I consider myself a pretty lucky person. I often work across the beautiful islands of the Caribbean, with their glistening turquoise seas, the lush greenery, fresh tropical fruit… I could go on, but I think you get the idea. Paradise is not always perfect, however: Beneath the postcard views is an often not-so-perfect public health system.

A recent “close encounter” in the Caribbean served as a stark reminder of this truth. Different from the movie “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”, it didn’t involve little green men nor giant floating spaceships, but something just as unknown, at least to me: chikungunya, a viral disease transmitted by the bite of infected mosquitoes.

Unfortunately, I was infected with chikungunya a little over a year ago during a work trip to the Eastern Caribbean in support a results-based financing project for the health sector. Our team was de-briefing near the ocean when it happened: I felt a quick sting from a mosquito bite, but didn’t think much of it. I felt unusually tired that evening, and by the next morning a number of other symptoms appeared – it was indeed chikungunya.

I can tell you that everything you may have heard about the disease is true – it can bring severe joint pain, weakness, and fatigue.

In the last 18 months, chikungunya has hit the Caribbean hard. According to recent data from the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA), the first cases in the current outbreak appeared on the island of St. Martin in December 2013. As of today, chikungunya cases have been confirmed in 23 of the 24 CARPHA member states [1].

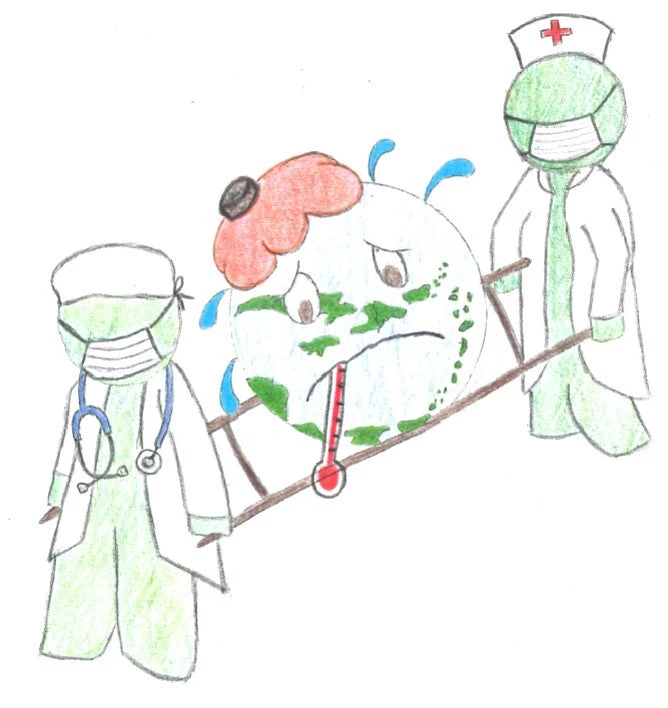

As the Caribbean was dealing with chikungunya, another public health threat – Ebola – emerged across the Atlantic, bringing devastation to West Africa. With chikungunya on its shores and an Ebola outbreak that looked to be spreading globally, Caribbean governments faced a potential public health emergency.

Was the region prepared to respond to such an emergency? The answer is a bit of “yes”, but mostly “no.”

On the “yes” side, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) has implemented the Advanced Passenger Information System (APIS) managed by the Implementation Agency for Crime and Security (IMPACS). This system requires that all private and commercial flights to or from CARICOM member states submit advance passenger information—including on any potential infectious disease—prior to arrival or departure. APIS came into effect in 2007 in the 10 CARICOM member states.

On the “no” side, results from an Ebola survey conducted by CARPHA, in partnership with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), revealed gaps across the board among all CARPHA member states, namely in the areas of Ebola preparedness, points of entry, transportation readiness, general infection prevention and control, and Ebola-specific infection prevention and control.

Country preparedness surveys, also conducted by CARPHA and PAHO, also found that no CARPHA member state had reached full compliance with the International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005. The purpose of the IHR is to help countries prevent and respond to acute public health risks, which have the potential to cross borders and threaten people worldwide, by minimizing impact on travel and trade.

The lack of IHR compliance among Caribbean countries, and the increasing levels of travel within the region and globally, are key factors contributing to regional health security gaps.

Chikungunya has already hit the Caribbean. Regarding Ebola, while the likelihood of a case in the Caribbean is low, the consequence of one imported case could devastate both the population’s health, as well the tourism industry, the economy, security and public safety across the region.

To strengthen the Caribbean’s capacity to respond to public health emergencies, the CARICOM Heads of Government met in Trinidad and Tobago last November to endorse regional efforts to address chikungunya, in the form of four priority actions. On Ebola, the group adopted a 10-Point Plan of Action to Stop Ebola There and Here. In addition, CARPHA was mandated to coordinate the region’s efforts on these fronts.

The World Bank has engaged with CARPHA and supported actions under these regional efforts, which include multi-sectoral work, strengthened coordination at ports of entry, proper training and equipping of staff and laboratories, engaging airlines for specimen transport, and creation of rapid response teams, public health campaigns, simulation exercises, and harmonized regional response policies, among others.

Fortunately, today, I am chikungunya-free. Although it was a long and painful process, I recovered from my close encounter with a viral disease. The Caribbean public health system has also embarked on its road to recovery -- towards a strengthened public health system prepared to respond to chikungunya, a potential Ebola threat, or any other health emergency.

Thanks to coordination efforts across CARICOM countries and a high-level commitment from CARICOM Heads of State, I’m certain the Caribbean region’s road to recovery will be less painful than mine!

Follow Carmen Carpio on Twitter: @CC_CarmenCarpio

Follow the World Bank health team on Twitter: @WBG_Health

Related

St. Martin News Network: Ministry of Public Health prepared for regional Ebola disease simulation exercise

Radio Cayman: Cayman Islands joins in regional Ebola simulation exercise

Caricom Today: Caribbean successfully conducts Ebola simulation exercise

World Bank Ebola Response Fact Sheet

[1] Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, BES Islands (Bonaire, St. Eustatius, Saba), British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Curacao, Dominica, Grenada, Haiti, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, St. Maarten, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and Turks and Caicos Islands

Join the Conversation