In my very first experiment, Suresh de Mel, Chris Woodruff, and I gave small grants of capital to microenterprises in Sri Lanka. We found that these one-time grants had lasting impacts on firm profitability for male owners. However, despite these increases in firm profits, few owners made the leap from self-employed to hiring others.

In 2008 we therefore started a new experiment with a different group of Sri Lankan microenterprises, trying to see if we could help them make this transition to becoming employers. Eight years later, I’m delighted to finally have a working paper out with the results.

The Sample and Intervention

We selected a random sample of non-agricultural urban microenterprises in three areas of Sri Lanka (Colombo, Kandy, and Galle/Matara) through a door-to-door listing survey, focusing on businesses owned by men aged 20 to 45, with two or fewer workers (only 11 percent had any paid workers). This baseline survey took place in 2008.

In April 2009 we then returned to these firms for a follow-up survey, which asked for detailed information about any employees currently working for the firm. We randomized firms into a treatment group of 250 firms, and a control group of 286 firms. The treatment group were then offered a temporary wage subsidy: we would pay a flat amount of 4,000 LKR per month (approximately half the wage of an unskilled worker) for a period of six months if they hired an additional employee working at least 30 hours per week, and a flat amount of 2,000 LKR per month for a further two months. The employee had to be someone living outside the owner’s household and could not be an immediate family member.

The idea behind this was the possibility that frictions in the labor market might be preventing firms from expanding. As a result, there could be firms for whom it would be beneficial to hire more workers, but who have not done so due to various constraints on hiring. There are several possible reasons the labor market may not clear, and why a short-term subsidy may therefore have a lasting impact:

- Search frictions and hiring costs (e.g. Mortensen and Pissarides) – if it is costly to search for and hire workers, the subsidy may encourage firms to seek out new matches, and once these have formed, this could have a long-term impact on employment.

- Uncertainty about the owner’s entrepreneurial ability (e.g. Jovanovic) – if owners don’t know how well they can manage workers until they try, there will be some firms without workers in which the owners have higher skills than they think – the subsidy might encourage them to experiment and learn they and their firm can handle having a worker

- Job-specific human capital and a lower bound on wages – workers may be less productive in their first few months while they learn the specifics of the job, with productivity increasing over time through on-the-job training (e.g. one firm in our sample raised tropical fish for export, and he said it can take a few months before you can leave a worker to care for the fish without the fish getting killed). One solution is to pay the workers low or even negative wages (as in the apprenticeship system studied by Hardy and McCasland), but this is not typical in most parts of the world. A subsidy may therefore allow the firm to cover the cost of training, so that by the end of the period the worker’s marginal product has risen to the prevailing market wage level.

We conducted 12 rounds of surveys between 2008 and 2014, enabling us to carefully measure the dynamics of adjustment to the wage subsidy, and see impacts over a four year period post-subsidy. Attrition was low, with data on employment available for 96% of firms even 3-4 years post-subsidy.

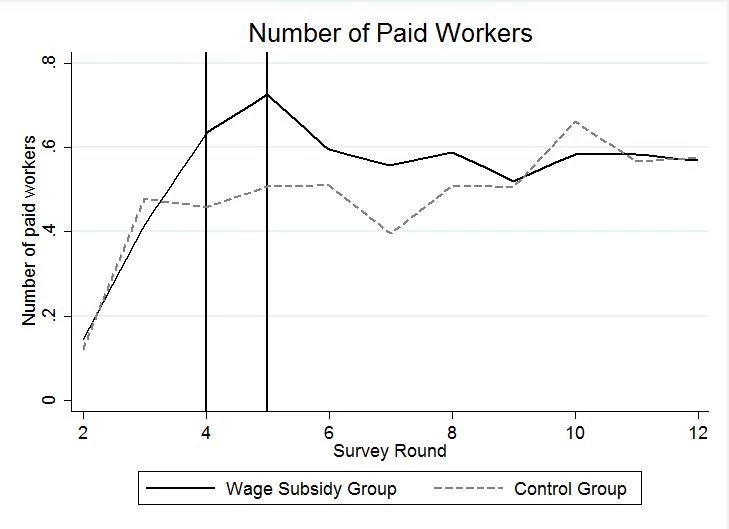

Figure 1 shows the key result. When the subsidy was offered, firms responded. 24 percent of firms used the subsidy, leading to a 20 percentage point increase in the likelihood a firm had any paid worker, and a 0.14 worker per firm increase during the subsidy period. However, once the subsidy ended, workers were fired or quit in the year immediately after the subsidy, the control group added slightly more workers as the economy grew, and after two years there is no longer any significant impact on employment.

Figure 1: Evolution of Microenterprise Employment

Note: Vertical lines show period where subsidy was in place.

We likewise find no impacts on profits or sales, and estimate that the return to an additional worker is of similar magnitude to the subsidy during the subsidy period, so that keeping unsubsidized workers is not profitable for firms. The only significant impact we find is on survival: the additional income from the subsidy appears to have enabled poorer and smaller microenterprises to remain open longer (a 5.8 percentage point increase after 4 years).

We use a variety of survey evidence, heterogeneity analysis, and complementary training and savings treatments to show that none of the three frictions identified above appear to be that important for these firms in practice. Instead the labor market facing microenterprises appears to function reasonably well, and does not appear to constrain their growth.

Finally, note the importance of timing and multiple follow-ups here: if we had just done a baseline and single follow-up immediately after the subsidy ended, we would have concluded the subsidy increases employment. Even a year later, we would have found an effect. But like has been seen with impacts on job-seekers of subsidies, the effects fade quickly here. As discussed previously on this blog, good things take time…

A 2-page impact note with some of the policy implications is also now out in the Finance & PSD Impact note series.

Join the Conversation

Very interesting results, many thanks ! How do you explain the sharp increase in the number of paid workers for both treatment and control groups in the pre-treatment period ? Do you think this specific context could have affected the incentives, and fi yes, how ? Best, Adrien

David, thanks for the very clear summary! It is very nice you managed to have so many waves of data collection. I'm wondering if firms in the experiment aren't too small to be able to generate positive impacts on jobs. These micro firms usually struggle to survive on their own. So, to hire a new employee they would have to have technologies with increasing returns, wouldn't they? Are you aware of any... other experiment with wage subsidies targeting relatively larger firms?

Read more Read lessMaybe I am missing something here. Why would firm hire if they don't notice an increase in demand for their products or don't expect any increase?