We need to make sure that older workers and those already in the work force have the skills to take advantage of technological change. The ongoing debate on how advancing technology impact the demand for labor sets up a dichotomy. The future will be a utopia or a dystopia; as work reduces, society will face either unprecedented abundance or deepening inequality. But these transitions will not occur suddenly, nor will they be binary. And they will happen in very different ways depending on which firms adopt technology, and how workers might be able to respond. It is not just about youth in education; countries need to develop lifelong learning to ensure existing workers do not fall into a skills gap.

Two recent studies looking at Poland and India illuminate this unpredictability. In Poland, the changes in the task content of jobs have been substantial. But they have also created jobs. In India, the capital-augmenting technological progress has reduced labor share in gross value added, but also increased incomes of highly skilled, non-production workers. However, in both Poland and India, low skilled, production workers, and older workers have been disadvantaged as employers and economies adopt technology. Efforts to skill workers may hence need to focus on today’s workers and not only workforce entrants.

Poland: An unusual trend

Since the transition to a market economy in the 1990s, the structure of Poland’s economy changed. Employment in services grew by 2.25 million people between 1996 and 2014, equivalent to an 11.7% increase in the share of total employment. Employment in agriculture declined.

Modern services—which require higher-level skills, employ professionals, and often benefit from the use of information and communication technology (ICT)—grew the most. Similar changes occurred in manufacturing. Consequently, the intensity (the number of particular tasks performed by an average worker) of non-routine cognitive analytical and personal tasks rose between 1996 and 2014. At the same time, the intensity of routine and non-routine manual tasks declined.

However, unlike trends seen in many advanced economies, the intensity of routine cognitive tasks also rose, as Poland increased the number of medium-skilled, non-manual jobs.

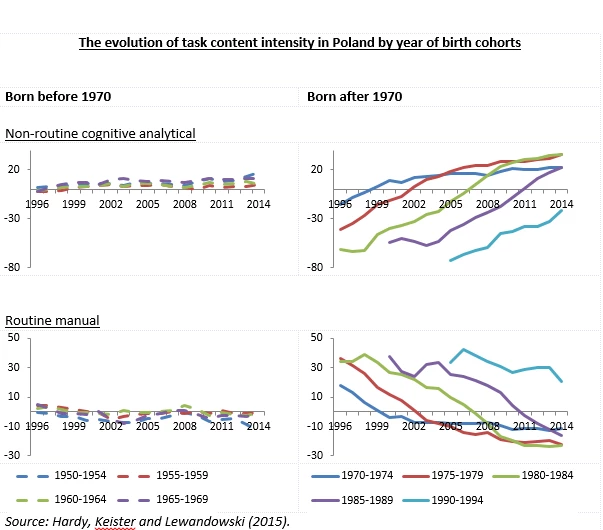

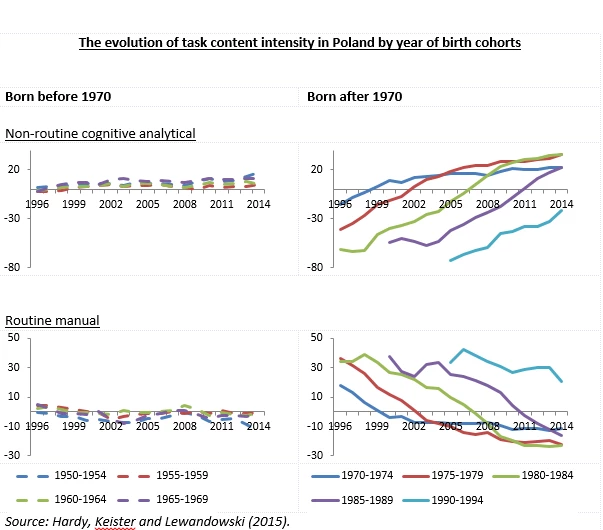

A striking difference has emerged between younger cohorts (born between 1970 and 1994), who experienced task content evolution typical for most developed countries, and older cohorts (born between 1950 and 1969), who did not. Every new cohort entering the Polish labour market since the middle 1990s reached a higher intensity of non-routine cognitive tasks than that achieved by the previous cohort at the same age.

After a dozen years of a decline in the intensity of manual tasks in Poland, in 2014 workers born between 1970 and 1989 exhibited a lower than average intensity of manual tasks than workers born between 1950 and 1969, who have barely experienced any change since the mid-1990s. The developments among the younger group accounted for the majority of the overall change in task contents recorded between 1996 and 2014.

Educational opportunities are likely responsible for these inter-generational differences. Younger cohorts benefited from increasing tertiary education enrolment since the 1970s. From the viewpoint of task content of jobs, labour demand has largely accommodated the growing inflow of better-educated entrants without deteriorating their job prospects. Younger generations may be increasingly likely to work in computerized jobs (in line with Levy and Murnane, 2013). At the same time, both the education structure and task content of jobs held by older workers have barely changed.

India’s Organized Manufacturing Sector

The liberalization of the Indian economy in the 1990s created new opportunities for its manufacturing sector. Faced with easier access to foreign technology and imported capital goods, firms in the organized manufacturing sector adopted advanced techniques of production. This led to increased automation and a rise in the capital intensity of production.

This has raised much concern about the ability of the manufacturing sector to create jobs for India’s rapidly rising, largely low skilled and unskilled workforce. However, what has attracted less attention in the literature is the impact of capital augmenting technological progress on the distribution of income and wage inequality. Using enterprise level data from the India’s Annual Survey of Industries, we see that with growing capital intensity of production, the role of labour vis-à-vis capital has declined.

The share of total emoluments paid to labour fell from 34.7% to 22.4% of gross value added (GVA) between 2000-2001 and 2011-12. At the same time, the share of wages to workers in GVA declined steeply from 26.9% to 18.5%. Commensurately, the share of profits in GVA rose from 19.9% to 46.1% of GVA over the same period. This declining share of GVA going to workers rather than capital, raises the issue of equity in the distribution of income.

Importantly, even within the working class, inequalities have increased. The share of skilled labour such as non-production supervisory and managerial staff in the wage pie rose from 26.1% to 35.8%. At the same time that of unskilled production workers fell from 57.6% to 48.8% of the total wage bill. The rising disparity in the wages of skilled and unskilled workers is also reflected in the fact that the ratio of the average wages paid to them increased from 3.6 to 5.7 over the last decade.

These results underline the existence of capital-skill complementarity: firms with higher capital intensity employed a higher share of skilled workers and the wage differential between skilled and unskilled workers was higher in these firms. The fact that technological change has not been accompanied by a large increase in the supply of skilled workers has exacerbated wage disparity.

The Government of India’s ambitious Skill India program, with a target to skill 400 million workers over the next five year attempts to address this gap. However, assembly line methods of skill development which produce large numbers of electricians, machine operators, plumbers and other such narrowly skilled and certified persons will not address India’s skills challenge.

Takeaways

Technological advancement will create new types of jobs. In Poland, many younger workers benefited from education that allowed them to participate in an increasingly sophisticated, digital economy. But older workers may be left behind by technological progress and the emergence of new types of jobs. In India, workers that had the skills to use and manage more technologically-advanced processes and firms benefited. Poorly skilled workers lacked the skills to catch up with new modes of production.

Public policy will need to consider how to improve the skills or older and less-skilled workers to adapt to technological change. This is especially the case for countries with undeveloped systems of life-long learning. This means going beyond the important task of preparing young people for the future of work, but also ensuring that today’s (and tomorrow’s) workers are able to learn and update their skills, as enterprises adopt technology and seek higher-skilled workers.

Two recent studies looking at Poland and India illuminate this unpredictability. In Poland, the changes in the task content of jobs have been substantial. But they have also created jobs. In India, the capital-augmenting technological progress has reduced labor share in gross value added, but also increased incomes of highly skilled, non-production workers. However, in both Poland and India, low skilled, production workers, and older workers have been disadvantaged as employers and economies adopt technology. Efforts to skill workers may hence need to focus on today’s workers and not only workforce entrants.

Poland: An unusual trend

Since the transition to a market economy in the 1990s, the structure of Poland’s economy changed. Employment in services grew by 2.25 million people between 1996 and 2014, equivalent to an 11.7% increase in the share of total employment. Employment in agriculture declined.

Modern services—which require higher-level skills, employ professionals, and often benefit from the use of information and communication technology (ICT)—grew the most. Similar changes occurred in manufacturing. Consequently, the intensity (the number of particular tasks performed by an average worker) of non-routine cognitive analytical and personal tasks rose between 1996 and 2014. At the same time, the intensity of routine and non-routine manual tasks declined.

However, unlike trends seen in many advanced economies, the intensity of routine cognitive tasks also rose, as Poland increased the number of medium-skilled, non-manual jobs.

A striking difference has emerged between younger cohorts (born between 1970 and 1994), who experienced task content evolution typical for most developed countries, and older cohorts (born between 1950 and 1969), who did not. Every new cohort entering the Polish labour market since the middle 1990s reached a higher intensity of non-routine cognitive tasks than that achieved by the previous cohort at the same age.

After a dozen years of a decline in the intensity of manual tasks in Poland, in 2014 workers born between 1970 and 1989 exhibited a lower than average intensity of manual tasks than workers born between 1950 and 1969, who have barely experienced any change since the mid-1990s. The developments among the younger group accounted for the majority of the overall change in task contents recorded between 1996 and 2014.

Educational opportunities are likely responsible for these inter-generational differences. Younger cohorts benefited from increasing tertiary education enrolment since the 1970s. From the viewpoint of task content of jobs, labour demand has largely accommodated the growing inflow of better-educated entrants without deteriorating their job prospects. Younger generations may be increasingly likely to work in computerized jobs (in line with Levy and Murnane, 2013). At the same time, both the education structure and task content of jobs held by older workers have barely changed.

India’s Organized Manufacturing Sector

The liberalization of the Indian economy in the 1990s created new opportunities for its manufacturing sector. Faced with easier access to foreign technology and imported capital goods, firms in the organized manufacturing sector adopted advanced techniques of production. This led to increased automation and a rise in the capital intensity of production.

This has raised much concern about the ability of the manufacturing sector to create jobs for India’s rapidly rising, largely low skilled and unskilled workforce. However, what has attracted less attention in the literature is the impact of capital augmenting technological progress on the distribution of income and wage inequality. Using enterprise level data from the India’s Annual Survey of Industries, we see that with growing capital intensity of production, the role of labour vis-à-vis capital has declined.

The share of total emoluments paid to labour fell from 34.7% to 22.4% of gross value added (GVA) between 2000-2001 and 2011-12. At the same time, the share of wages to workers in GVA declined steeply from 26.9% to 18.5%. Commensurately, the share of profits in GVA rose from 19.9% to 46.1% of GVA over the same period. This declining share of GVA going to workers rather than capital, raises the issue of equity in the distribution of income.

Importantly, even within the working class, inequalities have increased. The share of skilled labour such as non-production supervisory and managerial staff in the wage pie rose from 26.1% to 35.8%. At the same time that of unskilled production workers fell from 57.6% to 48.8% of the total wage bill. The rising disparity in the wages of skilled and unskilled workers is also reflected in the fact that the ratio of the average wages paid to them increased from 3.6 to 5.7 over the last decade.

These results underline the existence of capital-skill complementarity: firms with higher capital intensity employed a higher share of skilled workers and the wage differential between skilled and unskilled workers was higher in these firms. The fact that technological change has not been accompanied by a large increase in the supply of skilled workers has exacerbated wage disparity.

The Government of India’s ambitious Skill India program, with a target to skill 400 million workers over the next five year attempts to address this gap. However, assembly line methods of skill development which produce large numbers of electricians, machine operators, plumbers and other such narrowly skilled and certified persons will not address India’s skills challenge.

Takeaways

Technological advancement will create new types of jobs. In Poland, many younger workers benefited from education that allowed them to participate in an increasingly sophisticated, digital economy. But older workers may be left behind by technological progress and the emergence of new types of jobs. In India, workers that had the skills to use and manage more technologically-advanced processes and firms benefited. Poorly skilled workers lacked the skills to catch up with new modes of production.

Public policy will need to consider how to improve the skills or older and less-skilled workers to adapt to technological change. This is especially the case for countries with undeveloped systems of life-long learning. This means going beyond the important task of preparing young people for the future of work, but also ensuring that today’s (and tomorrow’s) workers are able to learn and update their skills, as enterprises adopt technology and seek higher-skilled workers.

Join the Conversation