Adobe

Adobe

Justice systems in countries affected by fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV) face multiple challenges such as lack of independence, corruption, improper government influence, institutional and administrative problems, inadequate access, and inefficiency. In a recent report, we identify seven steps on how to increase access to justice in these settings and offer insights into the process and sequencing of reforms designed to strengthen the rule of law.

- Analyze the level of fragility: Countries with ongoing conflicts and no infrastructure face a different set of challenges in their justice systems than countries with no conflict but some level of institutional fragility. Therefore, it is important to prioritize resources based on context analysis in order for reform processes to succeed.

- Identify existing justice actors: In many Fragile and Conflict-affected Settings (FCS), people rely on local traditional or religious leaders to help them resolve disputes. In the African continent, for instance, 71% of the population living in FCS resort to them . These non-state actors often work alongside the formal courts but are perceived as accessible, quicker, relatively inexpensive, and culturally sensitive. Mapping local power structures is necessary to put people at the center of justice, respond to their legal needs, and have more impactful interventions.

- Develop institutions harmoniously with existing dispute-resolution mechanisms: Local, traditional, customary, and religious systems fill an important justice gap in FCS, especially for people in rural areas or of lesser means. State institutions can leverage non-state forums to expand access to justice while addressing potential risks, including discrimination and human rights abuses.

- Prioritize transitional justice in the immediate aftermath of the conflict: The sequencing of reforms should guarantee victims’ rights to truth, reconciliation, reparation, and non-recurrence of violence. Transitional justice mechanisms can address past violations and create a path toward reconstruction and building institutions. Laying out a robust post-conflict legal and institutional foundation can considerably enhance the credibility of the justice system.

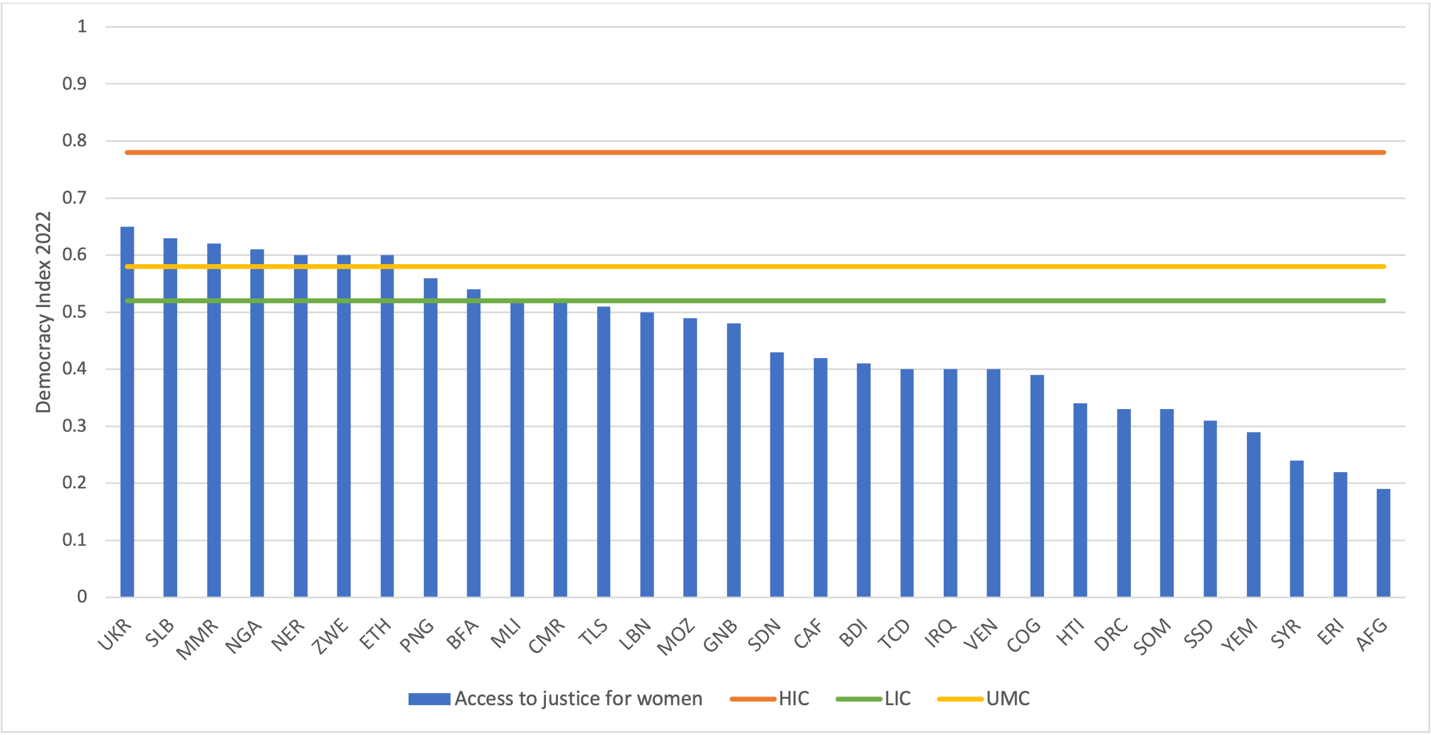

- Expand services to underserved communities: After setting up transitional justice mechanisms, governments in FCS can expand services to rural communities, women, and minorities. People in areas with inadequate roads or public transport may not be able to access services since resources are prioritized for high-density areas. Legal and practical barriers affecting women should also be addressed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Access to Justice for Women is Lower in FCS than in Lower-Income Countries on Average

Source: Global State of Democracy Index, 2022.

Source: Global State of Democracy Index, 2022.

Note: The score ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 represents the strongest democracy. Includes countries from the 2023 FCS list for which data are available in the Global State of Democracy Index. AFG = Afghanistan, BDI = Burundi, BFA = Burkina Faso, CAF = Central African Republic, CMR = Cameroon, COG = Congo, DRC = Democratic Republic of Congo, ERI = Eritrea, ETH = Ethiopia, GNB = Guinea-Bissau, HIC = high-income countries, HTI = Haiti, IRQ = Iraq, LBN = Lebanon, LIC = low-income countries, MIC = middle-income countries, MLI = Mali, MMR = Myanmar, MOZ = Mozambique, NER = Niger, NGA = Nigeria, PNG = Papua New Guinea, SDN = Sudan, SLB = Solomon Islands, SOM = Somalia, SSD = South Sudan, SYR = Syrian Arab Republic, TCD = Chad, TLS = Timor-Leste, UKR = Ukraine, UMC = upper middle-income countries, VEN = Venezuela, YEM = Yemen, ZWE = Zimbabwe.

- Ensure efficiency in managing the increased demand for judicial services: Expanding judicial services creates demand, which can strain already fragile or recently established justice institutions. Governments in FCS can introduce case management tools and ICT solutions to monitor the efficiency of the courts and reorient financial and human resources as needed to face potential backlogs.

- Focus on quality: Once governments resolve urgent conflict-related needs and improve access and efficiency, they can ensure that court decisions conform with legal requirements and users’ expectations, through constitutional review processes, monitoring of appeal and reversal rates, and increasing subject-matter specialization. Specialization can help judges become more proficient in case disposition and cut down on delays and backlogs.

The potential impact of leveraging these reforms is immense. By 2030, more than half of the world’s extreme poor will live in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Settings . Establishing legitimate and effective institutions can help them transition out of conflict and fragility. In turn, sustainable socio-economic development, and the maintenance of the rule of law depend on the health of justice institutions.

Editor’s note: This blog post is part of a series on Justice and Development in the Global Program on Justice and the Rule of Law, which is supported by the State and Peacebuilding Fund.

About the State and Peacebuilding Fund (SPF):

The SPF, a global multi-donor fund administered by the World Bank, supports programs that address the drivers and impacts of fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV) and strengthen the resilience of countries and affected populations, communities, and institutions. The SPF is supported by: Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.

Follow this link to learn more about the SPF.

Join the Conversation