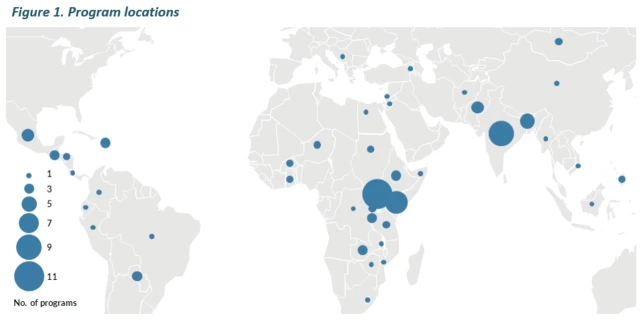

Targeted household-level economic inclusion programs are on the rise: nearly 100 programs across 43 countries have reached an estimated 14 million people to date, according to the Partnership for Economic Inclusion’s (PEI) 2018 State of the Sector report. These programs provide a “big push” to help the extreme poor and other vulnerable people move into sustainable livelihoods, and can play an important part in poverty reduction and the new “social contract”, as noted in a recent blog.

The 2018 State of the Sector report presents findings from a survey of nearly 100 programs that self-reported data in fall 2017 and includes information on the number and size of programs across low- and middle-income countries, as well as innovations in program design and delivery and research underway. Many of these projects are funded or implemented by the World Bank, including the Adaptive Social Protection Program in Niger, the livelihood component of the Ethiopia’s Rural Productive Safety Net Project, and the Girls Education and Women’s Empowerment and Livelihood (GEWEL) Project in Zambia. Four key trends emerged from the data:

- The momentum is strong, especially with governments. Government take-up of deeply targeted economic inclusion programs has dramatically increased since 2016, with 34 governments implementing and/or funding programs (a two-fold increase since 2016). In most cases, government social protection infrastructure—such as cash transfers and other safety nets—forms the backbone on which targeted economic inclusion programs are built. Some programs, such as Ghana’s Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) program and Sudan’s Social Safety Net Program also build on government labor market programs to combine skills training with productive capital transfers.

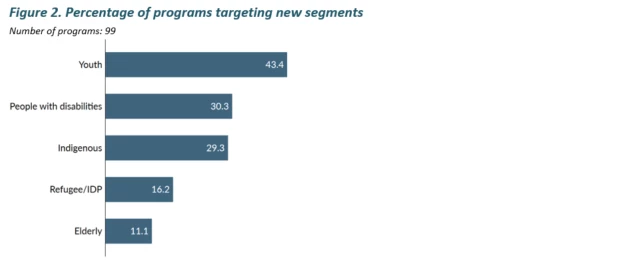

Note: The size of the circle indicates the number of programs in a given country - Reaching new populations. While most programs focus on increasing food security and income-earning opportunities for rural women, new population segments are also being reached (see figure below). Over 40% of programs in the survey target youth and seek to foster opportunities for unemployed and vulnerable young people. Nearly a third of programs work with people with disabilities to increase their skills and sense of empowerment, such as Paraguay’s Integrated Graduation Approach for Indigenous Communities. Sixteen percent of programs, many of them led by the UN’s refugee agency, are also targeting refugee or internally displaced people to increase self-reliance by adding livelihood development and coaching onto existing humanitarian interventions. Programs are also broadening their sensitivity to gender issues with design tweaks such as adding training modules on women’s rights and leadership, sexual and reproductive rights, avoiding early marriage, political empowerment, and girls’ education.

- Expanding into new contexts. Programs, such as Paraguay’s Urban Graduation Strategy in Programa Abrazo, are expanding to include urban and peri-urban areas. In doing so, they are increasingly facilitating access to wage employment, rather than exclusively focusing on self-employment, seeking to make the most of more vibrant urban job market opportunities. The survey also shows that 75% of programs are expanding into humanitarian and post-humanitarian contexts, operating in fragile or conflict-affected countries (as defined by the OECD), which requires further innovation to identify effective program adaptations to meet the needs of participants in these contexts.

- Innovating and adapting. Economic inclusion packages are also evolving in an effort to increase the cost-effectiveness of programs. A number of organizations, such as BRAC, are providing the income-earning capital in the form of loans or soft loans instead of grants. Delivering some program components digitally is also a trend: 43% of programs reported providing at least one component via phones, tablets, or other technology-enabled channels, including for consumption assistance (44% of programs delivering this component did so digitally), seed capital (34%), and access to savings (18%)

Moving forward, PEI will work across teams at the World Bank and with the wider Economic Inclusion Community of Practice to increase the scope of the 2019 State of the Sector, including through a more systematic tracking of economic inclusion programs within broader social protection and labor systems.

Follow the World Bank Jobs Group on Twitter @wbg_jobs.

Join the Conversation