In my post last week, I described a counseling intervention that aims to increase the uptake of modern contraceptive methods, without (a) increasing (perhaps even decreasing) switching and discontinuation of methods shortly after adoption, and (b) reducing client welfare and satisfaction. This week, I quickly describe our cross-randomized intervention providing discounts for contraceptives and summarize our findings from the experiment.

Before our study began, the prices for the four main modern methods available for adoption at HGOPY – copper IUD, implant, injectable, and the pill – were as follows, respectively: CFA 5,000, 5,250, 1,250, and 1,500, respectively (1 USD ≈ 550-600 CFA Francs). There was also a small fee for clients who wanted to purchase condoms. In addition, removals of the two long-acting methods (the IUD and the implant) were as costly as the adoption. Under our study, we made removals of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) free and made it universal to provide a free packet of 20 condoms for each client counseled. In addition, each study participant received the following cross-randomized prices:

Specifically, the prices were revealed – all at once for the whole vector of available methods – after the client had chosen a method under one of the counseling regimes, as described in detail in last week’s post. The clients were told that these prices are valid for one year from the date of the counseling session, meaning that not only could they come back and adopt any method under those prices, but they could also adopt something now and then come back and switch to another method by paying the randomly assigned prices at the outset for each adopted method. The prices were revealed after the client made a choice to ensure that the client chose the method most suitable for her needs unconditional on the price: of course, the final adoption decision, distinct from the choice of the client, did depend on the price as well. If the client asked the nurse counselor what the price was and insisted that she needed to know the price before deciding, the counselors knew how to navigate to the ‘price button’ to reveal the vector of prices and then returning to where they were in the counseling flow.

Some people reading our paper have been worried about clients individually randomized into higher prices going elsewhere to adopt the same methods cheaper. After surveying the clinics, large and small, in the area surrounding HGOPY, we are convinced that the prices are not cheaper elsewhere: not only the upfront costs of adopting each method are similar elsewhere, but also services that are free at HGOPY, such as counseling, removals of LARCs, and condoms are costly elsewhere. Hence, we are not worried about the control group (receiving high prices) adopting methods elsewhere. Furthermore, if this were to happen, we’d also be able to assess this through follow-up phone surveys – conducted at two-, 16-, and 52-weeks after the initial counseling session.

So, we have a two-arm randomized counseling intervention, crossed with random discounts for contraceptive methods: what do we find?

We examine whether the client left the hospital with (a) a LARC (implant or IUD), (b) a SARC (injectable or the pill), or (c) another method (condoms, lactational amenorrhea method or LAM for those eligible, a traditional method, or no method), which is denoted as “adopted nothing” in the table below. The typical-use failure rates, i.e., 12-month pregnancy rates for people using these methods, for these categories range from less than 1 % for LARCs, 6-9% for SARCs, and above 15% for condoms and other methods (LAM is at least as effective as SARCs when used correctly but can only be used for a limited amount of time).

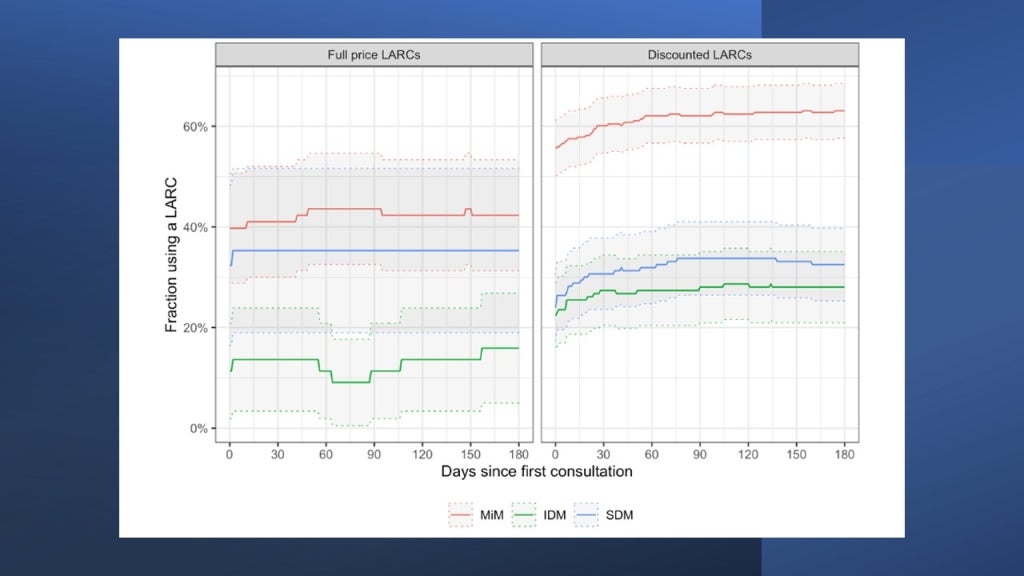

The figure below shows the share of those who adopted a LARC (y-axis) by counseling regime and discount status (x-axis). To make the presentation simpler we lumped all discounts together and contrast them with the highest prices in the study: the average discount is about an 80% reduction from the highest price of CFA 4,000 and ranges from 50-100% for each client.

42% of the clients who have a method-in-mind (denoted by MiM) adopt a LARC before leaving the hospital, while this share increases to 62% among those receiving a discount. If a client did not have a method in mind and was randomized into the status quo counseling regime (IDM), LARC uptake drops to barely above 10% under full price but jumps to just under 30% under a discount – an almost tripling of LARC take-up. So, both these groups are price sensitive and the increases in take-up are quite large: as expected, people with a method in mind have higher rates of take-up but they are also still price sensitive.

What’s really interesting is the group – also with no method in mind but is randomly assigned to the alternative counseling regime (SDM). Comparing SDM to IDM under the full price (the red bars), we see that take-up of LARCs more than triples under the alternative counseling regime compared with the status quo. Furthermore, this approach, where the client is told that the ranking of methods in their order of suitability for her elicited preferences, renders the clients price-insensitive: offering discounts has no discernible effect on take-up under this regime. In the appendix section of the working paper, we present a model of individual utility maximization, where the clients care about the price of LARCs and the perceived returns to adopting them. As the top ranking is a LARC for most of the clients, SDM causes a substantial shift in the distribution of perceived returns to adopting a LARC and, hence, increases willingness-to-pay (WTP) – above the full price in our study for many. Therefore, offering discounts to them has no further effect on take-up.

These are large effects, with the effect of alternative counseling particularly promising as the fixed cost of training providers is more cost-effective than providing discounts – even though the discounts are also cost-effective by most standards, if the increased LARC uptake translates into the expected reductions in unintended pregnancies. Now a few caveats for the readers to consider:

· The gains in LARC uptake are achieved primarily by people who would have left HGOPY having adopted no method or one with substantially lower typical use effectiveness. In other words, the discounts have no effect on SARC take-up: if our interventions were mainly switching people from the pill and the injectable (with typical use failure rates around 6-9% for 12-month pregnancy rates) to the implant and the IUD (same rates less than 1%), these impacts would be expected to translate to a much lower number of unintended pregnancies averted. In our study population, interest in SARCs is low and there are no direct or cross-price effects from the discounts on their uptake: nor is there any effect of counseling.

· One of the worries about the alternative counseling approach is that it might lead to reductions in client welfare and satisfaction, resulting in a lower probability to return to that facility for health services, lower trust in the system, etc. – IF, that is, the client finds the SDM approach disrespectful. Follow-up surveys immediately after the counseling session finds that (a) the quality of the FP counseling services provided is very high (per a checklist of quality-of-service delivery developed by researchers from the Population Council); (b) client satisfaction is very high and 90-95% of clients say they would return to the clinic for FP or other services; and (c) none of these high marks are differential between counseling interventions. Therefore, we conclude that SDM increased take-up of modern contraceptives over IDM without causing worrisome tradeoffs in client autonomy, satisfaction, or welfare.

· A similar worry involves a large share of clients switching methods and, worse, discontinuing their methods soon after adoption. This could happen differentially between counseling interventions if, say, SDM systematically got rankings wrong and many clients experienced side effects that they did not expect or were not willing to tolerate. In that specific scenario, the outcomes measured at the end of the counseling session would be a poor proxy for the final outcomes, overstating the effects of SDM. However, both administrative data from the tablets on return clients and data from 16-week follow-up surveys that specifically focus on switching and discontinuation of methods indicate that this is not the case: if anything, the effects of the interventions increase slightly over time. This is because while switching and discontinuations are very low in our study population within 4-6 months after the initial counseling session, some clients who initially did not adopt a LARC or SARC come back to adopt one later (perhaps they needed to think about it or talk to someone; maybe they needed to gather money needed to pay the random price they received; or maybe they initially chose LAM and came back to adopt their chosen method when they stopped exclusively breastfeeding). The clients who return to adopt offset those who switch or discontinue. Hence, the large impacts on LARC uptake are likely to translate to reductions in 12-month pregnancy rates. [Please note that the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study, but not for receiving all the improved and discounted or free FP services, is that the client wants to wait at least 12 months before becoming pregnant, implying that we will interpret all pregnancies happening within a 12-month period as unintended.]

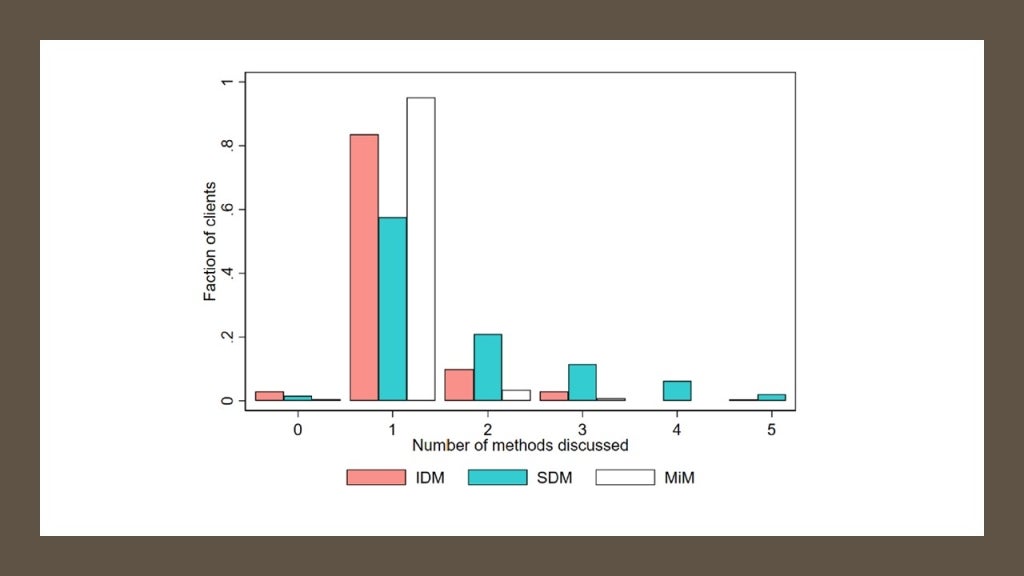

· A skeptical reader, who has spent many years in the FP field, might object that the clients are not getting “full choice” under SDM. That is a good point for debate, just as whether “full choice” defined as such is the ultimate goal to the exclusion of most other considerations (such as time constraints, choice overload, typical use effectiveness of the method, and so on). But, interestingly, SDM causes more clients to discuss more method in detail. Under IDM, the clients get the “90-second cliff notes” version of each method before they decide what method to discuss in detail. This approach produces the outcome that more than 80% of IDM clients discuss only one method in detail before choosing a method. Under SDM, there is no cliff notes version of all methods, but under 60% of clients discuss only one method in detail: more than 40% discuss at least two methods and more than 20% discuss at least three methods in great detail before making a decision. So, even from the perspective of delivering information on a “range of methods” to the client through counseling, it is not clear that IDM does better than SDM.

· Finally, we estimate the heterogeneity of impacts of providing discounts by non-parametrically estimating conditional average treatment effects (CATE) by fitting causal forests under each of the three counseling regimes. We find that the group that is relatively strongly affected by price discounts is comprised of younger women, who are more likely to be students, want to wait longer before becoming pregnant: in other words, these are women motivated to delay pregnancies but with credit constraints. These findings indicate that price discrimination using easily observable (and hard to manipulate) characteristics, such as age, might be effective.

That’s the summary of the findings from this experiment. The adaptive experimentation is currently ongoing, along with follow-up surveys that assess quality of service and satisfaction; switching and discontinuations; and 12-month pregnancies. I will write about that phase separately in the near future.

Join the Conversation