A characteristic weakness of a young democracy, such as Ghana, is the electoral fiscal cycle it tends to generate. The literature has established firmly that more nascent democracies exhibit larger fiscal deficits and looser monetary policies around election time. That these cycles are absent in more evolved democracies with higher levels of transparency and where polarization is lower, as well as in very poor states which lack the capacity to expand fiscal and monetary variables at will or whose real electoral action occurs in the informal spheres of activity.

While there are many positive outcomes associated with democracy – most notably, the stability and security conferred by legitimacy – growth does not seem to be among them. Generally, democracies have not outperformed autocracies in terms of economic growth, partly perhaps, because young democracies have to traverse a difficult space of ”learning by trial and error” and institutional building on the long voyage from autocracy to well-functioning democracy.

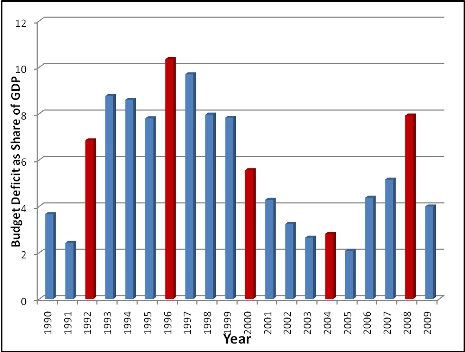

While Ghana is leading the way in Africa on the path to mature democracy, its competitive politics and relatively young institutions- and resultant electoral fiscal cycle – remain a constraint to faster growth. Since the resumption of democracy in 1992, there has been an exceptionally large fiscal deficit nearly each election year (see graph, election years are in red), followed by a painful fiscal adjustment afterwards, with those in 1992, 1996, and 2008 proving especially destabilizing. This history of macro instability has pushed up inflation and the real interest rate, which along with exchange rate movements have taxed the poor and reduced private investment below its potential.

The good news and the reason for my optimism is that this problem has now become evident in Ghana. The last election in 2008 was won by the party in opposition in spite of massive spending by the ruling party. Since then, the nation has seen vigorous debates on how to address this issue head-on.

Progress seems to be driven by two important developments. First, each of the two main parties has now fully realized and accepted that no election will be their last. This increasingly pushes them to take a longer term view, knowing that they will eventually be back in power even if they do not win the next election. Keeping the economic house in order is increasingly perceived as more important than winning at all costs – indeed, trying to win at all cost is starting to be seen as a flaw by important parts of the electorate. This leads to the second factor, which is that the electorate is becoming savvier. In particular, the private sector has emerged as a key swing vote against parties willing to sacrifice the nation’s investment climate for reelection. Furthermore, organized groups of citizens are also demanding accountability from government – as reflected in civil society advocacy for responsible oil revenue management laws or independent budget analysis among many other examples.

The improvements being sought are of three types. First, there is a discussion, most active presently in the context of a constitutional review, to reduce the phenomenon of winner takes all. Currently for example, the president appoints all district heads and all public boards in the country (thousands of people). This creates enormous incentives to win at all costs. There are now serious considerations to curtail this presidential prerogative.

The second dimension involves transparency and timely access to information. Voters have been learning from experience not to trust all that they see around election time, but unless they have access to data, it is difficult to disentangle effort, luck, and overspending. Ghana has developed a draft freedom of information act, which now sits before Parliament for approval. Important elements of this drive are that it is led by a dynamic civil society, and that it has focused from the outset on implementation challenges.

Finally, Ghana is starting to explore how it can tie the hands of its politicians to improve fiscal management. Parties have more incentives to overspend when the opposition campaigns on a platform of high spending. This ends up hurting the country. In Ghana, there is a tradition of inter-party election engagement rules which could be broadened to the core principles of good economic governance that both parties should stick to, which would include elements of fiscal responsibility. Some voices insist that legislation, or even a constitutional amendment would do a better job. The discussion is however still at an early stage, but the size of the deficit during the next general elections year in 2012 is already the subject of intense discussions.

While Institutional development is a long term challenge, with continued momentum, Ghana can and must continue to lead the way forward in Africa. Only then will she be able to sustain the high growth rates that her population wishes for and deserves.

Photocredit: bbcworldservice

Join the Conversation