Money matters in education. Recent evidence from the United States shows that

increased education spending results in more completed years of schooling and higher subsequent wages for adults. Spending cuts during the Great Recession – also in the U.S. –

were associated with reduced student test scores and graduation rates. Indeed, the most common critique of the World Bank’s

World Development Report 2018 is that it didn’t argue strongly enough for increasing global financing for education (see

here and

here, for example). As a co-author on the WDR, I am contractually obligated (not really) to note that the report does state that, “achieving education goals, whether national or global, will certainly require more spending in the coming decades.” Okay, so we agree: More money.

But what do we need to spend more money on? Based on my conversations with teachers and school leaders in various countries, teacher salaries are often at the top of the list. Teachers argue that they need higher salaries so as not to need to spend their time racing around to side jobs in order to be able to support their families. They also argue that high pay will increase professionalism or induce higher effort through a sense of reciprocity. Several international organizations have echoed the recommendation, arguing that “ When salaries are too low, teachers often need to take on additional work…which can reduce their commitment to their regular teaching jobs and lead to absenteeism,” or “ Low pay is likely to be one of the main reasons why teachers perform poorly, have low morale and tend to be poorly qualified.” Furthermore, Ministries of Education often argue that teacher salaries need to be higher to attract the best candidates into education.

A new(ish) paper, now forthcoming at the Quarterly Journal of Economics, sheds important light on this debate: “ Double for Nothing? Experimental Evidence on an Unconditional Teacher Salary Increase in Indonesia,” by de Ree, Muralidharan, Pradhan, and Rogers. You see, a new Indonesian constitution (2000-2002) substantially increased government spending on education (to 20% of the government budget), and as a result of extensive policy decisions, the Government of Indonesia opted to dramatically increase teacher salaries.

What was the policy change?

The Government of Indonesia opted to double the base pay of civil service teachers, which translated to a two-thirds increase in net pay for teachers eligible for the reform. This moved participating teachers from the 50 th to the 90 th percentile of the salary distribution for college graduates. (The salary increase was available to a subset of teachers who were college graduates as well as civil servants.) Initially, the salary increase was intended to be conditional on an exacting assessment of teacher subject knowledge and pedagogical ability, with training for teachers who didn’t measure up. But opposition resulted in a much weaker certification: teachers had to submit a portfolio, and even a poorly evaluated portfolio resulted in a total of two weeks of training.

The salary increase was phased in over the course of ten years (2006-2015). Each year, each of Indonesia’s districts had a quota of teachers who could begin the certification process. The research team worked with the government so that uncertified teachers in 120 treatment schools had immediate access to the salary increase at the beginning of the experiment (2009), as opposed to uncertified teachers in 240 control schools, who accessed the program over the course of the next several years. Both treatment and control teachers were distributed across primary and lower secondary (“junior high”) schools.

The evaluation took place over three school years (Year 1, Year 2, and Year 3). The certification process took about a year, so treatment teachers began receiving their additional salary around the beginning of Year 2.

What happened to teachers as a result?

What about students?

There is no impact on student tests in language, mathematics, or science. There is no average impact between treatment and comparison schools. There is no impact if we restrict analysis to students of eligible teachers only. There is no impact using instrumental variables (i.e., treatment on the treated). There is no evidence of heterogeneous impacts across student wealth or student ability or proportion of teachers who are target teachers. (It feels like an adaptation of Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham: “Were there impacts for the poor? There were no impacts for the poor, there were no impacts on test scores.”

Sometimes, a lack of impact invites the rebuttal: Well, maybe you just lack the statistical power to measure the impacts. After all, as the saying goes, “the absence of evidence [of an impact] is not [necessarily] evidence of absence.” In this case, the experiment yields pretty clear evidence of absence: “The point estimates are close to zero and precisely estimated, allowing us to rule out effects as small as 0.05 standard deviations (σ) at the 95% level in treated schools. We present non-parametric plots of quantile treatment effects and find no effect on test scores in treated schools at any point in the test-score distribution.” (And there’s more in the paper!)

But what if this attracts lots of great candidates into the teaching profession?

The authors are quick to admit: “Our results do not imply that salary increases for public employees would have no positive impacts on service delivery in the long run through extensive-margin impacts.” (The "extensive-margin impacts" refer to the attraction of more capable candidates into the field.)

Here is some international evidence they cite to show that higher salaries can attract higher quality public servants:

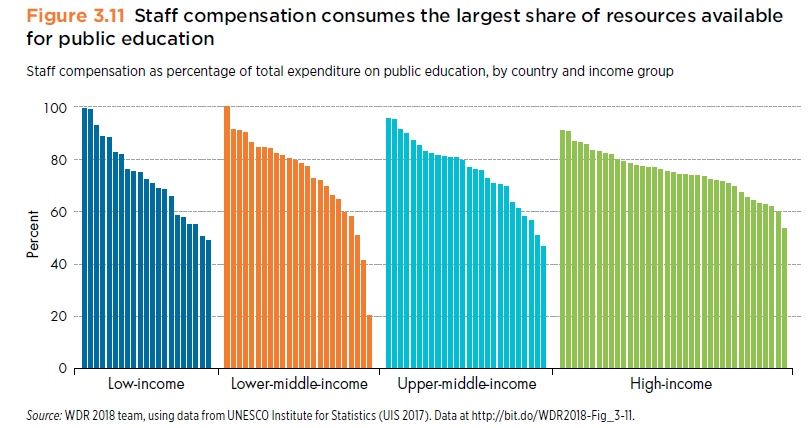

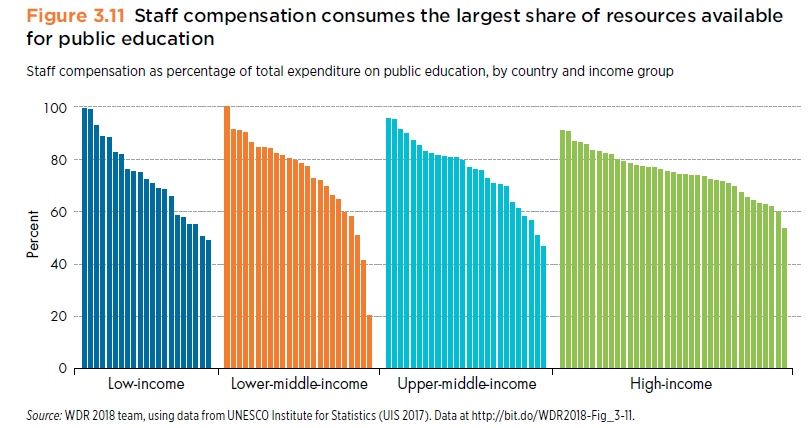

Source: World Development Report 2018

Would we observe the same results in other countries?

This is one piece of evidence from one country. Teachers in Indonesia were already paid at the 50 th percentile of the college graduate income distribution, which is higher than in some other countries (see much of Latin America, for example). So it’s of course impossible to know how well these results would travel.

Yet it’s tough to get evidence on the impact of increasing salaries that separates increased teacher salaries from other reforms, so these results should certainly make us question a knee-jerk reaction that increasing teacher salaries will raise morale and consequently effort. And the points above on cost-effectiveness should give us pause about the effectiveness of unconditional increases, as opposed to combining those with some sort of restructuring to allow performance to play a role.

Bits and pieces

But what do we need to spend more money on? Based on my conversations with teachers and school leaders in various countries, teacher salaries are often at the top of the list. Teachers argue that they need higher salaries so as not to need to spend their time racing around to side jobs in order to be able to support their families. They also argue that high pay will increase professionalism or induce higher effort through a sense of reciprocity. Several international organizations have echoed the recommendation, arguing that “ When salaries are too low, teachers often need to take on additional work…which can reduce their commitment to their regular teaching jobs and lead to absenteeism,” or “ Low pay is likely to be one of the main reasons why teachers perform poorly, have low morale and tend to be poorly qualified.” Furthermore, Ministries of Education often argue that teacher salaries need to be higher to attract the best candidates into education.

A new(ish) paper, now forthcoming at the Quarterly Journal of Economics, sheds important light on this debate: “ Double for Nothing? Experimental Evidence on an Unconditional Teacher Salary Increase in Indonesia,” by de Ree, Muralidharan, Pradhan, and Rogers. You see, a new Indonesian constitution (2000-2002) substantially increased government spending on education (to 20% of the government budget), and as a result of extensive policy decisions, the Government of Indonesia opted to dramatically increase teacher salaries.

What was the policy change?

The Government of Indonesia opted to double the base pay of civil service teachers, which translated to a two-thirds increase in net pay for teachers eligible for the reform. This moved participating teachers from the 50 th to the 90 th percentile of the salary distribution for college graduates. (The salary increase was available to a subset of teachers who were college graduates as well as civil servants.) Initially, the salary increase was intended to be conditional on an exacting assessment of teacher subject knowledge and pedagogical ability, with training for teachers who didn’t measure up. But opposition resulted in a much weaker certification: teachers had to submit a portfolio, and even a poorly evaluated portfolio resulted in a total of two weeks of training.

The salary increase was phased in over the course of ten years (2006-2015). Each year, each of Indonesia’s districts had a quota of teachers who could begin the certification process. The research team worked with the government so that uncertified teachers in 120 treatment schools had immediate access to the salary increase at the beginning of the experiment (2009), as opposed to uncertified teachers in 240 control schools, who accessed the program over the course of the next several years. Both treatment and control teachers were distributed across primary and lower secondary (“junior high”) schools.

The evaluation took place over three school years (Year 1, Year 2, and Year 3). The certification process took about a year, so treatment teachers began receiving their additional salary around the beginning of Year 2.

What happened to teachers as a result?

- Teachers earned more money! On average, teachers in treatment schools made 19% more by the end of Year 2 and 15% more by the end of Year 3. (This is less than 100% because (i) not all teachers were affected, and (ii) base pay was doubled, but other allowances all make up a significant amount of teacher salary. And the difference in pay falls in Year 2 and 3 as more control teachers become certified through the regular program.) For the eligible teachers, those numbers were 31% and 23%. So it’s still a very large salary increase.

- Teachers were happier with the money they earned! Eligible teachers in treatment schools were 28% more likely to report being satisfied with their income at the end of Year 2.

- Teachers faced less financial stress! At the end of Year 2, eligible teachers in treatment schools were 27% less likely to report financial problems.

- Fewer teachers held a second job! The pay increase also led teachers to be 19% less likely to be holding a second job.

- There is a decrease in absenteeism for eligible teachers in Year 2 (not for teachers in treatment schools on average), but it disappears by Year 3.

What about students?

There is no impact on student tests in language, mathematics, or science. There is no average impact between treatment and comparison schools. There is no impact if we restrict analysis to students of eligible teachers only. There is no impact using instrumental variables (i.e., treatment on the treated). There is no evidence of heterogeneous impacts across student wealth or student ability or proportion of teachers who are target teachers. (It feels like an adaptation of Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham: “Were there impacts for the poor? There were no impacts for the poor, there were no impacts on test scores.”

Sometimes, a lack of impact invites the rebuttal: Well, maybe you just lack the statistical power to measure the impacts. After all, as the saying goes, “the absence of evidence [of an impact] is not [necessarily] evidence of absence.” In this case, the experiment yields pretty clear evidence of absence: “The point estimates are close to zero and precisely estimated, allowing us to rule out effects as small as 0.05 standard deviations (σ) at the 95% level in treated schools. We present non-parametric plots of quantile treatment effects and find no effect on test scores in treated schools at any point in the test-score distribution.” (And there’s more in the paper!)

But what if this attracts lots of great candidates into the teaching profession?

The authors are quick to admit: “Our results do not imply that salary increases for public employees would have no positive impacts on service delivery in the long run through extensive-margin impacts.” (The "extensive-margin impacts" refer to the attraction of more capable candidates into the field.)

Here is some international evidence they cite to show that higher salaries can attract higher quality public servants:

- Higher wages attracted candidates with higher IQ and more proclivity towards public work in Mexico.

- Higher wages attracted better educated public servants in Brazil and resulted in greater legislative productivity.

- Because the total supply of teachers turns over slowly, the vast majority of those benefits would be realized far in the future, despite massive budget increases today – paying a bunch of teachers who are not becoming more effective as a result of the salary increase. So by a reasonable discount rate, this is not a cost-effective investment.

- Even if higher salaries do attract more capable individuals into teaching, “it is not obvious that this will improve social welfare, because that talent would be displaced from other sectors in the economy (unlike policies that improve the effectiveness of existing teachers).” In addition, since management quality in the public sector tends to be poorer than in the private sector, more capable individuals may be less productive in public-sector teaching than they would be in whatever sector they’re being drawn from.

- Finally, an alternative policy that links increased pay to performance in some way is likely to attract high-ability candidates – since they’ll be confident that they can receive the performance pay – but without paying low-performing teachers today.

Source: World Development Report 2018

Would we observe the same results in other countries?

This is one piece of evidence from one country. Teachers in Indonesia were already paid at the 50 th percentile of the college graduate income distribution, which is higher than in some other countries (see much of Latin America, for example). So it’s of course impossible to know how well these results would travel.

Yet it’s tough to get evidence on the impact of increasing salaries that separates increased teacher salaries from other reforms, so these results should certainly make us question a knee-jerk reaction that increasing teacher salaries will raise morale and consequently effort. And the points above on cost-effectiveness should give us pause about the effectiveness of unconditional increases, as opposed to combining those with some sort of restructuring to allow performance to play a role.

Bits and pieces

- I talked about this paper briefly in Development Impact’s “12 of our favorite development papers of the year” post from a few weeks ago.

- For a contrarian view, Jishnu Das makes the case that teacher salaries are too high rather than too low.

- Oh, and by the way, the next time someone tells you that randomized controlled trials aren’t useful for big policy questions? Send them this way.

Join the Conversation