- a disciplined and centralised management of economic ‘rents’, which is usually associated with a strong, visionary leader or leadership;

- one single or dominant party;

- a competent, confident economic technocracy;

- a strategy to include, at least partially, the most important political groups in the country; and

- a sound basic development policy framework.

By contrast, four factors were found to be massive inhibitors of development:

- significant ethno-linguistic diversity;

- little or no central disciplining / constraining authority;

- a ‘winner takes all’ constitution; and

- the absence of a visionary and developmental leadership.

I found the argument and the evidence compelling. In my (new) job here in AusAID I reflected on the implications of these findings for our program in Papua New Guinea, a major strategic partner for Australia. It is hard not to conclude that PNG could be the model for the ‘where development is difficult’ category. It is characterised by extreme historical, geographic and cultural diversity. Governance is characterised by the absence of any strong sense of national identity and extremely weak political and social cohesion. Many citizens have little engagement with the state, imposing few demands for improved services, and receive few benefits from the State. Informal institutions prevail over formal institutions. PNG politics is strongly patrimonial: it is shaped by the ‘big man’ culture of personalised politics where elites and politicians provide benefits to clients and supporters. MP’s spend big to win office and there is an expectation that the MP will reward family and supporters appropriately. There is no constraining authority at the political centre to discipline this system of rent management.

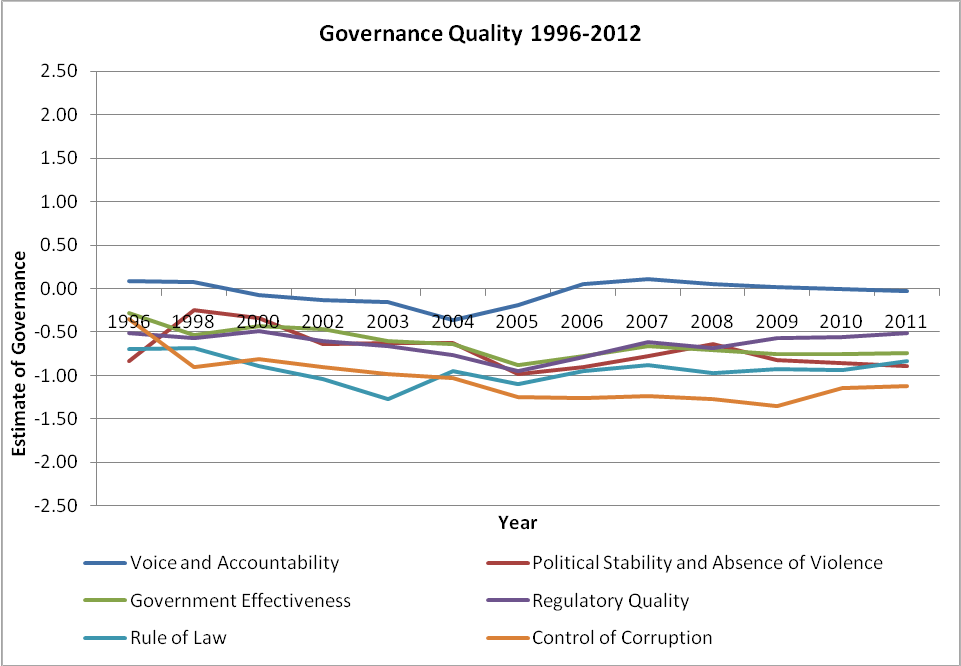

The data suggest that there has been little if any improvement in PNG governance over the last 15 years. The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators show all six categories of governance are worse today than they were in 1996:

These figures may grim reading for AusAID. Since 1975 total Australian ODA to PNG has totalled almost $25 billion, of which over $14.5 billion can be considered as spending on ‘governance’ in one form or another. So the question is, with what we know now what do we do differently? The overarching conclusion of this excellent ODI research is that we must ditch Principal-Agent assumptions underpinning much development work in such regimes. Put this together with the other things we know (function not form, build on what’s there, context is all, institutions grow endogenously etc – readers will know the song sheet…..), what do they all mean for any approach to strengthening governance in PNG?

While I doubt there are any quick and easy solutions, there may be some things we can do differently on Monday morning. First, we have to recognise that we may have to make a choice between supporting the machinery of government – the Executive – and actually ensuring services are delivered to those that need them. The Executive often is not very interested in execution. We may need to accept that supporting the structures of the state may not contribute effectively to poverty reduction. This means we have to find other, non-state modalities for delivering ‘development’. Second, we may need to accept that the issue in PNG is not about the volume of aid; it is about how to change institutions and the incentives of politicians. More aid may make the problem worse, by weakening the incentives to raise revenue domestically, thereby undermining domestic accountability. Third, we should (finally) give up the assumption that ‘building the capacity’ of individuals and organisations in the government will make much of a difference to service delivery at the front line. The best we can hope for is a difference in some places at the margins.

We need to recognise that in these circumstances the political elite, the leadership, has few incentives to use the bureaucracy as a developmental instrument, in the same way that say Korea did in the 1960s and 1970s, and that Rwanda and Ethiopia are doing today. Maybe the best we can do is to ensure the survival of the ‘shell’ of the state in order that the macro-economy is reasonably well managed and that there is a sufficiency of security to prevent the downward spiral to conflict. Our objective here could be stability at minimum cost.

Fourth, we need to think more creatively about how to build on local structures at local level: structures that are visible, legitimate and have the capacity to bear a greater load. Never mind that these structures don’t look like ones we know and love: we need to experiment and be willing to take risks. Fifth, we may need to be willing to put a greater share of our funding outside the government system and increasingly rely on what is now called Community Driven Development. If the state has failed let us acknowledge this and work with non-state providers. Finally, we know that MPs and citizens like direct funds – funds that MPs can do with as they like. Why not give them an extra $1m each to spend, but with strict conditions and accountabilities? This would seem like a win-win: MPs get extra cash and the credit for delivering the cargo, while learning at the same time the nature and workings of accountability. Citizens get to benefit from services provided by their MPs and thus begin to develop developmental expectations from them. This is the beginning of state-society relations: when wantoks begin to morph into citizens, and PNG may begin its journey to real, as against imagined, statehood.

These issues are being considered. The alternative is to continue what we have being doing for the last twenty years. It is clear however that one more push doing this, but trying a little harder this time, won’t work; history and the research from ODI tells us this. But designing a program knowing this remains tough. We know enough to know what should guide us on Monday morning, but we often end up having to triangulate among evidence, the desire to spend, and the legitimate priorities of our partner governments. But hey, whoever said development, let alone this governance business, was easy?

-----

Graham Teskey is a Principal Sector Specialist at AusAID. This post represents Graham Teskey's views and not necessarily those of AusAID.

Development as a collective action problem. ODI, 2012

Join the Conversation