Many researchers hope that their research will have some impact on policy. Research can impact policy directly: A policymaker uses the results of your study in making a policy decision. For direct policy impact, policymakers – or the people who advise them or the people who vote for them – have to know about your work. Research can also impact policy indirectly: Your research becomes part of a body of evidence which collectively affects future policy decisions. For indirect policy impact, other researchers have to know about your work. It is unlikely that your research will impact policy either directly or indirectly if no one knows about it.

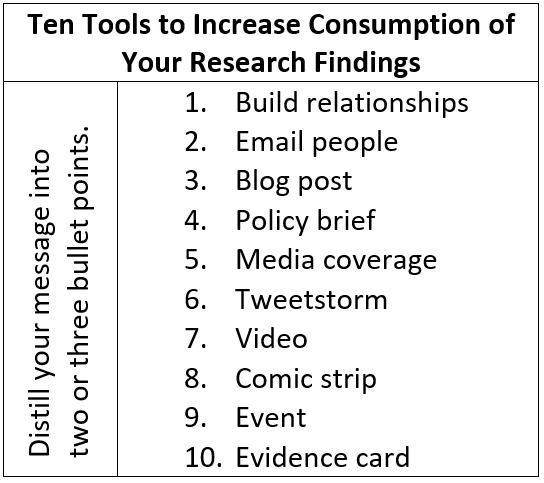

Over the years, I’ve experimented with many ways of increasing consumption of research (together with colleagues and co-authors), and I’ve seen many other ways. Here is a menu of ten options. The point isn’t to do all of these, but rather to select those that will help you reach the audience you most want to impact.

Before the ten tools, here’s an underlying strategy, crucial for all of these tools:

Distill your message into two or three bullet points. I get it. Your message is nuanced. But if it’s impossible to explain the take-away with brevity, the chances you’ll be able to communicate it effectively to people outside your field are very low. The chances that anyone will remember are even lower.

Even longer communication forms, like blog posts or policy briefs, work best when they can be boiled down to a few quick points. Sometimes those points are different for different audiences. In recent research I did with Mũthoni Ngatia, we had two big messages, one about long-term impacts of education interventions, and one about school uniform policy. We wrote two separate blog posts, each focusing on one of those messages. But in both cases, we distilled the findings to a couple of sound bites (er, word bites) we wanted readers to take away.

And now, 10 tools I’ve experimented with to increase consumption of research!

1. Build relationships. Relationships between researchers and policymakers are one of the biggest predictors of policymakers using research. There are lots of ways to invest in these relationships, including lots of briefing meetings, supporting policymakers in work beyond the results of your research, and co-generating questions. If you’re an international researcher, partner with local researchers who have those policy links (in addition to everything else they bring to the table).

2. Email people about your findings. Make a list of people that you want to be sure see your paper – academics, policy makers, journalists, thought leaders, whoever you want to make sure sees these results. I have a template that I use to prompt me when thinking of who to share my paper with. Then I send them the paper with a short explanation of why I think it might be of interest to them. I usually include the title and abstract in the body of the email, and I both attach the paper and link to it. If I’ve written short versions of the paper (e.g., blog posts), I include links to those as well. If there are a few specific people that I’d really like to see my paper, I send it to them via email.

3. Write a blog post. A blog post presents an opportunity for you to discuss your motivation and your results. For me, these work best when they’re less technical than the paper and much, much shorter. The objective is not to go through every result and every robustness check, but to focus on the big message. What are the one or two things you’d most like people to take away from your paper, and what’s the least technical level of evidence you can use to convince most readers? Link to your paper for the technical details. McKenzie and Özler published evidence that blog mentions increase abstract views and downloads of research papers.

If you have access to an established blog, that’s a natural venue. I publish most blog posts about my research here at Development Impact, such as Monday’s post on measuring educational impacts for vulnerable groups or this earlier post on cash transfers and trust in local government.

Otherwise you can pitch a piece to a site like VoxDev – here’s a piece I had accepted there on healthcare in Nigeria, or an occasional blog like Economics that Really Matters.

But once you write a blog post, it’s not automatic that people will read it: I tweet and email and Facebook post about blog posts that I believe may be of interest to readers.

4. Write a policy brief. Almost every dissemination plan I see mentions a policy brief – a short, non-technical version of the paper intended for policymakers and their teams. There are many different models, as I’ve outlined before. I find many to be too long or too text-heavy: I believe that someone who is willing to scan 6 pages of text may be almost as likely to scan your paper. But that’s just my personal preference; I haven’t seen a lot of evidence on this.

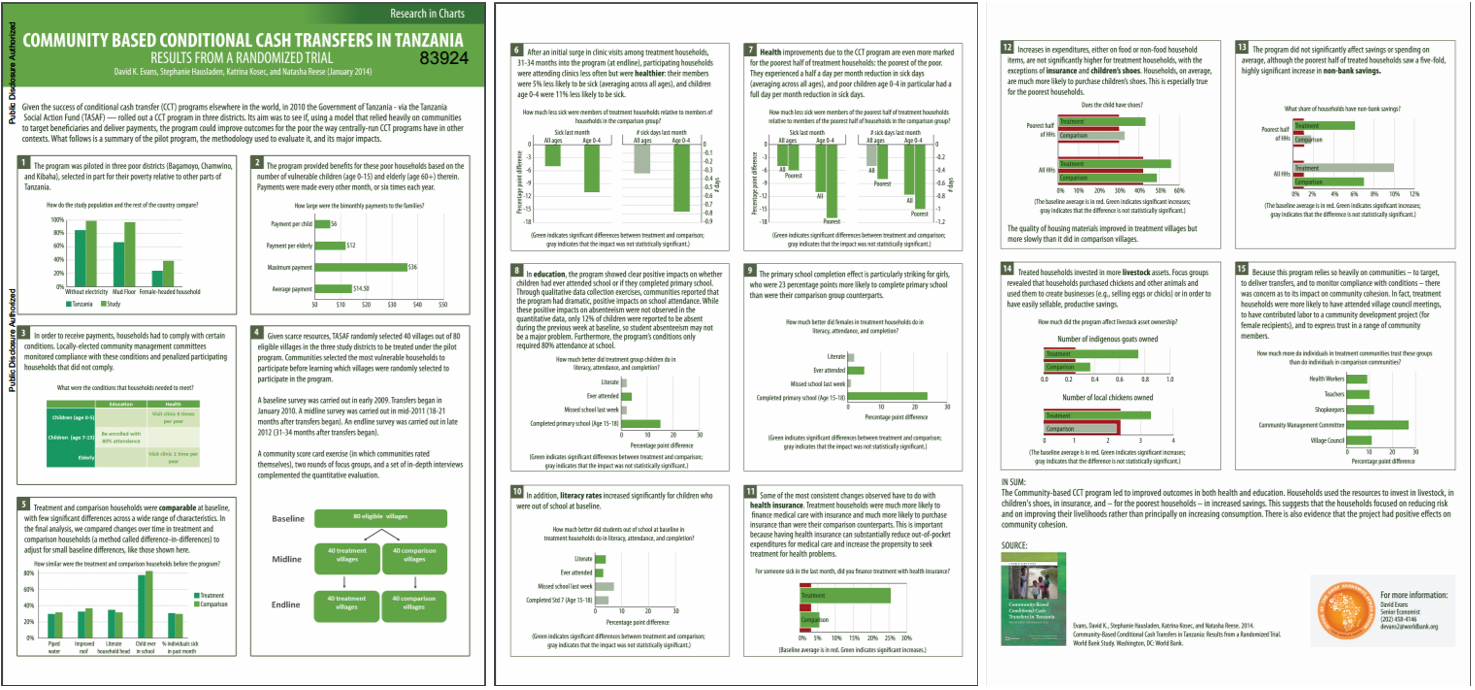

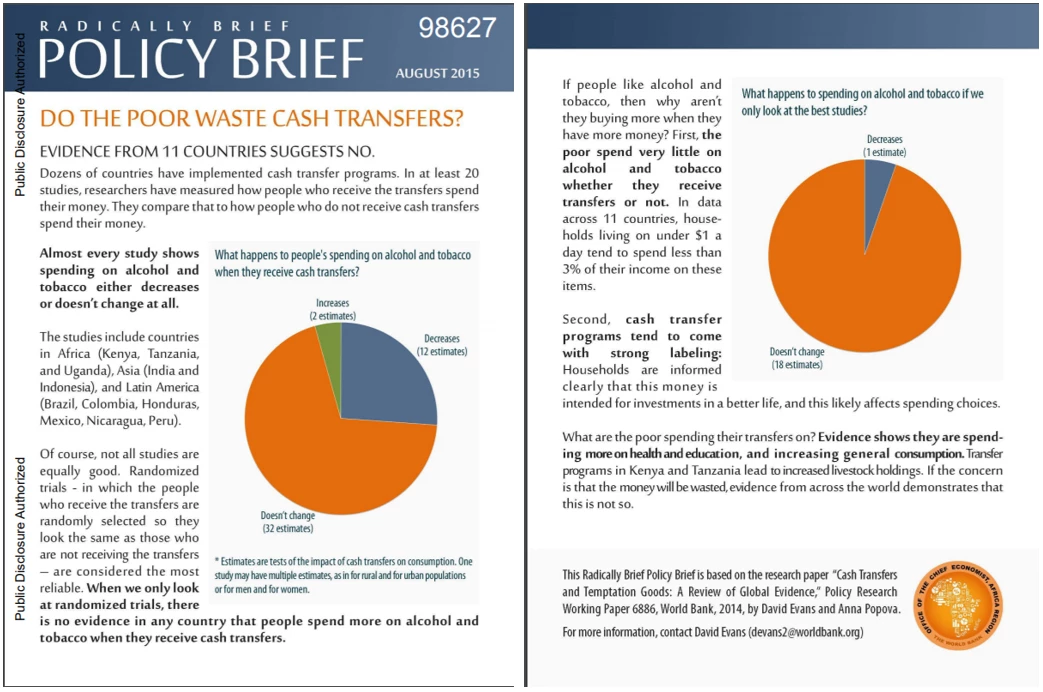

Don’t be afraid to experiment with the form. Colleagues and I started a series called the Radically Brief Policy Briefs, which were just one three-quarter size sheet, front and back, with a couple of analytical images, as you can see below.

Here’s another example: A few years ago, co-authors and colleagues and I prepared a policy brief on cash transfers in Tanzania where every point was supported by a figure, which we called Research in Charts. I handed some out at a workshop in Rwanda, and the next day, on a flight from Rwanda to Tanzania, I noticed government officials reading it. Success! (Well, minor, intermediate success! Still!)

5. Get media coverage – even if you write it yourself. If you do your research in India, consider pitching an op-ed to an Indian newspaper, like this one on air pollution or this one on a housing project in India. These researchers published an op-ed on Kenyan HIV research in Kenya’s Daily Nation. Or if you have media contacts, you can try to get a local reporter to cover your work. Obviously written media is just one way to reach people. Alice Evans has gotten local TV coverage of her research in Zambia.

You can also seek coverage in non-local news sources, either written by yourself or others. Quartz covered Emma Riley’s work on aspirational entertainment in Uganda as well as my work with Popova on cash transfers and spending on temptation goods. Jayachandran and Pande have written about their India-focused work on child height in the New York Times.

6. Make a tweetstorm. Even shorter than most blog posts is the tweetstorm, where you describe your paper over a series of tweets, each a reply to the last (so they’re connected). My favorite tweetstorms use figures or tables from the paper to tell the story, like this one from Jayachandran on her work with Jack on payments for environmental conservation in Uganda. They’re a quick way to give Twitter readers your message. Why not just write a blog and link to it in a tweet? I believe that every time you ask someone to click a link, you lose readers. So if you can put the content right there, do it.

I occasionally do a playful tweetstorm of a paper, where each of the tweets has a humorous image or clip associated with it. Here’s one on how to measure patient satisfaction more effectively. I don’t expect these funny threads to convince a Ministry of Finance, but I believe they can catch the eye of the impatient scroller on twitter.

7. Film a video. A lot of people would prefer you just explain your research to them, rather than actually having to READ SOMETHING. A few months ago I made a video describing the results of my work (with Holtemeyer and Kosec) on cash transfers in Tanzania in 90 seconds. I made it on my phone, and the entire process took less than an hour. Of course, you can probably tell that from the bare bones production. But quite a few people responded favorably on twitter, where I posted it directly. Alice Evans has made several of these, and gives advice on what makes a good one.

Here’s a nice example with Nick Bloom talking about his research on a management intervention in India.

There are more examples here. With my 90 second video, I posted it directly on Twitter and on Facebook as well as posting it on Youtube.

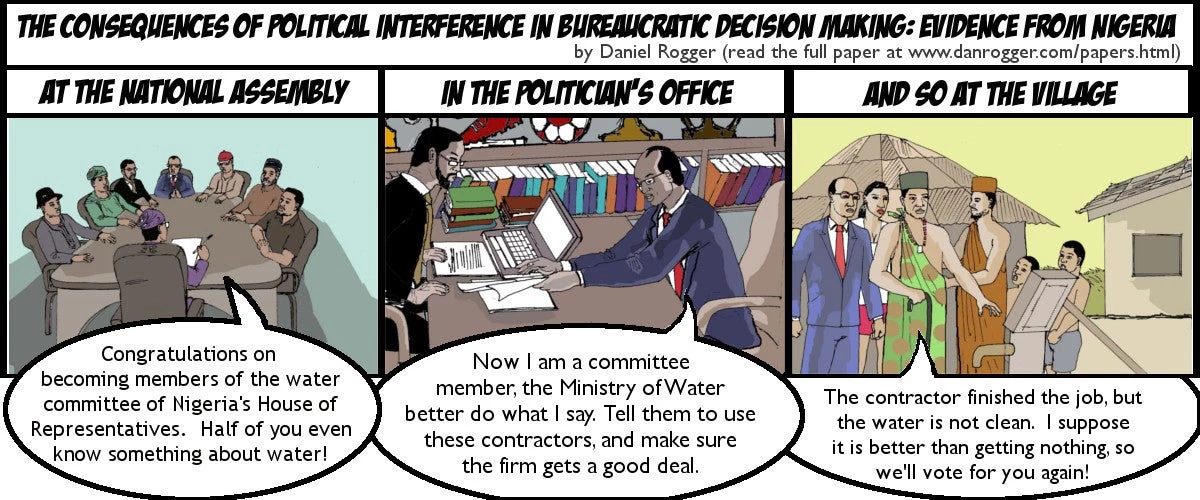

8. Draw a comic strip. Or have someone else draw a comic strip. Dan Rogger has a paper on politics and infrastructure projects in Nigeria and commissioned the comic strip below to capture the major point of the paper.

Lucy Lambe provides more examples of using comics to communicate research findings.

9. Hold an event. Of course, you can put together a panel of experts (including yourself), with policymakers reacting as to the relevance of the research to their decisions. In addition, I’ve experimented with debates (called Smackdowns!) where I invite researchers to tell operational teams how their operations are ignoring key evidence, and at the same time I invite operational teams to tell researchers how their research isn’t answering the key questions to improving services for the poor. It’s all done in a good spirit, and the conversations have been refreshing. I’ve also co-organized more traditional debates, seeking to provide a lively discussion of evidence around a key issue. (Here’s one you can watch, on private education in Africa. You have to scroll to the third video on the list.)

10. Make an evidence card. Remember at the beginning, when I talked about distilling your message to a few key ideas? For a few events, colleagues and I helped researchers to do just that and then put the messages on a card (the size of a business card, literally) so that people could take away the messages and remember them at a moment’s notice. The example below is from a paper by Campos et al.

Obviously, it might not make sense to do all of these for every research paper. But if it’s worth doing the research, it’s worth making an effort to ensure that people see it and learn from it. So, make your research known!

Bonus reading

- Jishnu Das on why you might want your research to have LESS (direct) impact on policy.

- Especially with indirect impacts, we often don’t know what the impact is. Consider the words of Rebecca Solnit: “You don’t know if your actions are futile; that you don’t have the memory of the future; that the future is indeed dark, which is the best thing it could be; and that, in the end, we always act in the dark. The effects of your actions may unfold in ways you cannot foresee or even imagine. They may unfold long after your death. That is when the words of so many writers often resonate most. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.” True! But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth making some effort to have an effect that you can observe.

- Several of these ideas were developed in collaboration with Mapi Buitano and Beatrice Berman of the World Bank. They're amazing.

Oh, and in case you’re still reading, here’s a summary sheet of this blog post.

Join the Conversation