In 2003, the Argentine province of Salta launched a new tourism development policy with the explicit objective of boosting regional development. This included improving tourism and transport infrastructure, restoring historical and cultural heritage areas, tax credits for the construction and remodeling of hotels, and a major promotion campaign at the national and international levels. As I have

noted before, evaluating the impact of these large-scale projects can be very difficult. Yet this is the challenge a recent

IDB working paper undertakes. Is the result, like Salta’s tourism slogan,

tan linda que enamora (so pretty you will fall in love)?

Using synthetic controls to form a counterfactual

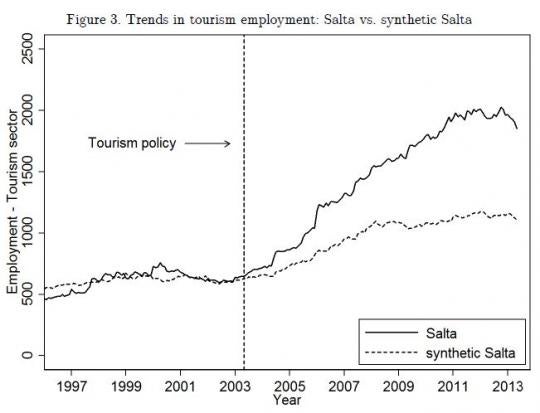

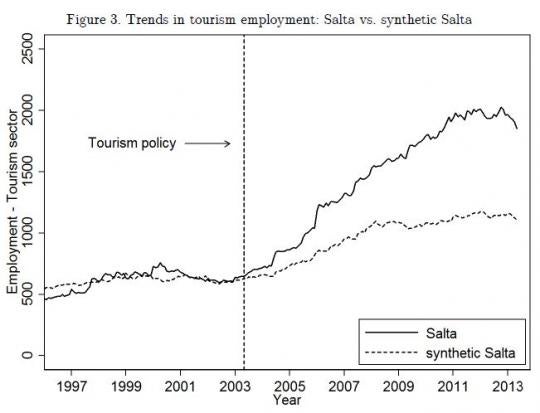

To tackle this tough evaluation question, the authors use the method of synthetic controls (explained in the previous blog post). They form “synthetic Salta” as a weighted average of other Argentina provinces. They can then compare tourism employment in Salta before and after the change to this counterfactual, as seen in this figure.

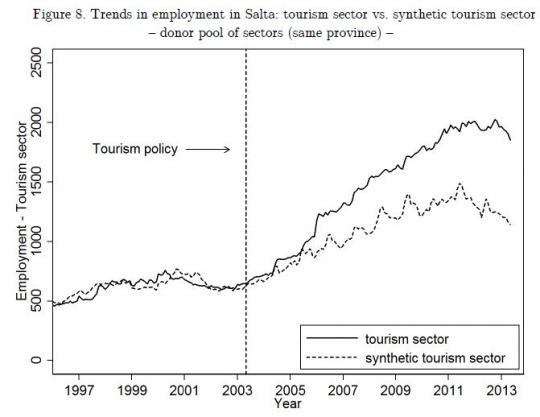

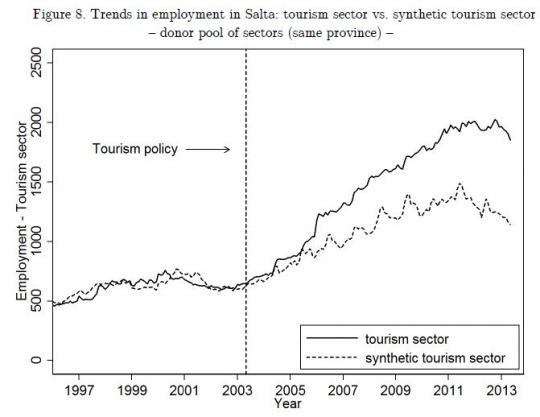

They also consider a second way of forming the counterfactual, by constructing the synthetic Salta tourism sector as a weighted average of other sectors in Salta, yielding this figure:

In both cases you see growth in tourism employment after the change – the authors estimate an impact of 10-11 percent higher employment per year as a result of the policy. As a further robustness check, they use additional sectors from other provinces, getting reasonably similar results.

The paper then does a very thorough job of detailing a large number of robustness tests, falsification tests, and placebo tests. For example, one thing that is typically done is to re-run the same analysis for every other sector or unit, and see whether the result you have is very different. Here’s an example:

You see that applying this method to the tourism sector yields a much larger gap in employment between the sector and synthetic sector than would occur if you applied the same method to any of the other 36 sectors in Salta during this time.

What might we be concerned about?

This paper does an excellent job of conducting lots of different checks, using lots of data before and after the reform, and because it uses regions within a country, rather than comparing across countries, holds relatively constant a lot of institutional and macro factors that worry me in applying this method across countries. Given how tough these types of policies are to evaluate, this strikes me as reasonably credible evidence.

My main concern though is basically a difference-in-differences type concern:

A final point to note in terms of applicability – this approach might work better in a relatively big country like Argentina with good data, compared to in small countries.

Using synthetic controls to form a counterfactual

To tackle this tough evaluation question, the authors use the method of synthetic controls (explained in the previous blog post). They form “synthetic Salta” as a weighted average of other Argentina provinces. They can then compare tourism employment in Salta before and after the change to this counterfactual, as seen in this figure.

They also consider a second way of forming the counterfactual, by constructing the synthetic Salta tourism sector as a weighted average of other sectors in Salta, yielding this figure:

In both cases you see growth in tourism employment after the change – the authors estimate an impact of 10-11 percent higher employment per year as a result of the policy. As a further robustness check, they use additional sectors from other provinces, getting reasonably similar results.

The paper then does a very thorough job of detailing a large number of robustness tests, falsification tests, and placebo tests. For example, one thing that is typically done is to re-run the same analysis for every other sector or unit, and see whether the result you have is very different. Here’s an example:

You see that applying this method to the tourism sector yields a much larger gap in employment between the sector and synthetic sector than would occur if you applied the same method to any of the other 36 sectors in Salta during this time.

What might we be concerned about?

This paper does an excellent job of conducting lots of different checks, using lots of data before and after the reform, and because it uses regions within a country, rather than comparing across countries, holds relatively constant a lot of institutional and macro factors that worry me in applying this method across countries. Given how tough these types of policies are to evaluate, this strikes me as reasonably credible evidence.

My main concern though is basically a difference-in-differences type concern:

- I worry that comparing to tourism in other Argentine provinces is biased because the policy diverts tourists from those provinces to Salta. This means that synthetic Salta has lower employment that Salta would have had without this policy (because the other regions suffer), so the effect is overstated. Of course for international tourists the spillovers could have instead been positive (come to Salta, and then also visit Jujuy) – in which case the bias would be understated.

- I worry also about spillovers within Salta – if the tourism industry is booming, this could draw away workers from other sectors, making them no longer such a good counterfactual.

A final point to note in terms of applicability – this approach might work better in a relatively big country like Argentina with good data, compared to in small countries.

Join the Conversation