Teachers are important. And many teachers in low- and middle-income countries would benefit from support to improve their pedagogical skills. But how to do it? Again and again, evidence suggests that short teacher trainings – usually held in a central location – don’t do much of anything to improve teacher practice. Likewise, much teacher training is overly theoretical and doesn’t translate into practical pedagogical improvements.

Providing teachers with one-on-one coaching is a popular alternative. A coach comes to the classroom, observes the teacher, and provides practical feedback. It makes sense. As Kotze and others put it (in turn paraphrasing earlier authors), “Teachers only learn to do the work by doing the work, and not by being told to do the work, or being told how to do the work, or being told that they will be rewarded or punished for outcomes associated with the work.” A recent review of U.S. evidence shows big impacts of coaching on both teacher practices and on student learning. But those big effects are concentrated in small-scale programs: Effects tend to be much smaller when implemented at scale. Outside a high-income environment, a teacher coaching pilot in South Africa compared coaching to a more traditional training at a central location. Students whose teachers received coaching learned twice as much as students who teachers received training.

But implementing coaching at scale presents a number of challenges. First, it’s costly. Second, where do you find the coaches? Technology has the potential to help. In a follow-up experiment, researchers in South Africa compared on-site coaching to “virtual coaching” to compare effectiveness. Initial results have just come out in Kotze, Fleish, and Taylor’s “Alternative forms of early grade instructional coaching: Emerging evidence from field experiments in South Africa.”

The experiment: 180 schools in relatively low-income areas were randomly assigned, 50 to on-site coaching, 50 to virtual coaching, and 80 to a comparison group. Teachers from all 100 treatment schools received detailed daily lesson plans, materials relevant to those lesson plans, and a couple of days of centralized training at the beginning of the school year. The content focus was English as a second language for children in the first three grades of primary school.

Teachers assigned to on-site coaching received at least 3 visits per term from a coach. A given coach would cover 32 teachers.

Teachers assigned to virtual coaching had just one coach. That person provided coaching...

Teachers in the virtual coaching group also received their lesson plans on a tablet, integrated with various audio and visual resources. At the beginning of the year, they received one additional day of in-person training to familiarize them with the tablet.

A key difference is that the on-site coach provides both encouragement and feedback, whereas the virtual coach provides mostly encouragement, as she cannot observe teachers in their classrooms and provide direct feedback. In addition, the virtual coach provides more frequent follow-up, albeit not in person.

The results: Students have better English listening comprehension in the two coaching interventions, with no clear difference between the two interventions.

Source: Kotze, Fleisch, and Taylor 2018

Students in the coaching groups also do better on English vocabulary.

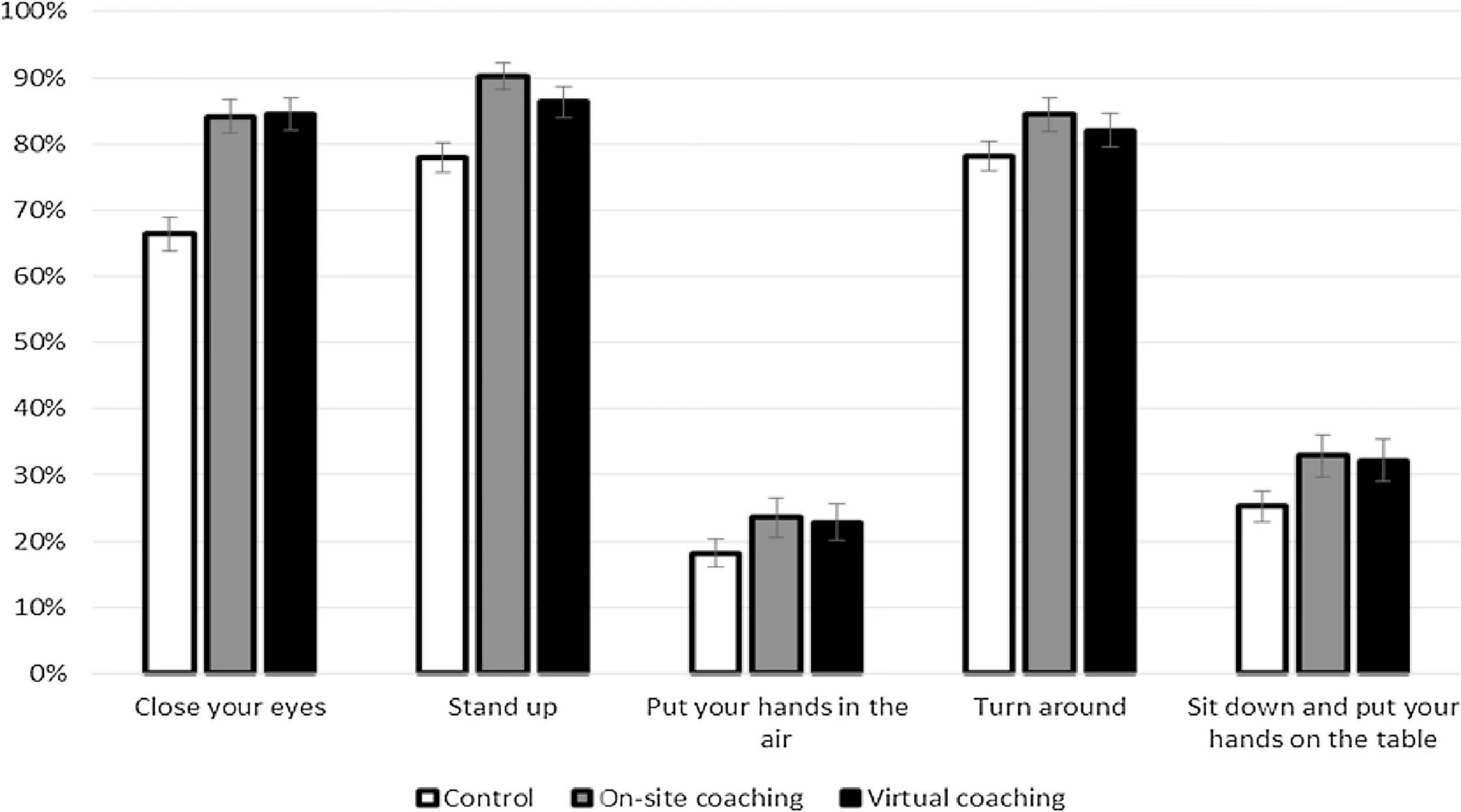

Classroom observations show that teachers in both coaching groups are more likely to keep on track with the structured lesson plans, and they are more likely to use English when they are teaching English. An interesting spillover is that teachers in both coaching groups are also more likely to meet with “head of department” in their school on a regular basis. The existence of a coach (whether near or far) may prompt in-school mentors – who themselves tend to have a full teaching load – to provide more regular follow-up.

What problems does virtual coaching solve, and what problems does it not solve? Virtual coaching allowed just one coach to do the same work that three coaches did in the on-site coaching intervention. So virtual coaching has real potential to solve the problem of finding lots of high-quality coaches in low-performing education systems. It doesn’t, however, solve the cost problem: the per-student annual cost of the two programs was within US$5 of each other. On the one hand, on-site coaching costs more salary because it uses more coaches, but on the other hand, the virtual coaching model required an additional day of on-site training for teachers, tablets, and cellular data.

Take aways: The technology message of the World Bank’s World Development Report 2018 is that technology works best when it complements rather than substitutes for teachers. Virtual coaching is an example of using technology to complement teachers.

Bonus reading

- My blog post summarizes the U.S. teacher coaching literature review.

- Aker and Ksoll evaluate an adult education program with remote monitoring – by phone – in Niger and find a sizeable gain in learning. I blogged about it.

- Bruns, Costa, and Cunha evaluate a virtual coaching program in Brazil, where expert coaching delivered to school-based pedagogical coordinators led to small, significant gains in student learning.

Join the Conversation