Piotr Lewandowski is President of the Institute for Structural Research in Warsaw.

The political and economic transition of post-communist Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries brought major improvements in GDP per capita, productivity, incomes, and living standards. But certain worrying phenomena have emerged in the labor markets, reminiscent of earlier developments in Western and Southern European countries. One of these is a rise in temporary employment, which has created a “dual labor market” – that is, a segmented market with workers in one segment more privileged than those in the other. For Spain, Portugal, and Italy, this problem arose in the 1980s, whereas for the CEE economies – especially Poland – the onset was in the 2000s. Fortunately, a variety of possible solutions exist. But so far, the Polish government has done little to improve the situation.

A Growing Dual-Labor Market

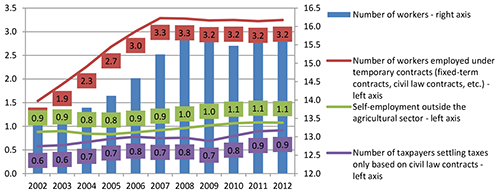

Just how bad is the problem? In 1998, only 4.7% of Polish workers had contracts that didn’t ensure stable employment. But since then, the share has risen to 26.9% – the largest increase in Europe and one that is comparable only to that of Portugal and Spain. In 2012 there were 15.6 million Polish workers, out of which 9 million had open-ended (“regular”) contracts, 3.2 million had temporary contracts, and 1.1 million individuals were self-employed outside the agricultural sector (see figure 1). The remaining 2.3 million workers were farmers (self-employed).

(Number of persons working under various legal forms in Poland, 2002–2012, in millions)

Note: Taxpayers settling taxes only based on civil law contracts are a subgroup of temporary workers. Sources: Eurostat, Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS), and Polish Ministry of Finance.

However, there are two crucial differences between the Polish case and that of Spain and Portugal, as pointed out in my recent paper (with Piotr Arak and Piotr Żakowiecki). First, unlike Spain, where the proliferation of temporary contracts followed the 1984 labor code reform (which deregulated temporary contracts while maintaining strict protection of permanent contracts), there was no such reform in Poland. Indeed, in Poland, protection of open-ended contracts and severance pay requirements has remained moderately strict, and there hasn’t been any significant deregulation of rules pertaining to temporary contracts. Second, besides fixed-term employment contracts (which are based on the Polish labor code but expire on a specific date), another class of contracts has been used to formalize work – those based on the civil law. Within that group, there are two types: (i) contract of mandate (exchange of services); and (ii) contract for results (exchange of deliverables).

In the early stage of Poland’s economic transition, when setting up a business was complex and time consuming, these contracts were used mainly by freelancers and exchanges between individuals. But recently they have been commonly used by firms to contract labor on precarious terms. The Ministry of Finance estimates that in 2012, 916,000 people worked solely under civil law contracts, almost double the 2002 level of 580,000. And the Polish Statistical Office believes that the 2012 level may have even reached 1.35 million, based on a survey of firms employing at least 9 workers.

Why is this trend such a problem? The reality is that civil contract workers – compared with open-ended, and even fixed-term employment contract workers – experience lower pay, less job stability, less on-the-job training, a higher risk of poverty, and poorer access to credit and mortgage markets. This occurs because the labor code provisions (like justified reason for dismissal, termination notification period, or severance payment) don’t apply to these contracts; neither do the requirements concerning occupational health and safety and appropriate working conditions and the minimum wage.

Moreover, social security contributions are much lower for civil law contracts. Social Insurance Institution data shows that workers with these contracts pay on average 25% of contributions paid by similar workers with employment contracts. As a result, the difference in the tax wedge placed on employment and civil law contracts is substantial (see figure 2), especially for low-paid workers. Thus using civil law contracts in lieu of employment contracts is attractive for both workers and employers in Poland, as they offer higher current income to a worker and lower total costs as well as less red-tape to an employer. The readiness to accept them or willingness to achieve a higher income at the expense of lower stability and lack of social security contribution payment is particularly high among low-paid workers.

(Contribution and tax wedge depending on gross remuneration (in zlotys) and type of contract, 2013)

Note: The tax wedge is the difference between the labor cost incurred by the employer (income tax and social security contributions) and the net remuneration received by the worker. Source: Authors’ calculations.

Skirting the Issue

The emergence of Poland’s dual labor market provides an important lesson for other countries – namely, substantial changes in the labor market can result not only from a single policy mistake (as occurred in Spain in the 1980s) but also from the interaction of several regulations. In Poland’s case, the culprit is a legal system that allows employers to use contracts that don’t have to adhere to some labor code provisions, minimum wage regulations, and the social security system. So far, the government has failed to address the issue properly. It has only passed a law to increase the social security contributions on civil law contracts from 2016. Left unaddressed is the precariousness of these contracts, and the incentive to relocate low-paid jobs to the shadow economy will increase.

(The next Jobs and Development blog will explore the author’s proposal for overcoming the deadlock on this issue. See also an interview with Tito Boeri on “Replacing Europe’s Dual Labor Markets with a Single Contract” and videos from the IBS October 8-9 conference in Warsaw on “Dual labour markets, minimum wage and inequalities.”)

Join the Conversation