Employment prospects for workers in rural areas are limited, but can be improved. Copyright: Shutterstock

Employment prospects for workers in rural areas are limited, but can be improved. Copyright: Shutterstock

Only about 20 percent of Colombians live in rural areas. Most Colombians prefer to live in the cities, not least because Colombian cities and urban centers generate 92 percent of all formal waged jobs in the economy. Yet few people living in urban areas have access to these jobs. Most urban workers operate in lower value-added sectors, such as commerce and construction, which have higher rates of self-employment and are rarely covered by social insurance.

In principle, a low probability of securing a better job in the city should reduce rural-to-urban migration. But there are other reasons why Colombians may be pulled into the cities despite the limited availability of stable and well-paying jobs in urban areas. Cities may offer amenities unavailable in rural areas. They may also have better schools and easier access to public services. Another key reason, postulated by Harris and Todaro, is that migration responds to urban-rural differences in expected earnings.

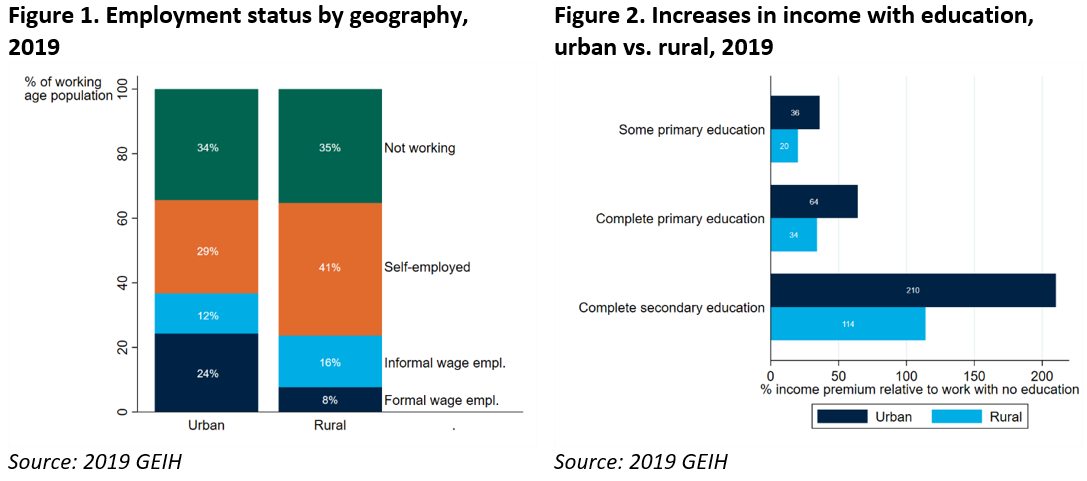

The more limited opportunities in rural areas of Colombia act as a factor pushing people into the cities. A recent World Bank Job Diagnostics Report argues that Colombia’s historic conflict not only exacerbated the flow of workers from the countryside to the city but also depressed investment into rural-urban linkages. Employment prospects for workers in rural areas are therefore particularly limited. In 2019, only 7.6 percent of the working age population in rural areas had a formal waged job, compared to 24 percent in urban areas (Figure 1). In addition, the median worker in rural areas earned only about half the hourly income of the median worker in urban areas, and earnings premiums were smaller in rural areas at all levels of education (Figure 2).

For employment outcomes to improve as countries urbanize, not only must manufacturing and high-productivity services in cities be able to absorb labor migrating from rural areas, but productivity in rural areas must also improve to curb the incentives for rural workers to move into urban areas in search of better opportunities. In Colombia, however, labor productivity in the agricultural sector is notably low for the country’s level of development and urbanization (Figure 3), and the sector is insufficiently integrated in agro-processing value chains. Food processing industries, for instance, which are intensive in agricultural inputs and can thus be an important source of formal employment in rural areas, accounted for only 0.52 percent of the rural working age population in 2019.

What can be done to ensure workers benefit from quality job opportunities in both urban and rural areas? A successful strategy requires not only actions to support labor demand and supply, but also policies and reforms beyond the labor market to address the loss of competitiveness.

Four areas of policy action deserve special attention:

- Modernizing and improving infrastructure efficiency: Colombia lags in road infrastructure quality, ranking 104 out of 142 countries. Improving the connectivity of rural areas can bolster the competitiveness of agricultural products and agro-processing activities, as well as enable further investment in agro-processing. The Colombian National Logistics Policy and current infrastructure plans are a step in the right direction.

- Promoting competition in the enabling sectors: The weak performance in agriculture and lagging integration of the sector in agro-processing value chains may be due to the high costs of key enabling activities—such as financial intermediation, transport, and real estate. Reforms that reduce entry barriers into these sectors could allow for greater competition and result in lower prices for agro-producers.

- Reducing non-tariff trade barriers and simplifying the tax regime: Simpler and more progressive taxation and export regimes can help improve the competitiveness of rural agro-processing industries, thereby creating higher quality rural employment while also incentivizing investment and exports.

- Differentiating the minimum wage across geographical areas: Colombia’s minimum wage is the same for rural and urban areas and is set at a high level—roughly 1.4 times the median rural wage between 2009 and 2019. As agro-processing employs mostly low-skilled rural labor, the high minimum wage acts as an important constraint to the development of this sector. Limiting the growth of the minimum wage relative to the productivity of workers and firms, and implementing differentiated minimum wages for urban and rural areas, would allow the agro-processing sector to employ more people.

This is the third blog of a blog series based on the World Bank Group’s report, Colombia Jobs Diagnostic: Colombia’s Structural Challenges for the Creation of More and Better Jobs. Our next blog will examine Colombia’s minimum wage and how it has contributed to hindered employment growth in the manufacturing sector and accelerated a shift in employment towards the services sectors.

Join the Conversation