or, why we need more systematic (and simply more) reporting on the nature of interventions

The hope. Last year, we reviewed six reviews of what interventions work to improve learning. One promising area of overlap across reviews had to do with training teachers who were already on the job (i.e., in-service teacher training or teacher professional development). Specifically, we proposed that “individualized, repeated teacher training, associated with a specific method of task” was associated with learning gains.

Now if you know anything about in-service teacher training as it’s practiced in many countries, you might say, “What?! There’s no way that’s effective.” Many – including both of us – have the intuition that much of in-service teacher training – one-time workshops or general pedagogical training – does little to help teachers actually improve their classroom practice. But we aren’t talking about any old teacher training here: Again, we’re talking about very specific forms.

Specifically, consider a program that trained teachers and gave them regular mentoring to put in place early grade reading instruction in local language and led to significant learning gains in Uganda (albeit not in Kenya). Or consider a program in India that gave contract teachers two weeks of training and reinforcement throughout the year and led to significant gains. Or other programs in Chile, Uganda, and India.

The counterpoint. Yet for all these programs, there are other teacher training programs that failed. A program in Uganda that worked well when implemented by an NGO actually had some negative effects when implemented with government trainers. A three-month English training program for teachers in China had no impact on student English scores, probably because it also had no impact on teacher English scores. At the same time, serious budget resources go into teacher professional development: Over 13 years, nearly two-thirds of World Bank education projects had teacher professional development components, and those resources are a drop in the bucket relative to national expenditures.

A new paper to get some answers. So there are some winners and losers in training programs: What explains it? In a new paper written together with Violeta Arancibia, we tried to dig into these programs. After all, ten teacher training programs usually means ten different models – one program trains off-and-on throughout the year, another trains for two weeks during the holidays; one trains teachers in subject knowledge and another in pedagogy. Do some of these characteristics predict which programs work well? We decided to search for impact evaluations of teacher training programs with student learning outcomes, categorize the programs by their essential characteristics, and see which (if any) of those characteristics were associated with learning gains.

A new instrument. But what characteristics should we measure? We searched for a survey instrument for characterizing the nature of teacher training programs and came up high and dry. We found instruments for teacher policy (SABER Teachers) and instruments for classroom observation (CLASS and Stallings, for example), but nothing in between, to characterize the actual training teachers receive that should supposedly help them do better in the classroom. So, through repeated consultations with a range of education experts and consulting the literature, we constructed a new instrument – the in-service teacher training survey instrument (ITTSI), available in Appendix B of our paper. (We haven’t yet come up with the BITTSI or the SPIDER instruments. Coming soon, though.) The instrument asks 70 total questions about (1) overarching program aspects, (2) program content, (3) delivery mechanisms, and (4) perceptions of program effectiveness by program implementers. For example, it asks who delivers the training, what the focus of the training is, which activities it includes, how many hours it takes and how many of these are spent practicing, whether there are in-school follow-up visits, whether various materials are provided alongside the training, whether there are professional implications to participation (e.g., doing great in the training gets you a promotion), and the like.

What we know from rich countries. We examined whether this question had already been answered in high-income countries. Short answer: No. In Fryer’s recent meta-analysis of 196 randomized field experiments in the U.S., he does find that “managed professional development” (which focuses on specific pedagogical techniques) leads to much higher gains than “general professional development” (which focuses on more general pedagogical skills, not applied to a particular subject). But he only found 2 RCTs on the former and 7 on the latter. Much other evidence from rich countries is qualitative. Tellingly, one study of mathematics professional development programs concludes – after reviewing 910 studies and finding only 5 of high quality – that “the limited research on effectiveness means that schools and districts cannot use evidence of effectiveness alone to narrow their choice.” (Cue the sad trombone.)

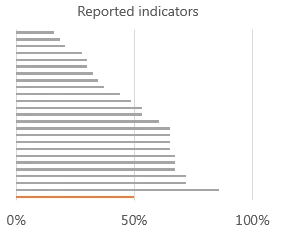

A few dozen evaluations but a lack of data. We searched and identified 23 impact evaluations of 26 primary education interventions in low- and middle-income countries that either focused on in-service teacher training, or included this as one component of a broader program. Then we applied our instrument to those 26 programs. We found that the median program reported only half of the indicators in the impact evaluation, per the image below.

It’s hard to get a clear picture of what kinds of programs work when you don’t know what the programs even look like. So we tried to track down the implementers of the programs and interview them. We managed to speak with implementers for 12 of the 26 programs. Once we spoke with the implementers, we were able to fill in virtually all the indicators. So it’s not that the instrument is unreasonable: These data exist. They’re just not reported.

Do the program characteristics predict success? With just 26 observations, we’re hesitant to draw strong conclusions; there just isn’t much statistical power there. The real take away is that we need to report more consistently so that after the next wave of impact evaluations, we’ll have enough data to speak more confidently.

That said, we do observe that programs that provide materials complementary to the training (such as textbooks or other reading materials) are significantly associated with higher learning gains, as are programs wherein participation has promotion implications. Holding the training at a university or a training center led to higher gains than training in a government administrative building or hotel. Other sizeable (but not statistically significant, potentially because of power but who knows?!) associations include lower learning gains for programs without any specific subject focus (e.g., pedagogy or technology but not focused on math or language) and higher learning gains for programs with follow-up visits in schools.

What did the implementers think? At the end of each interview, we asked the implementers what they thought the most effective program elements were. The answers given by more than one interviewee were mentoring follow-up visits, engaging teachers for their feedback and ideas (either through discussion or via text message), building on what teachers already do and linking to everyday experiences, and providing supplementary materials beyond just the training (which is consistent with the association we identified above).

Takeaways. Governments and donors spend large amounts of resources on teacher professional development. Many countries we have worked with have multiple in-service teacher training programs running at the same time, and it is likely that many are ineffective.

Most go unevaluated, but even among those that are evaluated, we observe serious weaknesses in reporting on the interventions. We will learn much more about how to improve learning if we evaluate more AND know what we are evaluating through careful reporting. Our survey instrument can help to guide reporting on a standard set of indicators.

Maybe journals don’t want lots of detail. But this is the age of the on-line appendix, and it would be easy to report the full set of implementation descriptors in such an appendix. Once we got the implementers on the phone, it took us between 60 and 90 minutes to fill in the entire instrument (60 if we stuck closely to the script; 90 if the implementer wanted to share more broadly). In the course of an impact evaluation, this is not a high cost endeavor.

We hope that even teacher training programs that are not undergoing rigorous evaluation will use this instrument, so they can learn the ways in which they are similar or dissimilar to the most effective programs. And so that – as the evidence base grows – we can get a sense of whether more programs look like the success stories or the clunkers, and redesign policy accordingly.

Postscript (aka, a relevant bit that we couldn't fit into the narrative flow of the post). One question that comes up is, Why not focus on pre-service training, so teachers are competent when they come in? Pre-service training is likely important, but one of us had a conversation with a Singaporean education expert a few years ago, in which he explained that you have to train the whole school, because otherwise any new, inexperienced teacher who comes into the school – for all her great training – is quickly assimilated into the pedagogical style of her more experienced peers. This was confirmed in a line from Banerjee et al.’s recent paper on an impact evaluation in India: “When volunteers were placed inside schools, they were used by teachers as assistants to implement traditional methods.” High-quality pre-service training is certainly valuable, but given the evidence we have, let's not discount the promise of training teachers on the job.

Join the Conversation