İstanbul’un en önemli sembollerinden olan meşhur Boğaziçi Köprüsünde, Türkiye’de COVID-19 salgınının yayılmasını kontrol altına almaya yönelik sıkı kısıtlama önlemlerinin yürürlüğe girmesi ile birlikte trafik neredeyse tamamen durdu.

İstanbul’un en önemli sembollerinden olan meşhur Boğaziçi Köprüsünde, Türkiye’de COVID-19 salgınının yayılmasını kontrol altına almaya yönelik sıkı kısıtlama önlemlerinin yürürlüğe girmesi ile birlikte trafik neredeyse tamamen durdu.

COVID-19 is the largest public health and economic crisis to hit the world in nearly a century. The crisis has also revealed deep inequalities, with the poor bearing a disproportionately higher burden.

Take the case of Turkey, where poverty was on a downward trend until the 2018 currency crisis and inequality has been on the rise in recent years. Recent analysis, using micro data on job losses and household consumption to gauge the impact of the pandemic, suggests that the crisis may create 1.6 million new poor, setting back poverty reduction gains by three years.

To contain the spread of infections when the pandemic first struck Turkey in March last year, the government imposed strict measures that reduced human mobility by 70-80%. As a result, economic activity plunged, shrinking the Turkish economy by 9.9% in the second quarter of 2020. This, together with massive disruptions in global trade and tourism, led to the destruction of 2.6 million jobs (9.2% of total employment) in a matter of weeks.

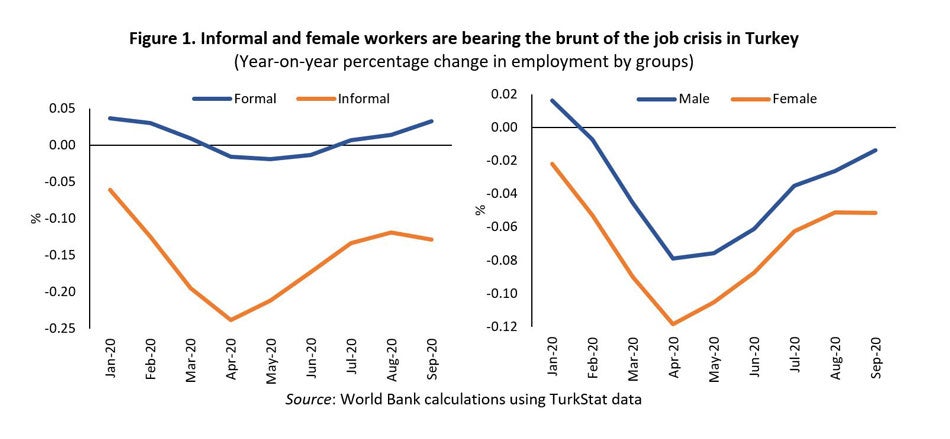

But, a closer look at the numbers shows significant variability on the effects of the pandemic on the different segments of the population. Figure 1 shows that the bulk of the job cuts impacted informal workers, the lower-skilled, as well as women. Female workers, for instance, were three times more likely to become unemployed than their male counterparts given their high concentration in activities highly affected by the containment measures such as hospitality, food, tourism and other services.

All in all, in Turkey, the poor and the vulnerable (those above the poverty line but with high levels of economic insecurity), representing the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution, account for 6 out of 10 jobs that vanished during the crisis (Figure 2). In stark contrast, the better off were much less likely to stop working and the top decile of the income distribution even enjoyed net job gains.

At the same time, at the peak of the crisis, 4 million people (12.3% of employment) either opted out or decided not to enter the labor market due to weak job prospects or school closures. This setback is particularly worrisome for women, whose labor force participation declined by 5.2 percentage points to 29.2% between April 2019 and April 2020.

Bringing them back to the market may prove challenging. It took Turkey almost a decade of robust and stable growth to lift female labor force participation by a similar rate. In addition to the losses in income from the crisis, high inflation – largely fueled by monetary and credit expansion policies to stimulate the economy – further squeezed the already strained purchasing power of poor households.

In the second half of 2020, the prices of basic goods and services with a high share in the typical consumption basket of low-income families recorded significant increases: unprocessed foods rose by 19.8%, bread and cereals by 16.3% and transport by 14.7%. The overall Consumer Price Index rose by 12.6%.

Unequal recovery

The Turkish economy rebounded strongly in the third quarter of 2020 as the first wave of COVID-19 subsided, the stimulus package kicked in and restrictions on mobility were eased. In fact, as of September 2020, 72% of the jobs lost (1.9 million) had been re-gained. But the job recovery has also been unequal, benefitting mainly formal and skilled workers.

As of September, more than half a million women remained out of the labor market and another half a million who were unemployed had not recovered their jobs. These disparities are not exclusive to Turkey. Overall, data from developing countries and advanced economies show that the labor market recession for high wage workers has been both shorter and milder (for instance, lasting only three months in the United States), whereas it is still weighing down heavily on workers from the bottom of the income distribution.

For a robust and sustainable recovery, many voices are calling for a renewed emphasis on making economies greener and knowledge- and technology-based in the post-pandemic era. This crisis also offers a great opportunity to tackle another long-standing critical challenge that is being exposed and further exacerbated by COVID-19: rising inequality.

The increase in poverty in Turkey could have been three times higher had the government not acted swiftly and decisively, implementing a number of mitigation policies such as increased social transfers, unemployment insurance benefits and unpaid leave subsidies. The Turkish government’s pandemic-mitigation efforts have been laudable and effective but addressing the growing inequalities will require extra policy action.

Among the most immediate challenges are to protect the livelihoods and human capital of disadvantaged households. With many individuals unable to find a job or work for enough hours, guaranteeing a minimum level of consumption requires extending the length and adequacy of benefits from the ongoing social assistance emergency support.

Priority should be given to urban self-employed workers – about a third of total employment and comprised mostly of unskilled workers in high risk sectors – who are not covered by wage-support mechanisms that are part of the crisis response.

The impact of the crisis on education is a serious concern. According to the World Bank’s Fall 2020 Economic Update for Europe and Central Asia, close to one learning-adjusted year of schooling will be wiped out in the region due to school closures. Most of these losses will be borne by children from low-income families weighed down by the digital divide.

Only 6% of poor families in Turkey own a computer and 2 out of three poor households lack internet access. In addition to current strategies to strengthen distance learning, Turkey will have to step up investments in early age education and learning support to ease the transition back to school, close learning gaps of poor children with their peers and reduce the risk of having massive dropouts.

Finally, the conditions created by the pandemic will accelerate pre-existing structural changes in the labor market, such as the shift to work from home and automation. These forces will weaken the demand for some types of labor, particularly unskilled workers. In Turkey, about 10 percent of jobs can be performed from home, but the overwhelming majority of them are in sectors and occupations only suitable for skilled workers. Upskilling, training and other active labor interventions, many of which are currently implemented by ISKUR, the Turkish Employment Agency, will have to be sustained and deepened in a post-pandemic economy to avoid those gaps from widening further.

It is still not too late to change the course of global and regional inequality and make the recovery not only robust and sustainable but also equitable. It is time now more than ever for trust, solidarity and above all greater inclusiveness.

Join the Conversation