I attended school in the 1990s, on the outskirts of Minsk. Back then, many people in Belarus were experiencing economic hardship, and my family was no exception. As such, school played a major role in my young life.

In third grade, I discovered a world globe in a cabinet in our geography classroom. I was so curious about it, my teacher allowed me to take the globe home for a week, during which time I eagerly learned about things such as continents, seas, deserts, rivers and mountains. Soon, I could quickly point out places like Mount Everest and the Mariana Trench.

That experience was an early lesson for me about the benefits of school and the opportunities it provides for children to access new and interesting information.

Today, as a young parent, I think about the learning experience my own child will get in school and how it will prepare her for the future.

I have many questions, including: how to get young kids really interested in topics such as physics and chemistry? Are textbooks enough to stimulate curiosity in a particular subject, or should other means, including digital tools, be made available? Is there a role for Virtual Reality in the classroom, or for 3D printers? Do children learn better when doing project research and working in small groups?

To find out more about the quality of education in Belarus, I consulted the OECD’s PISA study, in which Belarus took part for the first time in 2018. PISA can tell us a lot about our country’s education system and its learning outcomes.

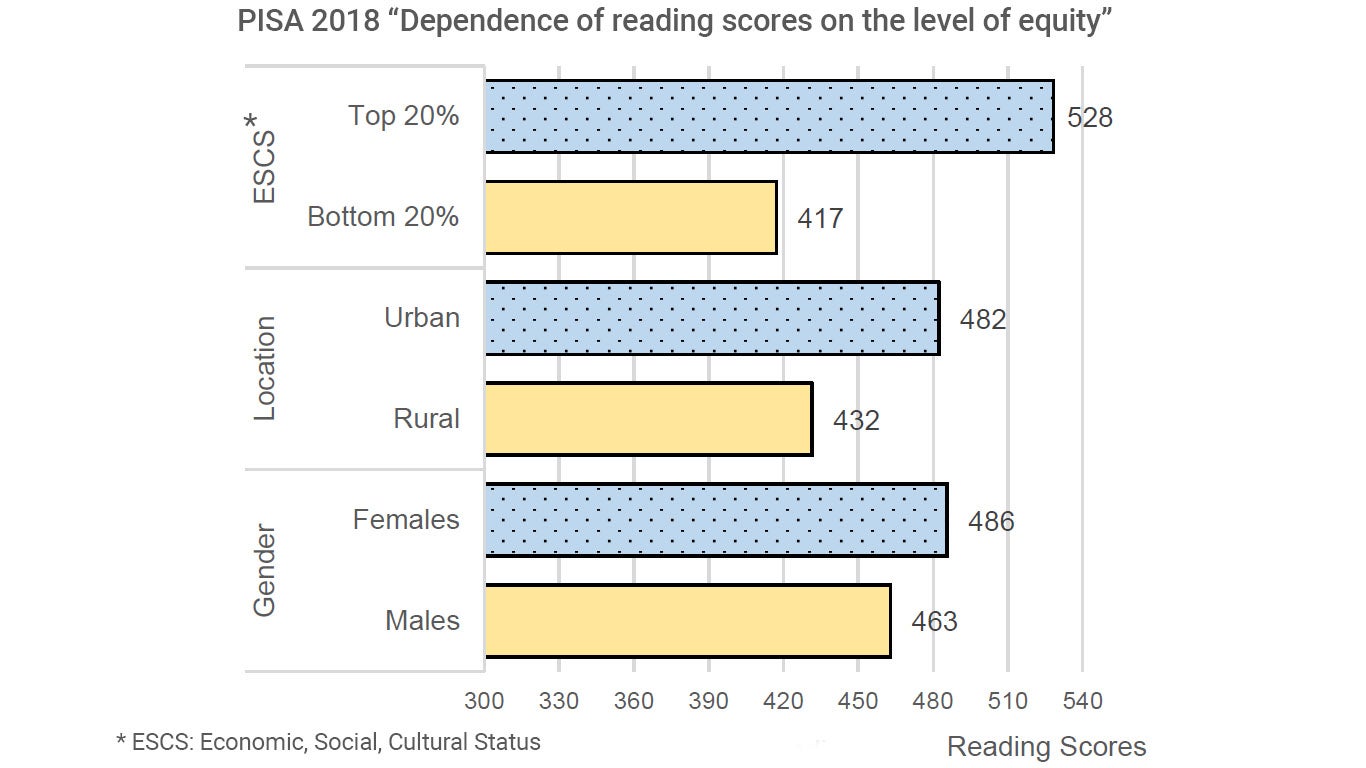

For example, Belarus’ PISA results indicate a rather significant difference in the performance of children from cities and those from small towns and villages in Belarus. In fact, the gap is about 40 points, equivalent to about one year of study. An even greater difference is found between the results of children from the poorest families and those from the wealthiest.

Improving the education outcomes of children left behind should be a priority. Numerous studies confirm that investments in children at an early age help reduce inequality throughout their lives and generate higher income returns as adults. The results of the PISA test in “reading” underscore the benefits of early investment: the highest number of points were scored by children who went to kindergarten from the age of 2-3 years.

Belarus has faced a steady decline in the number of school-age children over the past two decades. As such, the government is taking important steps to improve the learning environment, including through rehabilitation of school facilities and provision of essential laboratory equipment for physics, chemistry, biology, and information technology.

As part of this national effort, the Belarus Education Modernization Project, which is implemented with support from the World Bank, aims to improve access to quality learning in more than 280 general secondary schools, and also strengthen student assessment and education management information systems. An estimated 65,000 schoolchildren from small towns and villages across Belarus will benefit from this project.

Last January, I visited a school in the small town of Voronovo, which has just over 6,000 residents. The school had recently undergone rehabilitation work. More than 1,000 children attend this school, and those with whom I had a chance to meet, spoke about it with unconcealed pride.

Thanks to the project, there will be more and more such schools in Belarus, and classrooms filled with student innovation, training, communication and teamwork. Such investments will pay off in the long-term, both for the individual and for our society.

In a year and a half, my daughter will start primary school. I truly hope she will find the learning environment highly stimulating and interesting, as I once did. I tell her this, as she sits on my lap and we spin the globe together.

___________________________

RELATED

BLOG: Why PISA is an important milestone for education in Belarus (June 14, 2018)

Join the Conversation