Richer countries have more research published about them on average, which means that African countries tend to have fewer studies about them. But South Africa far outstrips the rest of the continent. In the sample of Das et al. (1985-2005, so a bit dated now), 46 percent of all publications from Sub-Saharan Africa were from South Africa, as you can see below. So I was thrilled to be in South Africa last week and see a vibrant research community doing research on the economics of education in South Africa, at the

Quantitative Applications in Education conference at the University of Stellenbosch’s

Research on Socio-Economic Policy group. Below is a rundown of just some of the interesting findings; follow the links for the full presentations.

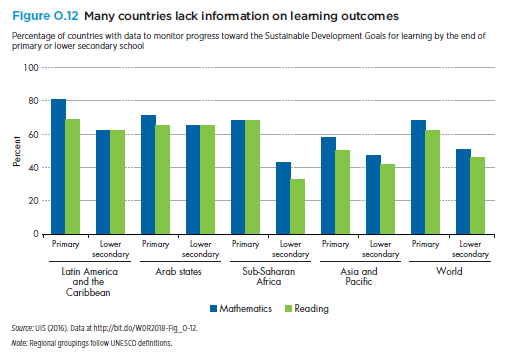

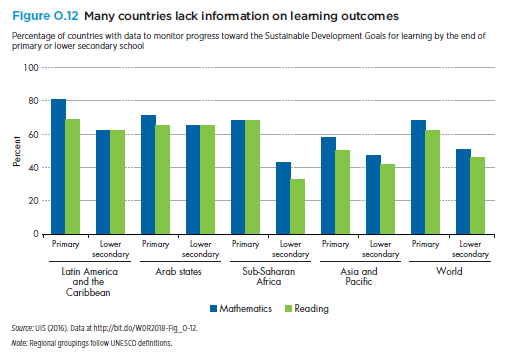

South Africa clearly has a rich, ongoing research program regarding education. Part of the reason that’s possible is that South Africa collects data on learning at multiple stages throughout the schooling process and makes it public. The World Development Report 2018 demonstrates that many countries don’t do this, as the figure below shows. Of course, “weighing a pig doesn’t make it fatter”: Measurement by itself doesn’t solve problems. But measurement can be a first step in identifying general and specific challenges and can be one ingredient in galvanizing public support for reform.

Source: World Development Report 2018

Publications on country by GDP Source: Das et al. 2013 |

Publications on different African nations Source: My construction, with data from Das et al. 2013 |

|

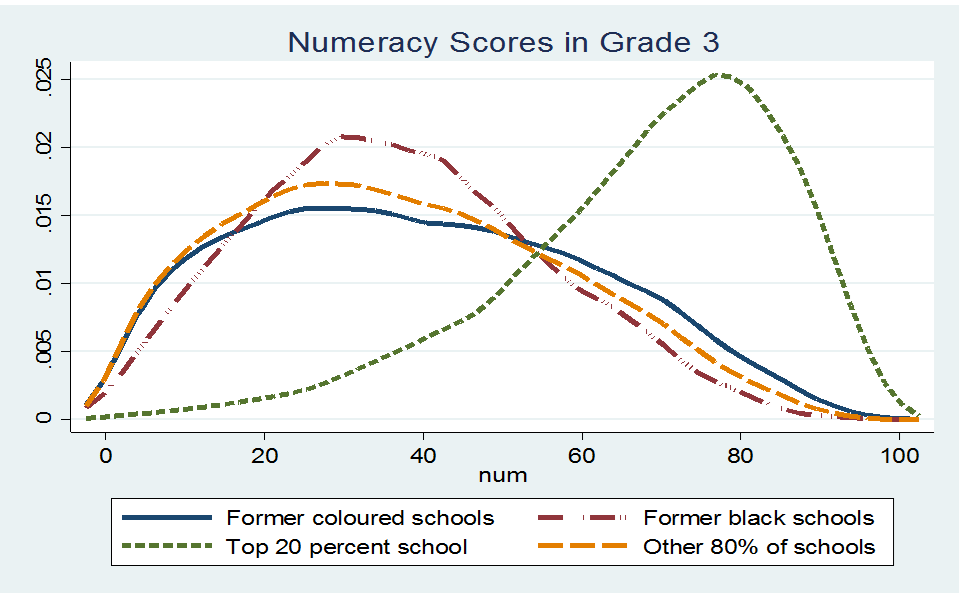

South Africa has made enormous progress in education, but don’t be complacent! Van der Berg gave a comprehensive presentation of statistics on progress and current performance across South Africa’s education system. |

|

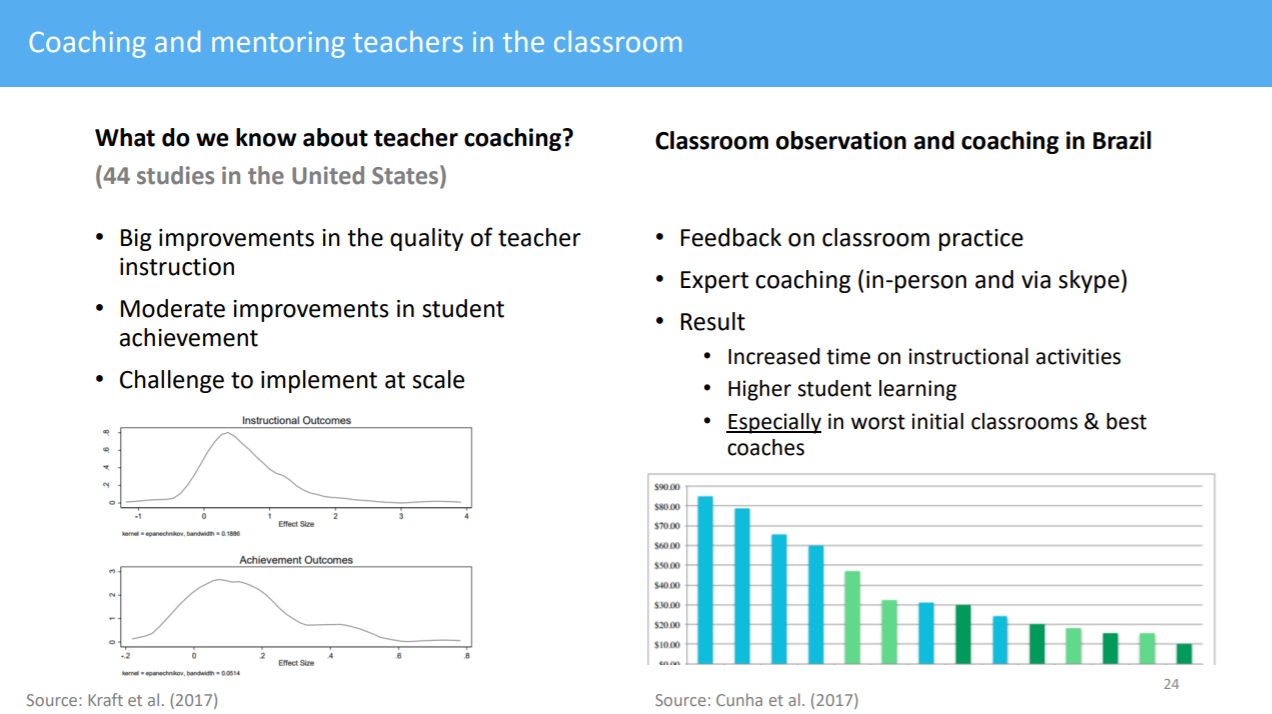

How do you improve early grade reading? Taylor presented the results of an RCT that compared teacher training to teacher coaching to parent training. Teacher coaching takes the prize! You can read a full report on this evaluation or a simple infographic. |

|

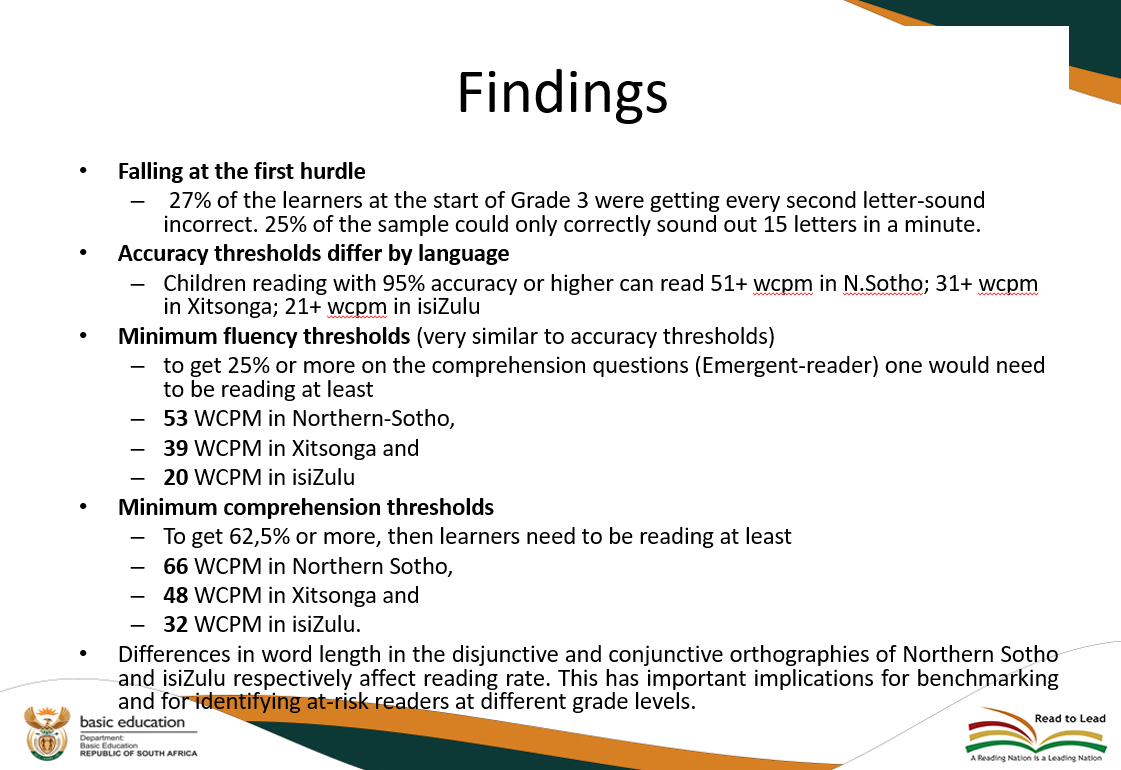

How quickly does a child need to read to be able to understand? At what age should they be able to do that? Those benchmarks are well established (or at least well researched) for English, but with the policy shift toward mother-tongue instruction, educators in Africa are often without guidance. Mohohlwane presented exciting work on the challenges of translating benchmarks and new efforts to create benchmarks in three languages (isiZulu, Northern Sotho, and Xitsonga). |

|

I gave an overview talk – based on background work for the new World Development Report – on what we know about getting the most out of teachers: effective professional development, motivation and incentives, and teaching to the level of the students. |

|

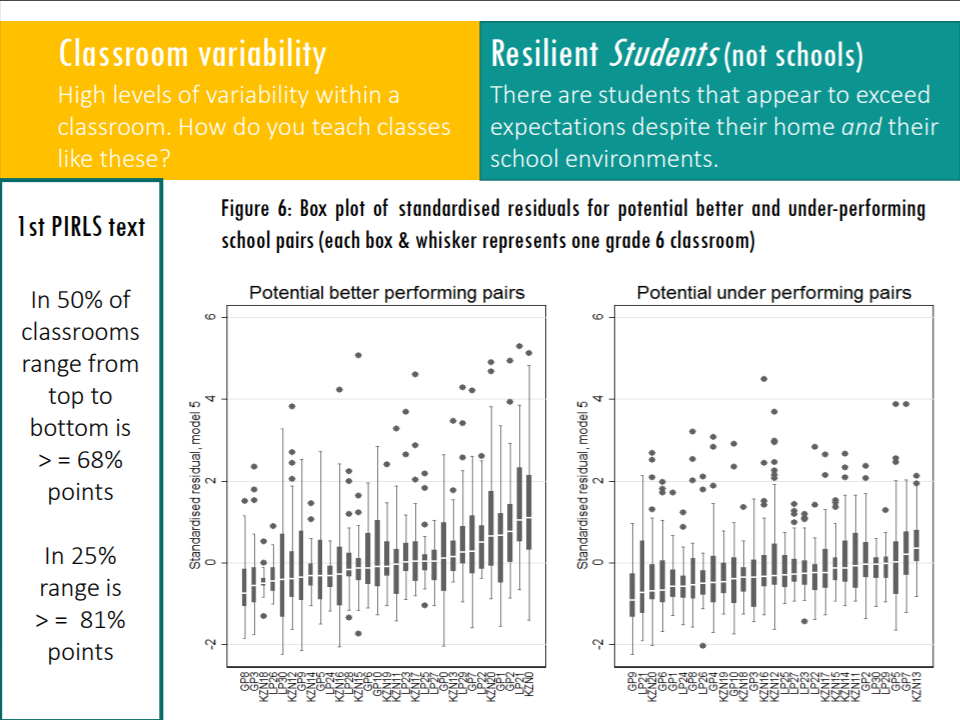

Wills highlighted the limits of school choice when key requirements aren’t fulfilled and demonstrated the deep challenge of identifying high-performing schools, as opposed to high-performing students. You can read the paper here. |

|

What difference does a good school make? Von Fintel and van der Berg used students who switch schools to identify school effects. The result? About 0.28 standard deviations in math and 0.06 in language (albeit the language score is double for black students). You can read the paper here. |

|

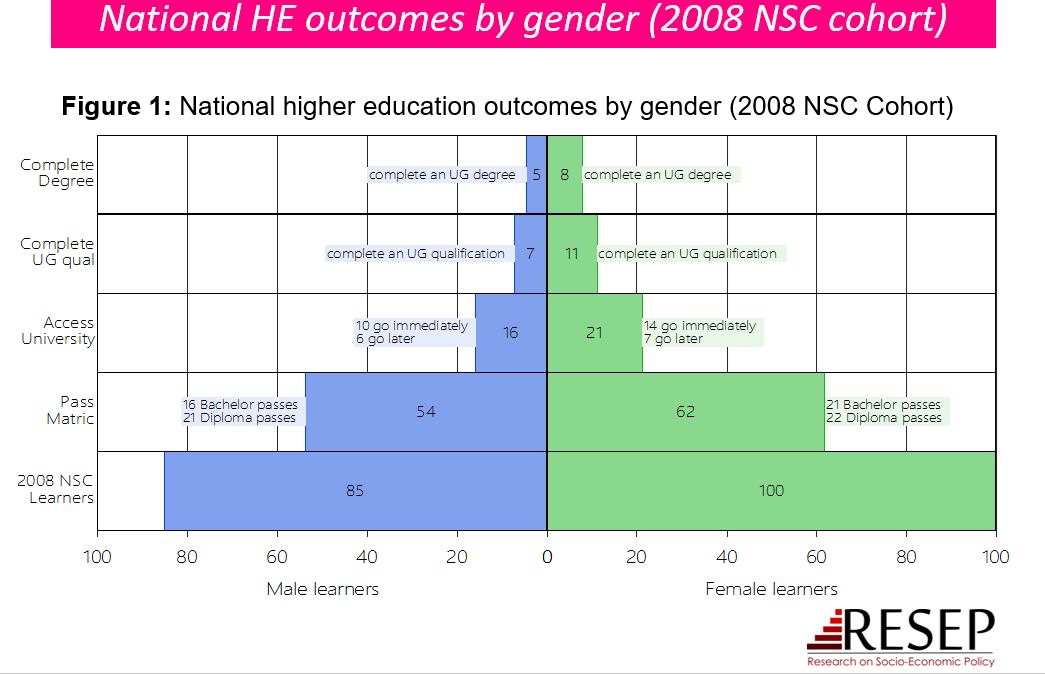

You may have heard of the “Matthew effect,” in which those who are performing well tend to continue to get better off. Spaull presented on the “Martha effect,” or how superior female performance in South African high schools continues into higher education. Strikingly, while females are less likely to enter certain fields (engineering, math), they often are more likely to complete them if they do enter. You can read the paper here. |

|

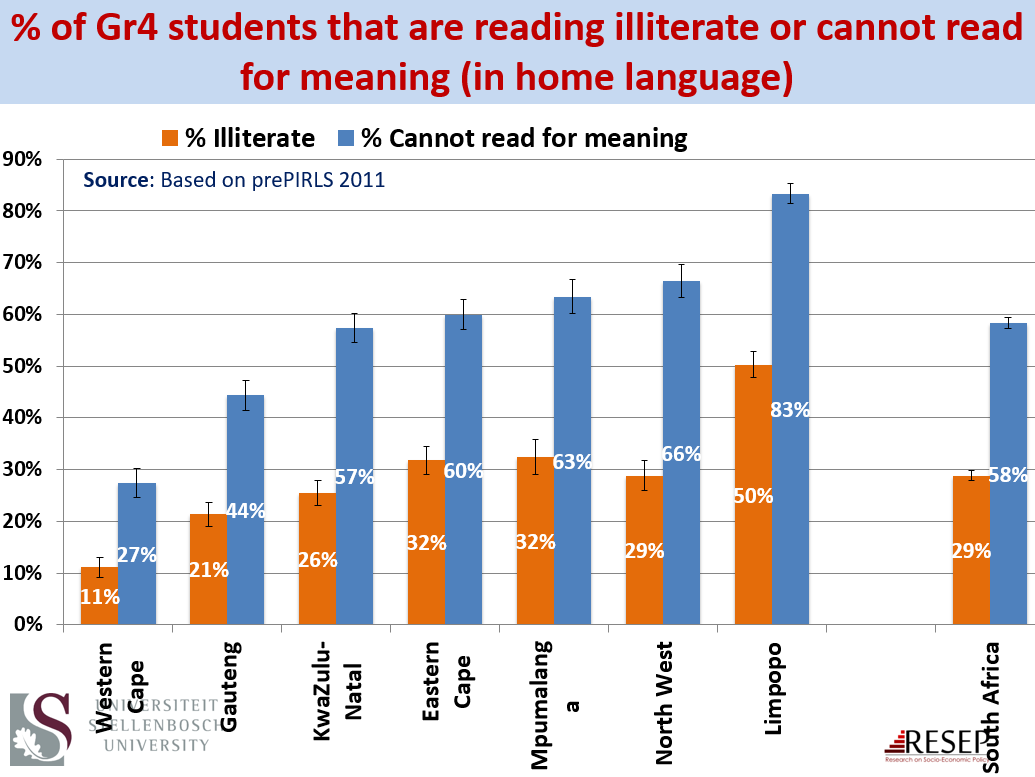

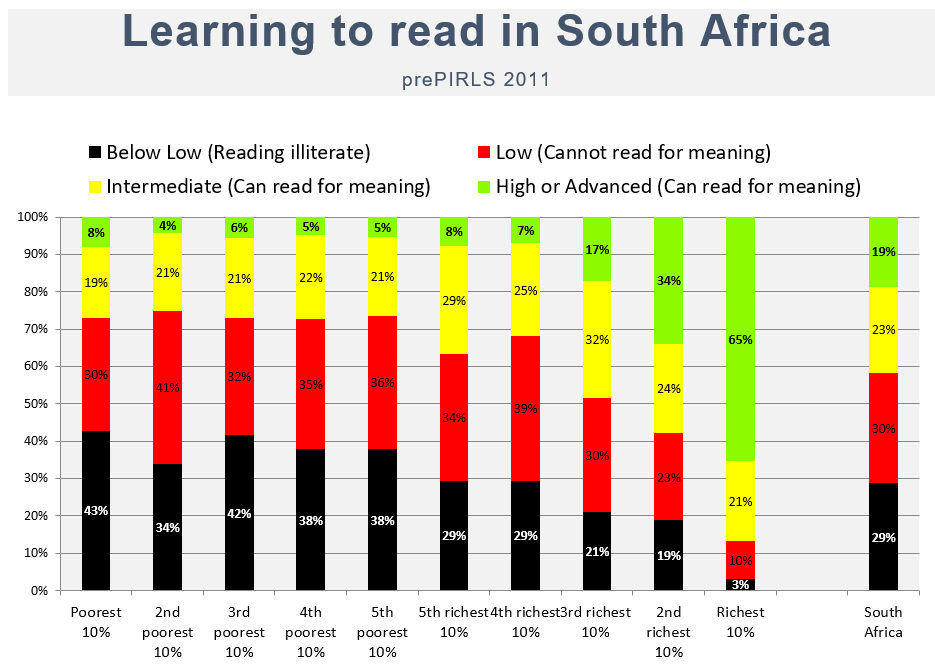

During a panel discussion, Spaull highlighted inequalities in learning in Grade 4 in South Africa. |

|

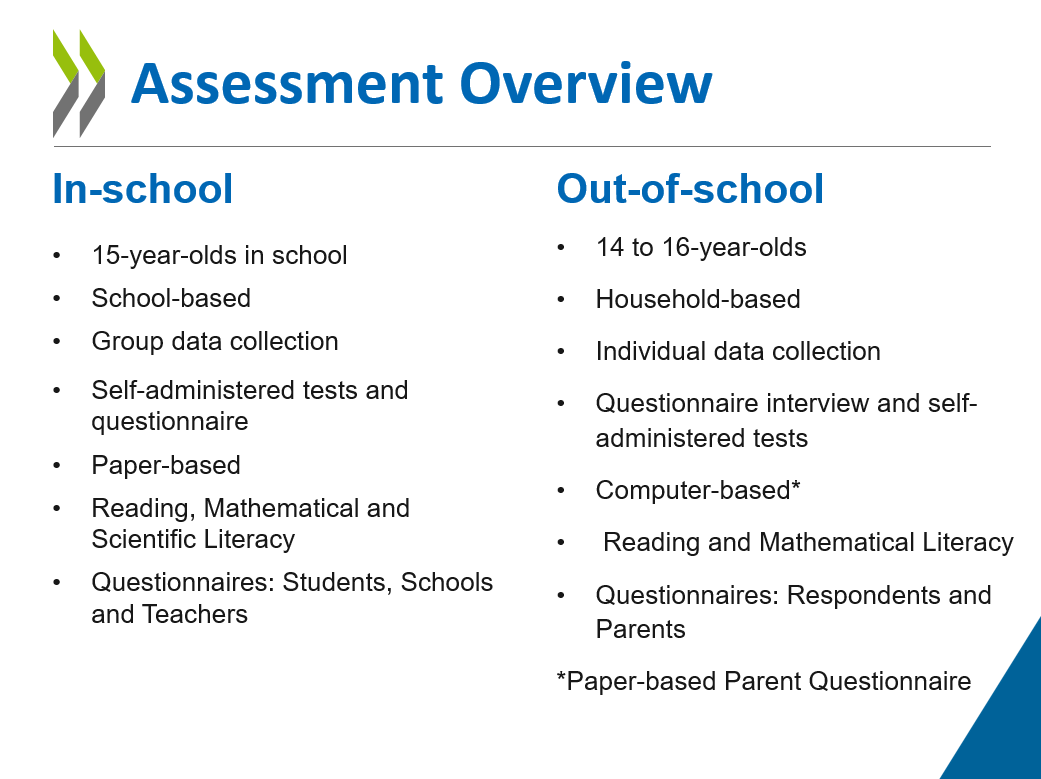

PISA provides useful cross-country benchmarks on learning, but how useful is it when many 15-year-olds are out of school, or when most of the tested population is in the lowest performing group? Belfali presented on “experiences from PISA for development,” which seeks to incorporate out-of-school children and gather more data relevant in low-income environments. You can read more about PISA for Development here. |

|

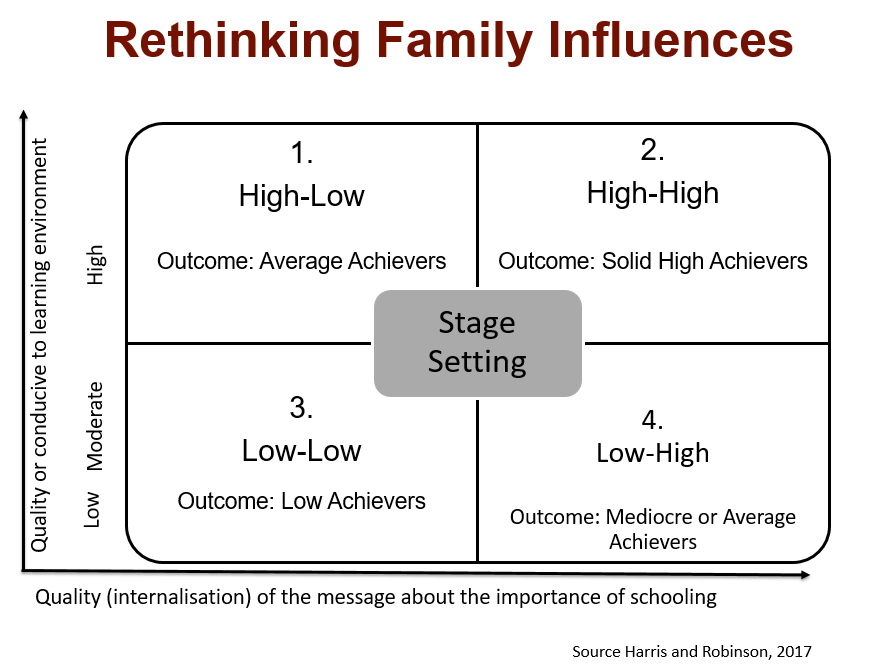

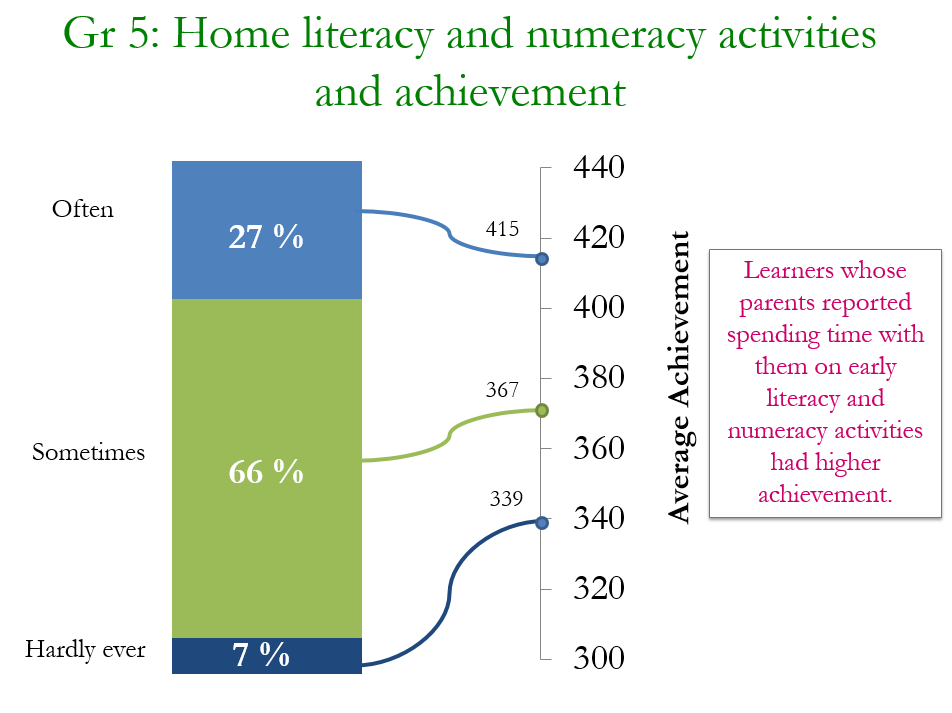

Zuze provided a framework for re-thinking parental influences on learning outcomes and provided evidence from South Africa’s Early Grade Reading Study. |

|

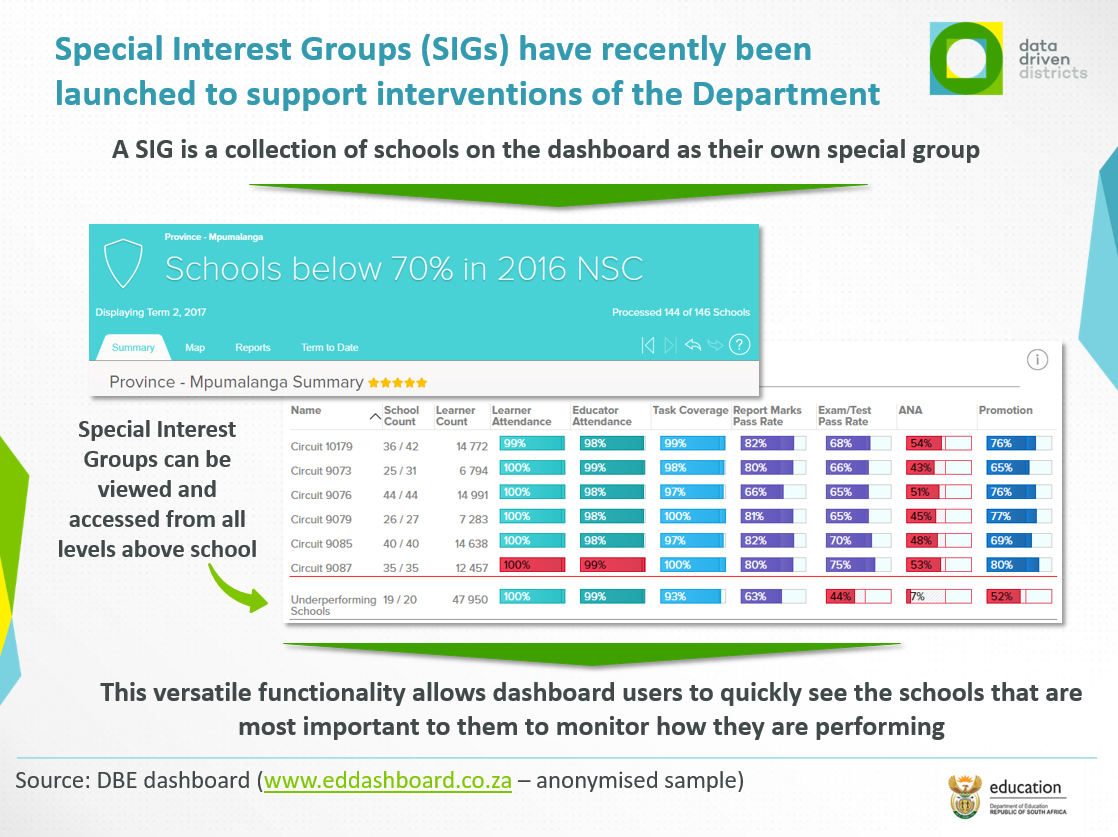

Gilette showcased an effort to provide real-time, actionable data to education administrators to improve school performance. |

|

How do teachers help students to do better? Kanjee presented evidence on the kinds of feedback that teachers give students, and an effort to improve the quality of that feedback. |

|

Reddy demonstrated a wide range of gradients in learning across home environments and types of schools in South Africa. |

South Africa clearly has a rich, ongoing research program regarding education. Part of the reason that’s possible is that South Africa collects data on learning at multiple stages throughout the schooling process and makes it public. The World Development Report 2018 demonstrates that many countries don’t do this, as the figure below shows. Of course, “weighing a pig doesn’t make it fatter”: Measurement by itself doesn’t solve problems. But measurement can be a first step in identifying general and specific challenges and can be one ingredient in galvanizing public support for reform.

Source: World Development Report 2018

Join the Conversation