This is the eighteenth in this year's series of posts by PhD students on the job market.

In 2012, 700 million people in India suddenly found themselves without power for over 10 hours. At the time of the incident, political parties blamed each other for mismanagement and failing infrastructure. Such incidents reflect the extensive dysfunction in the sector, with technical problems and billing leakages that are among the worst in the world, amounting to 20% of electricity generated. The poor quality of electricity supply imposes major costs on the Indian economy; electricity shortages, for example, reduce manufacturing plant revenues by 5-10%. Why do these problems persist despite exponentially growing power generation? My job market paper shows that political corruption is one of the root causes behind unreliable electricity supply.

What is the link between political corruption and poor electricity supply? In democracies, incumbent politicians may consolidate power by favoring their voters with better access or lower prices. In India’s electricity sector, where politicians do not have direct control over electricity pricing, they may resort to illicit means in order to do this. Lower prices may actually benefit targeted consumers. But such patronage is costly: it hurts the revenues of electricity providers, inhibiting their ability to invest in infrastructure, and lowering electricity reliability for all consumers. While subsidies and increased access benefit consumers in targeted constituencies, the resulting underinvestment by providers may lead to unreliable supply.

Estimating the often-ambiguous welfare implications of corruption is, therefore, a challenge. Especially since detecting corruption is hard: corruption is frequently concealed, complicating the task of making causal inferences and identifying mechanisms of corruption. In this research, I develop novel methods to address these challenges, and find that political corruption in the electricity sector leads to large revenue losses for electricity providers, worsening their ability to reliably provide electricity.

1. Detecting Corruption

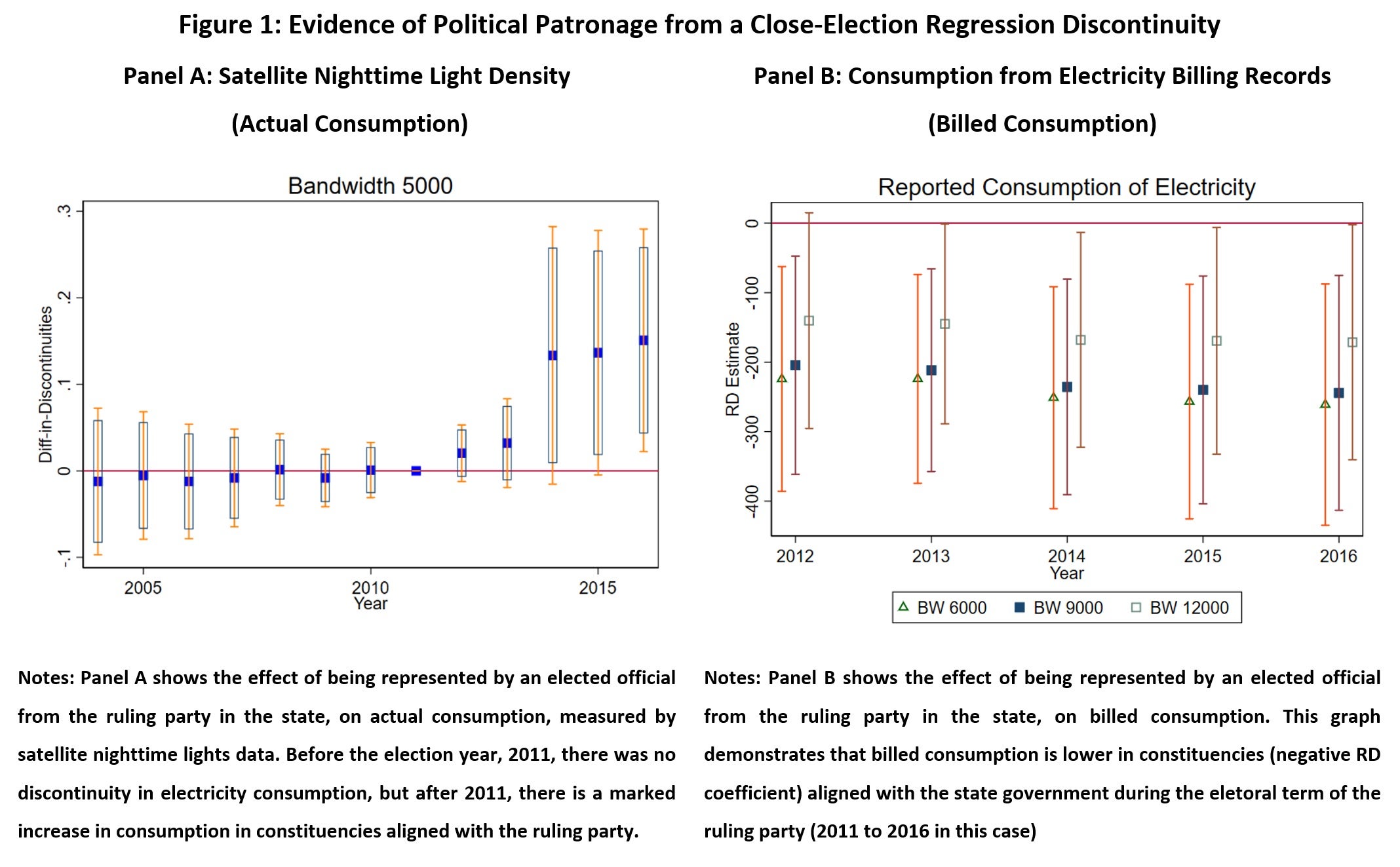

Leveraging a close election Regression Discontinuity (RD) design from West Bengal, India, I show that regions aligned with the governing party are rewarded with illicit electricity subsidies. I find that shortly after a state-level election, there is an increase in actual electricity consumption, as measured by satellite nighttime lights data, for regions that voted for the winning party in the state government (Figure 1, panel A). Alone, this evidence appears to indicate selectively higher electricity access for these regions, possibly owing to politicians redirecting electricity distribution. However, constituencies of the ruling party have discontinuously lower levels of billed consumption (Figure 1, panel B). Being one of the few studies to have novel consumer-level billing data, spanning over 17 million accounts and several consumer categories including residential and commercial, such evidence has not been highlighted before.

The conflicting patterns of electricity consumption are consistent with the systematic under-reporting of billed consumption in targeted constituencies, effectively constituting an indirect subsidy. And, the magnitude of under-reporting is large, constituting a discount greater than 40% of billed consumption for consumers at the RD cutoff.

Previous work relied on satellite nighttime lights or aggregated data to show suggestive evidence that politicians increase electricity supply before elections, to sway voters. However, these data alone cannot distinguish between a reduction in provider revenue, which has significant implications for investment, and a simple reallocation of electricity from regions supporting the opposition to those aligned with the ruling party.

Given the magnitude of underreporting, is it any surprise that the combined leakages from under-collection of bills, electricity theft and poor infrastructure in West Bengal was as high as 28% of electricity generated?

2. Mechanisms of Corruption

To address the revenue-draining patronage that undermines electricity provision in India, we must understand how this patronage is practiced.

Using the close-election RD framework, I find selective data manipulation in the ruling party's constituencies. I test for manipulation using two measures. First, examining the consumption distribution of each electoral region, I observe that a discontinuously higher number of bills in the winning party's constituencies are multiples of ten, reporting consumption amounts such as 20, 30, and 40 units. This is consistent with data-tampering to lower the billed consumption of accounts in the ruling party’s constituencies. I confirm this with a measure based on Benford’s Law, which is commonly used to detect fraud in surveys, elections, and other contexts. This measure also shows a greater magnitude of manipulation in areas where the ruling party won local elections.

In a context where electricity meter inspectors have poor incentives to conduct meter readings, and accurately record electricity consumption, there is opportunity for local billing centers to manipulate the consumption data downwards. These billing centers are under the purview of the locally elected representative, or Member of Legislative Assembly, who holds a lot of power.

3. The Welfare Implications of Corrupt Practices

After finding evidence of political corruption in electricity billing, the question now is – what effect does this have on overall welfare? The magnitudes of the welfare gains to consumers and the deadweight loss determine the distributive consequences and policy urgency of the corruption problem.

To identify the welfare implications on each of the parties involved, I measure both the gains to consumers from receiving subsidized electricity and the lost revenue to the provider due to under-reported bills. I estimate the size of the loss in producer surplus from RD estimates of bill misreporting.

Estimating the increase in consumer surplus requires computing the price elasticity of electricity demand, which is made difficult by bill manipulation; therefore, I develop a method for calculating price elasticities of electricity demand in the presence of data manipulation. I first divide the data into two sets -- the set of regions where the data are plausibly unmanipulated by political influence, and the set that contains underreported bills. Manipulated data were far more likely to be in winning party constituencies, but there was manipulated data in other constituencies as well. Similarly, unmanipulated data were seen in both winning and losing party regions. . I estimate the price elasticity of electricity demand for the regions with unmanipulated data by taking exogenous, policy-determined variation in electricity prices (as set by independent regulators) as instrumental variables. I then use machine learning methods to predict elasticities for all regions, including those where data is manipulated.

Using the estimated underreporting in consumption, and the elasticity estimates, I find that losses of producer surplus are more than double the gain in consumer surplus for regions near the RD cutoff. Simple calculations show that the net welfare loss is sufficient to power 3.7 million rural households.

4. The Implications for Policy

In theory, politicians may be able to target basic services to their voters who need it the most, increasing their consumer surplus. Indeed, democracy could play an important role in ensuring the efficient allocation of government inputs in an effort to garner votes. However, it could also result in misallocation, electoral cycles and preferential access – as I find in this case. These distortions exacerbate the already poor quality of electricity supply.

This is particularly relevant as we move towards a future with renewable sources of power, which have large fixed costs. Corruption may deter private players from providing these technologies. My paper underlines the importance of transparency in electricity provision. For instance, universal smart metering would eliminate middle men (meter readers) who enable corruption to occur. Smart meters are often expensive; however given the large deadweight losses from corruption, they may be justifiable. Similarly, shifting away from increasing block prices in electricity would make it easier for consumers and auditors alike to detect anomalies in billing. These steps would make the system more transparent and are policy actions to explore in the future.

Meera Mahadevan is a PhD student at the University of Michigan working on Development and Environmental/Energy Economics.

Join the Conversation