Children at a school in North Macedonia sit around their teacher, who is reading a story book to them

Children at a school in North Macedonia sit around their teacher, who is reading a story book to them

The release earlier this month of the 2021 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) data provides a critical opportunity to learn how COVID-19 impacted students’ reading ability across the advanced and emerging economies of Europe and Central Asia (ECA). Led by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), this data collected during the fall of 2021 measured fourth graders’ capacity to read.

In ECA, the PIRLS sample covers 35 out of 58 countries, 26 of which we have 2016 data for comparison.

Here are five key takeaways from reviewing this data:

1. Students in late primary schooling from high-income ECA countries, typically benefiting from larger per student investments in basic education, continued to demonstrate higher reading comprehension. However, on average, reading comprehension across the region tends to be better than in other regions of the world, including countries at the same level of development.

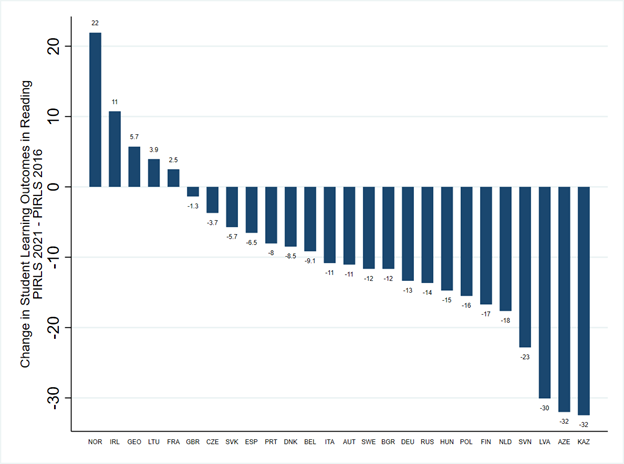

2. Between 2016 and 2021, ECA countries experienced larger declines in reading comprehension than non-ECA countries. This was commonplace across high- and middle-income countries. According to Figure 2, 21 of 26 ECA countries with PIRLS 2016 and 2021 data experienced a decline in reading outcomes. Of these, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan report the largest declines in reading comprehension during this period of more than 30 PIRLS points, equivalent to a loss of around a full year of schooling. Such losses have pushed an increasing share of students across ECA below a minimum reading proficiency, i.e., unable to read and comprehend a grade-level text. This trend stands in contrast with past improvements in outcomes before 2016, especially for middle-income countries.

3. COVID-induced school closures seem to have impacted student learning in ECA, with exceptions. The figure below depicts a strong positive correlation between the number of days of mandated school closures and the decline in average student learning at the country level. The longer schools were closed, the larger the decline. Countries like Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Latvia that experienced the largest declines experienced the longest duration of school closures—around 250 days of full or partial school closures.

However, countries like Lithuania and Georgia avoided learning losses and improved students’ learning outcomes despite long school closures, suggesting a deeper analysis is necessary. Although the changes between 2016 and 2021 cannot be fully attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, it likely played a major role. Students assessed by PIRLS were already in grades two and three when the pandemic struck, a critical period to establish the foundations on how to read. Moreover, when the data was collected, students had been without in-person schooling for several months.

4) Between 2016 and 2021, within-country inequality in children’s reading ability across families of different socio-economic backgrounds increased across most ECA countries. For example, in 2021 students in Hungary and Bulgaria belonging to the poorest quintile perform 130 and 122 PIRLS points behind their peers belonging to the richest quintile, which is roughly equivalent to four years of schooling. For 15 ECA countries, differences increased in 2021 compared to the levels observed in 2016. Sweden and Netherlands were among the countries where these inequalities increased more. There the average reading comprehension for children in the richest income quintile improved between 2016 and 2021, while the average reading comprehension for children in families of the poorest quintile declined over the same period.

5) Families’ engagement and resource allocation in student learning through COVID-19 was significant but varied across countries. Roughly 80% of parents across ECA perceived some impact of the pandemic on student learning. On average, more than half of families in ECA countries provided books, digital devices, digital learning materials, and remote tutoring for their children. Moving forward, policymakers should try to leverage on existing parental engagement in the learning recovery of their children and try to foster it further, especially for families from vulnerable populations.

Learning losses over the last five years across European and Central Asian economies are real and will impact the region’s economic and social development if not reversed by active policy intervention. The World Bank, together with partners, has developed a Reach/Assess/Prioritize/Increase/Develop (RAPID) framework that countries could operationalize to change the trajectory of student learning, especially for the COVID-19-affected generation and vulnerable students. With well-targeted actions, the learning losses registered by PIRLS can be reverted, and lost learning recovered across ECA.

A deeper analysis of the initial PIRLS 2021 data is provided in the following note.

Join the Conversation