputs, and with crop buyers for smooth functioning of the food supply chain.

Finally, government policies need to consider if the current focus on grain subsidies and price controls should be modified to make a better diet more affordable. Policies that encourage farmers to grow diversified crops can make more foods available at affordable prices for consumers. Support for agricultural innovations and transparency could have a big impact on healthy diets. For example, Punjab’s policy reforms to streamline agricultural marketing channels and reduce fees are paving the way for more affordable diets.

We need to continue to rethink interventions, investments, and policies for better diets — now more than ever. The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare weaknesses in the current food chain infrastructure and nutrition. Reimagining diets will lead to healthier people and a healthier planet .

This research was funded in part by the South Asia Food and Nutrition Security Initiative, which supported cutting-edge research on the intersection between food and nutrition in the region.

Join the Conversation