World flags displayed in a row

World flags displayed in a row

Reflections from the 2021 Governance Forum.

The role of institutions has become one of the most popular research areas in development economics over the last 30 years. However, despite the general recognition that “institutions matter” for development, the nature of the relationship is still debated and contested. Interesting questions remain unresolved:

- What specific set of institutions are optimal or desirable for economic growth?

- Do countries need to build strong institutions first and growth will follow, or do they evolve together?

The experience of several countries (including China, Vietnam, and Cambodia among others) shows that growth was initially stimulated by a small number of institutional and policy changes, despite an otherwise unfavorable governance environment (Rodrik 2007). If anything, history highlights that growth acceleration can and did happen under a variety of institutional trajectories. What made the difference was the ability of institutions to adapt to the changing economic context (Fukuyama 2014), empowering local actors to find innovative solutions for evolving problems (Yuen Yuen Ang 2016).

The topic was debated at the 2021 Governance Forum with MIT’s economics Professor Daron Acemoglu and Andres Velasco, Dean at the School of Public Policy at the London School of Economics. A few take-aways from this inspiring debate:

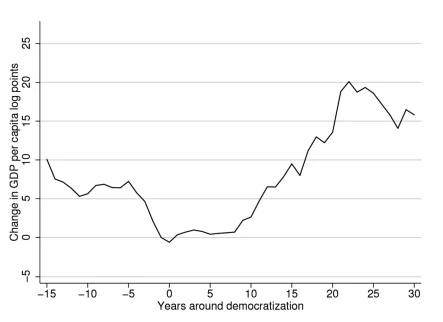

Institutions are as good as the capacity of the State that upholds them. Institutions are embedded in a country’s social context, which affects the way they function as well as their effect on economic outcomes . For instance, research by Acemoglu et al 2019 suggests that, on average, democratizations increase GDP per capita by about 20 percent in the long run (Figure 1 Below). However, that does not mean that one can just introduce elections and hope to get the observed average boost-effect. State capacity – shaped by the incentives, beliefs and professional norms shared among state personnel - is crucial to explain differences in institutional performance and policy effectiveness.

Figure 1: GDP Per Capita before and after Democratization

Not all institutions are created equal, and certain institutions matter more than others. Researchers have long tried to identify ‘prime movers’, institutions which have particular power to change others. This is not an easy task. Institutional strengthening is a long-term process that unfolds over decades, if not centuries . Yet, policy makers can still make a difference and look for ‘smart’ institutional reforms in the short term. According to Prof. Velasco, such efforts should look for low-hanging fruits, quick wins and shortcuts, unleashing the process of further institutional reforms. The case of budget institutions - including, among others, fiscal responsibility laws - illustrates this point. Countries like Peru and Chile were able to avoid painful fiscal austerity measures and effectively manage public debt during times of crises, thanks to solid budget institutions established during period of economic growth.

Politics matters. Institutional reforms may be stymied by vested interests or the inability of key interest groups to reach an agreement on policy reforms, leading many countries to get stuck in the ‘middle-income trap’. As shown in the WDR2017, middle-income countries may be particularly susceptible to these political economy challenges, as the case of tax reforms illustrates. As countries get richer and economies become more complex, the State also grows. However, in many countries tax revenue over GDP is surprisingly low given per-capita income, undermining state capacity to function and meet citizens growing demands. Powerful economic interests block the very institutional reforms needed to mobilize domestic revenues, such as taxation of financial capital, real estates, and agriculture assets.

In the post-COVID world, we need an institutional revolution to develop the ‘right kind’ of technologies for better economic and social outcomes. The COVID-19 crisis has accelerated pre-existing challenges that undermine the quest for growth and shared prosperity. In the United States, for example, inequality has steadily increased over the past four decades, and economic growth has benefited mostly those with post-graduate degrees and specialized skills. The underlying reason is a social and economic equilibrium where all the efforts are going toward automating work. Across the world, recent technological change has been biased towards automation, with insufficient focus on creating new tasks where human labor can be productively employed (Acemoblu and Restrepo 2019). If nothing changes, this “distorted path” will undermine developing nations’ efforts to prosper, let alone go through the growth spurts that economists would like to observe. However, societies, via government policies and regulations, decide how technology is used, its direction of change and who benefits from it.

So, what can be done to build a better future? Again, the solution is an institutional one. As Prof. Acemoglu pointed out, a new institutional framework is needed for better regulations of technology and social safety net for the disruption created by automation. At the international level, this might require an inclusive and transparent governance model where emerging economies can have their voices heard, and actively participate where decisions on the future direction of technologies are taken.

Join the Conversation