Tackling global warming

Global warming is bad and humans are to blame for it. Preventing dangerous climate change by mitigating greenhouse gas emissions is essential for the sustainability of our planet. Efforts to conserve and restore degraded tropical forests landscapes are considered cost-effective ways to achieve climate mitigation—they could contribute to as much as a 24-30 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions! But how do we get there?

PES is one promising approach

One promising approach to efficiently induce forest conservation, while primarily benefiting poorer households, is Payments for Environmental Services (PES). PES programs pay individuals or communities to provide environmental goods and services, such as planting trees or preserving landscapes. By compensating individuals for these actions, PES aligns individuals’ private incentives with the public environmental benefits. Moreover, PES can play a role in eliminating rural poverty — just like popular social protection programs, PES may be structured to target poor households and offer supplementary employment.

There is robust evidence, with examples from Uganda, Mexico, and Ghana (discussed on this DI blog), that PES are effective at delivering on their primary goal: conservation outcomes. But the evidence on whether PES programs benefit poor households is more limited. A recent systematic review reports mixed effects and points to a lack of well-identified studies on this question. Additionally, there are reasons to think PES may not benefit poor households as one would hope: PES employment may displace on-farm labor, and local benefits from environmental goods (such as planted trees, or erosion control) may be captured by wealthier land owners.

A PES program designed for the rural poor

A recent paper by Adjognon, van Soest, and Guthoff tests exactly this. Their study is set in Burkina Faso, where remote sensing of tree cover in key degraded forests revealed as low as 40% tree cover. In response, the government is implementing afforestation campaigns as part of their Forest Investment Plan (FIP).

After an initial planting of trees, groups of randomly selected individuals were enrolled in PES contracts, whereby they receive additional payments based on verified tree survival rates. Growing conditions in Burkina Faso are harsh, and survival rates can be improved by watering plants, putting up fire breaks, maintaining the holes in which saplings are planted, and by removing dead organic material in the plant's vicinity. Although these activities required time and effort throughout the year, the timing of the payments coincided with the lean season, when farmers were most at risk of food insecurity. As regular readers of the blog may expect, the impacts of PES on food security were then estimated by comparing randomly enrolled individuals to the randomly not enrolled.

Drum roll…

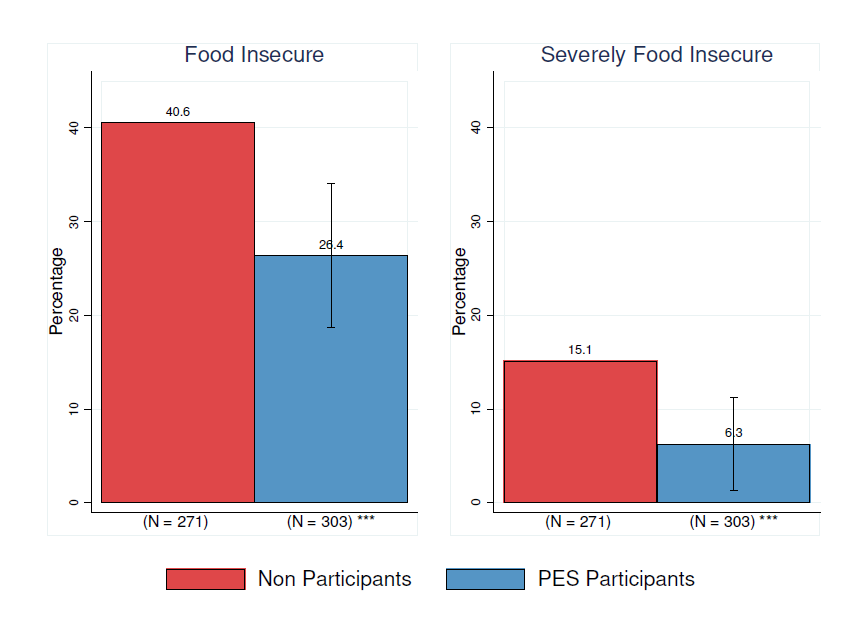

The news is good. In Burkina Faso, food (security) did grow on trees! — the study finds food insecurity fell by 35%, and severe food insecurity fell by 60%. Now, everyone has their own favorite measure of food security—the study finds this result holds across a broad range of measures of food security and hunger. One likely reason the program was so effective was the timing of the payments, during the lean season, when most farmers had exhausted their stock from the previous harvest.

In line with a large body of work on cash transfers and cash-for-work programs, this study found no evidence of increased consumption on temptation goods; instead, transfers were spent mostly on cereals, meat, and pulses.

Lastly, agricultural productivity was unaffected. This suggests on farm labor was not displaced by PES work — although tree maintenance activities occur throughout the year, including during agricultural seasons, productive land is scarce in targeted regions. This generates surplus labor that could be employed by PES programs.

Takeaways

In the drylands of the Sahel region, an ostensibly clear tradeoff is whether to invest in forest conservation programs to honor commitments to the Paris Climate Agreement, or instead in programs that support pressing food security issues for the millions of vulnerable constituents. This study demonstrates that synergies are possible—there are opportunities for governments to leverage international climate finance to reduce the costs of addressing food security challenges locally. On fixed budgets, this enables governments to reach more households with social protection programs while contributing to global emission reduction goals.

Join the Conversation