This is the 21st and final post in our series of posts by PhD students on the job market

“In life, two things are certain: death and taxes, the saying goes. Unless you are a large multinational corporation, in which case, maybe not.” This may sound like political banter to you, but it is not: it is a quote from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Multilateral institutions are heavily involved in improving tax enforcement: the World Bank recognizes that “mobilizing tax revenue is key” for developing countries to end extreme poverty by 2030.

In my job market paper, co-authored with Felipe Lobel (UC Berkeley) and Pedro Zúniga (Servicio de Administracion de Rentas), I partner with the tax authority in Honduras to study the impacts of a policy aimed at increasing tax collection from corporations: minimum taxes. Corporate income taxes are usually assessed on declared profits – gross revenue net of costs incurred in the production process. There is ample evidence, however, that firms overreport their true costs to minimize their tax bills. Minimum taxes seek to assure that large firms will not avoid taxation: in the case of Honduras, firms declaring yearly revenue above L10 million (approximately USD 400,000) must pay the largest value between 25% of their declared profits and 1.5% of their gross revenue. For these large firms (approximately the top 20% in terms of revenue), reporting low profits cannot reduce their tax bill.

While minimum taxes similar to this one are used across the world and recommended by the IMF, evidence on their impact on tax collection and the behavior of firms is still scarce (Best, Brockmeyer, Kleven, Spinnewijn, & Waseem, 2015; Alejos, 2017; Mosberger, 2016). My paper contributes new evidence that can inform the design of these policies.

Under profit taxation, firms overreport costs to evade taxes

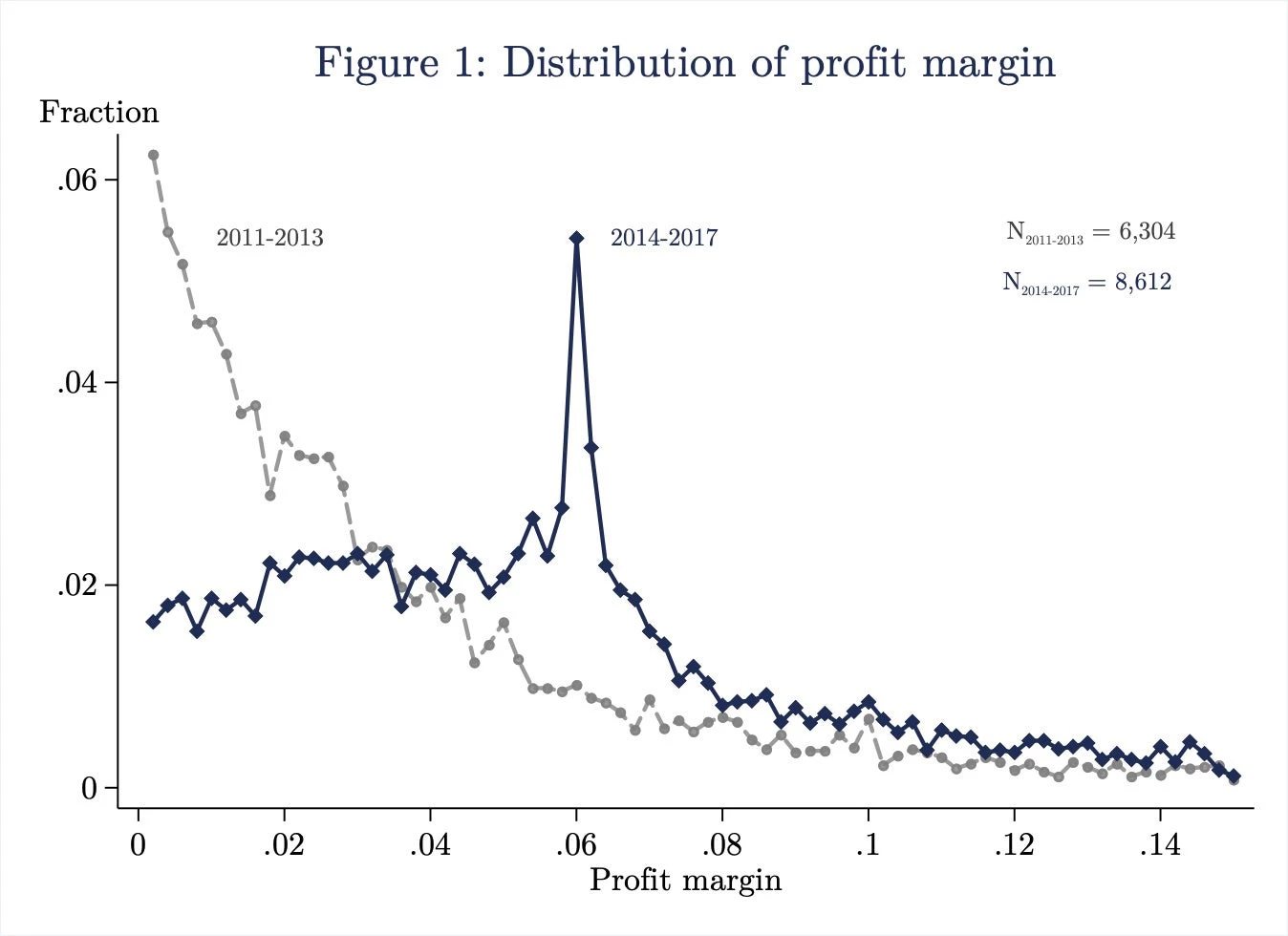

The immediate objective of the minimum tax policy was to create a floor to how much taxes large corporations pay: regardless of declared profits, firms with revenue above L10 million should pay no less than 1.5% of their declared gross revenues in taxes. That implies firms could no longer reduce their tax bill by overreporting costs and claiming low profits. In my first set of results, summarized in Figure 1, I show that taxpayers reacted to the introduction of the minimum tax by substantially increasing their reported profits. In 2011-2013, before the minimum tax was in place, a large share of taxpayers declared profit margins close to zero. When the incentives to overreport costs disappear in 2014, this behavior immediately changes: corporations start reporting much higher profits, as seen by the shift of the profit margin distribution to the right. This is clear evidence that corporations were evading taxes through cost overreporting. I quantify this evasion response and estimate that under profit taxation firms were increasing claimed costs by as much as 17% of profits in order to decrease taxes. This is similar to estimates from corporations in Pakistan, for example.

Corporate tax filings are complex documents and firms can claim over 100 different types of costs separately. One relevant policy question arising from these evasion responses is whether some cost items are particularly prone to evasion. I show that to be the case: I observe no response in cost items that are easily traceable, such as labor and financial costs, but strong responses in hard-to-verify items linked to costs of goods and materials, like inventories. This suggests specific cost items that can be the focal point of government audits.

If you tax revenues, taxpayers report less of it

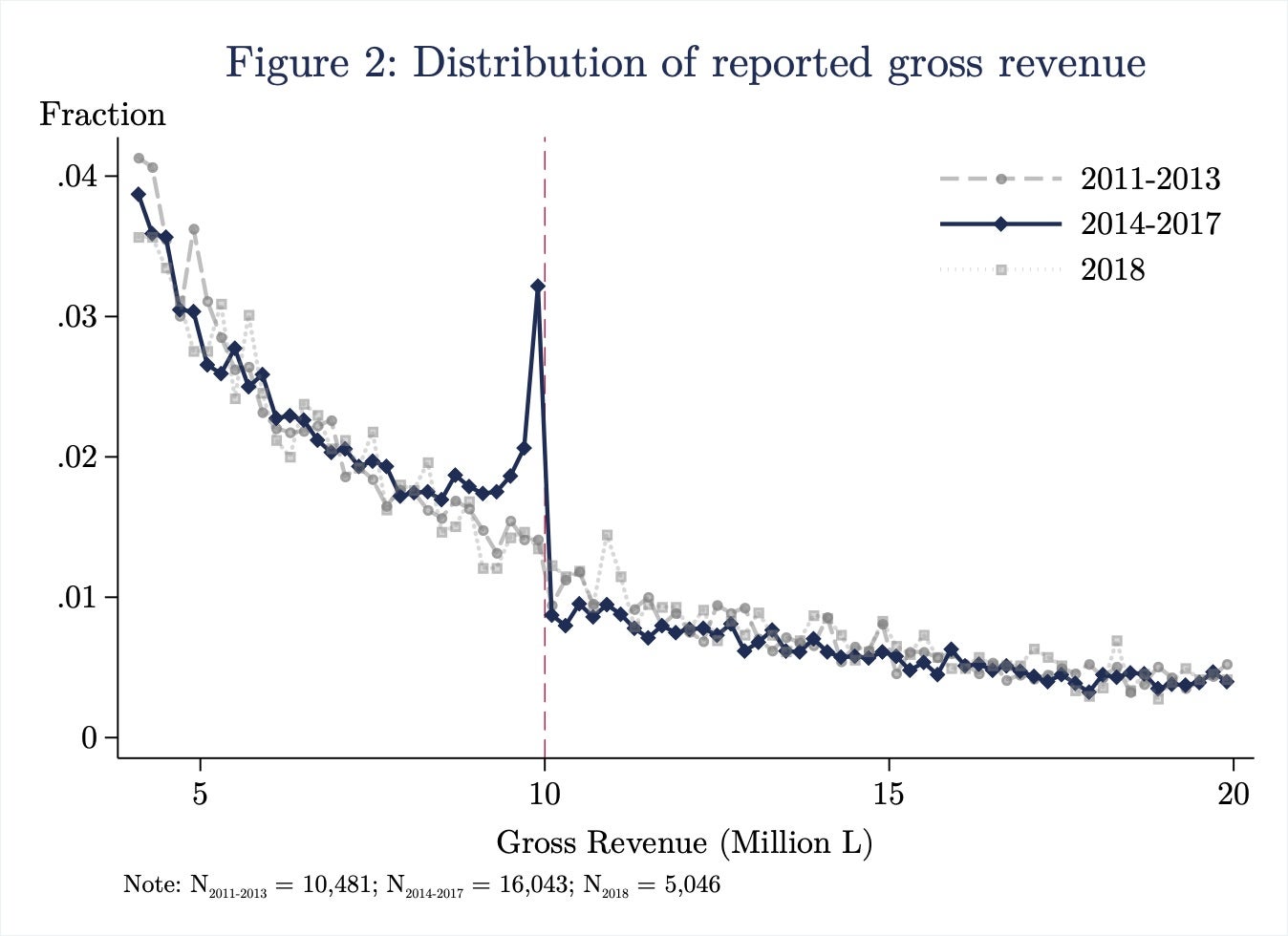

My second set of results relates to how firms change their reported revenue when facing higher taxes. Recall that firms declaring gross revenue below L10 million are exempt from the minimum tax. This creates a threshold where tax liability might change discontinuously in response to small changes in declared revenue. As an illustration, a firm declaring L9.99 million in revenue and close to zero profits will pay virtually no taxes (they are taxed on declared profits) but declaring L10 million would generate a tax liability of L150,000 (1.5%*L10 million) under the minimum tax. This generates strong incentives for firms to strategically locate below the exemption threshold.

I show that firms do precisely that. We observe an excess number of firms declaring revenue slightly below L10 million while that was the exemption threshold. As shown in Figure 2, those “bunchers” (taxpayers reducing revenue to avoid the minimum tax) are not there before the introduction of the minimum tax (2011 – 2013) nor after the exemption level is substantially raised in 2018. I use tools from the bunching literature to quantify how declared revenue changes in face of changes in the tax rate, i.e. to determine the elasticity of reported revenue. I determine this elasticity to fall in the range of [0.35, 1]. These estimates are meaningfully higher than previous findings in other contexts, such as Costa Rica. This illustrates the limits faced by tax authorities in increasing tax collection under the existing enforcement environment: increasing tax rates leads to significant decrease in the declared tax base.

This decrease in reported revenue is partially explained by firms misreporting their earnings. I construct firm-level measures of revenue observability, defined as the share of self-declared revenue that is independently observed by the tax authority through third-party reporting. I show that firms with high revenue observability are much less likely to strategically locate below the exemption threshold. I also show that the same pattern holds across industries. In industries where revenue is more often independently assessed by the tax authority, such as manufacturing, we see much less bunching below the exemption threshold and lower implied revenue elasticity. Having better information on taxpayers’ revenue seems to attenuate their misreporting behavior.

Policy implications

What should policymakers and citizens more broadly take from our study? First, documenting widespread tax evasion is a first step to garner political support for policies that assure corporations pay their fair share – political engagement is key for enacting the right policies. Second, policymakers and multilateral organizations should recognize that the response of taxpayers to different policies is not immutable but depends on the enforcement environment. In the case of Honduras, improving third-party information on taxpayers’ revenue would make the minimum tax more attractive since reported revenue would decrease by less. More broadly, our results are consistent with other recent evidence that investments in the capacity of tax authorities might generate large gains in revenue by curbing evasion.

Thiago Scot is a PhD candidate at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business

Join the Conversation