On May 6 and 7, 2014, Indonesia will host the Regional Open Government Partnership (OGP) conference in Bali, a milestone in its chairpersonship of the OGP. As evidenced by the rallying themes of innovation, openness and civic engagement, fiscal transparency is one of the topics representatives from government, civil society, corporates, academia and media will discuss, which will likely include technology-mediated measures of enablement.

The OGP was announced in 2011, alongside the onset of the Arab Spring in late-2010. Three years hence, on the occasion of the Bali regional conference, we thought it might be useful to review the status of fiscal transparency indicators for four countries across two regions. Indonesia, Philippines (East Asia), Tunisia and Morocco (North Africa), being middle income countries with authoritarian pasts, are likely to offer fertile ground for fiscal transparency advances. Indonesia and Philippines are OGP founding members. The Philippines is a Lead Steward of Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency (GIFT). Tunisia and Morocco are in transition, following the Arab Spring. Tunisia is part of the 2014 OGP cohort, while Morocco is not a member.

A range of accessible global benchmarks and methods provide insights into regulatory frameworks and systems in our sample. Systems performance measures include IMF’s Fiscal Transparency Code (currently undergoing major revision), Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability framework (PEFA), the International Budget Partnership’s Open Budget Index (OBI), Financial Management Information System (FMIS) implementations, websites of Finance ministries and national open data sites. Regulatory/institutional status is captured by Freedom of Information (FOI) laws and OGP plans. Much of this information is nicely aggregated in a dataset developed by Dener and Min for an analytical study, ‘FMIS and Open Budget Data’, which builds an unprecedented dataset of key indicators that measure the current status of a country’s web platforms for publishing open budget data from FMIS, after reviewing Public Finance (PF) websites of 198 countries and use of 176 FMIS solutions.

We review data for these countries along three lines of enquiry: (i) starting point of fiscal transparency, (ii) regulatory/institutional status, (iii) channels of fiscal information access, salient interests. As we look beyond Bali to the global OGP meetings in New York in September, we reflect on lessons, at the intersection of politics, technology, fiscal transparency and openness reforms, from these countries.

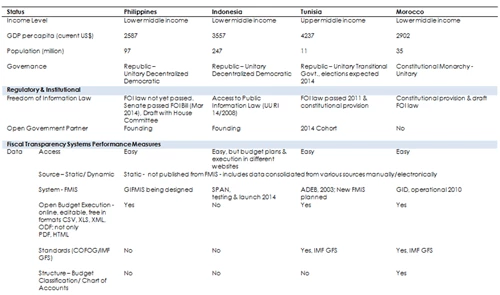

Table 1 summarizes key highlights and benchmarking indicators of regulatory and fiscal transparency performance for our sample.

Click HERE or on the image itself to enlarge the table.

Philippines released a national open budget data portal in Jan 2014 under the sponsorship of the Office of the President, but an FOI law remains in draft. While Philippines has made great strides, making budget transparency mandatory under the Transparency Seal according to the Philippines OGP progress report, there remain significant challenges at the national and sub-national level in tracking budget execution. This has been vividly illustrated in the case of reconstruction spending after Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda. A national FMIS is not yet in place, but is likely to be rolled out in 2-3 years. A major challenge through the end of the reformist administration towards 2016 will be increasing budget credibility and associated fiscal transparency concerning actual spending.

Tunisia adopted a FOI law (May 2011) after the revolution, and recently celebrated the passage of its constitution nearly three years later. Tunisia is developing the region’s first open budget data portal, including interactive expenditure analysis tools such as Boost. However, it lags on fiscal transparency indicators and operation of a foundational FMIS to supply data. Tunisia has made steps towards citizen engagement by developing a citizen’s budget and civil society-led platforms such as Marsoum41, to support FOI requests, including via mobile.

Morocco swiftly passed a new constitution in 2011 following the Arab Spring, including right to information, petition, propose legislation and consultation to foster a more participatory democracy. Draft organic laws have been prepared following dialogue with civil society and an FOI law is in progress. An FMIS which became operational in 2010 provides a firm foundation to supply open budget data. However plans for publishing open budget data are lagging. Morocco publishes citizen budget data, but the engagement strategy and roadmap are not clear. A draft budget law introducing programmatic and performance informed budgeting are being debated by parliament, to enhance transparency and accountability in public resources. Although Morocco has not formally applied to OGP, it has expressed interest and is working on eligibility criteria.

Fiscal Transparency & Openness: Politics, Technology and Domestic Demand

Undoubtedly, the digital era has boosted the global dialogue on transparency as a means to catalyzing government accountability for improving services to citizens. However, it also throws up some puzzling questions: Can the confluence of domestic constituencies, global norms, peer groups and enabling technologies (FMIS and web-based) provide an impetus to fiscal transparency and openness reforms? What is the role of politics?

We know from recent studies that transparency initiatives are enabled or constrained by drivers such as level of democratization, degree of political will, broader political economy(Khagram et al, 2013; McGee and Gaventa, 2010); and on the demand-side by factors such as capabilities of civil society to access and use information, linkages to collective action and mobilization, and integration into the policy cycle (Kuriyan et al, 2011). In the Philippines, the openness agenda is driven by Department of Budget Management (DBM) and has the active executive support of the Office of the President. Drivers for reform in Indonesia spring from the President’s Delivery Unit, also the executing agency for OGP, with some support from National Statistics. In Tunisia, the political impetus followed the revolution and the transition government’s desire to break from past secrecy codes. These new transparency policies are now enshrined in the constitution. In Morocco, new governance principles and rights in the 2011 constitution directly respond to citizen’s demands for transparency and participation following the Arab Spring. Insights from the fiscal transparency and openness agenda in these countries suggest that an important step is to assess degree of political will and key drivers of such initiatives. Put simply, are there champions in government who can create a space for reform, to sustain the use of technologies and policies to implement fiscal transparency & openness?

Our quick assessment (Table 1) shows that these countries have different baseline levels of success in managing public finance data, systems, openness, citizen engagement and FOI. Technology can be an enabler of demonstrable progress through web-platforms (e.g., Tunisia and Philippines). A fundamental issue remains going beyond a veneer of openness (laws approved and web-platforms built) to matching supply and anticipated demand for budget prioritization and execution data. FMIS solutions can provide real-time, transactions-based execution data, which can be shared in innovative ways with citizens (e.g., Philippines People’s Budget). However, in the absence of timely budget execution tracking or detailed data by sector, region, or procurement weakens the prospects of translating ‘open data’ into insights for citizens and, limits opportunities for detailed evidence-based analysis. Furthermore, in some countries, Subnational expenditures and State-owned Enterprises represent a major share of the public resource allocation pie considering essential public services provided. Following the money there remains more fragmented than at the national level and is vital. These concerns suggest the need for a comprehensive and holistic approach towards fiscal transparency and openness, which not only requires a unified legal framework, but also more integrated/interoperable systems, and mutually reinforcing levers such as reforms of budget, technology (FMIS and analytics) and corporate governance.

The OGP is grounded on a broad notion that global norms, peer groups and international collaboration can advance transparency and accountability. A deeper challenge remains in ensuring traction is gained from domestic demand for access to information, notably on how public resources are spent, and willingness and ability (e.g., through functional FMIS and consolidated accounts) of bureaucracies at national and subnational levels to proactively share PF data with citizens. The middle-class and digitally savvy constituencies are likely to be allies in this endeavor, beyond executive champions. Both the credibility of national budgets and the OGP will depend on making meaningful budget execution data available to citizens for openly tracking how public resources are allocated and actually spent.

Special thanks for feedback and guidance to Cem Dener, Sr. Public Sector Specialist, Nicola Smithers, Lead Public Sector Specialist and Saw Young Min, Jr. Professional Officer.

Image source: A Warli Tribal Painting by Jivya Soma Mashe, India via Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons 2.0 Generic license

Table source: 2012 http://data.worldbank.org; 2013 FMIS and OBD Dataset

NOTES:

[4/30/14 | 12:45pm] This post has been edited since its first appearance at 8:30am. The first paragraph has been added to point out that this posting is part of the monthly series on digital governance.

Join the Conversation