Jesus Felipe is an Advisor in the economics and research department at the Asian Development Bank.

Aashish Mehta is an Associate Professor of Global and International studies at UC-Santa Barbara.

Changyong Rhee is a Director in the Asia and Pacific Department at the International Monetary Fund.

In a recently released working paper, we have analyzed data on manufacturing employment and output levels from developing and developed countries. We show that historical manufacturing employment levels are much better predictors of subsequent prosperity than historical manufacturing output levels. Unfortunately, we also find that late industrializers are likely to face significant difficulty achieving high manufacturing employment shares, even if they are successful in spurring high levels of manufacturing activity. Therefore, while manufacturing jobs are key, it will be difficult for today’s late industrializers to replicate past success with development through manufacturing job creation.

In a recently released working paper, we have analyzed data on manufacturing employment and output levels from developing and developed countries. We show that historical manufacturing employment levels are much better predictors of subsequent prosperity than historical manufacturing output levels. Unfortunately, we also find that late industrializers are likely to face significant difficulty achieving high manufacturing employment shares, even if they are successful in spurring high levels of manufacturing activity. Therefore, while manufacturing jobs are key, it will be difficult for today’s late industrializers to replicate past success with development through manufacturing job creation.

A long tradition in development economics treats manufacturing as special. Some of the development benefits the sector provides rely on large and growing numbers of manufacturing jobs, not just rising levels of manufacturing output. Labor productivity in manufacturing converges rapidly towards international norms. This gives aggregate productivity a bigger boost; the larger the share of the workforce that is in manufacturing, the greater the boost. The more rapid the manufacturing employment growth, the faster workers move out of low-productivity, low-wage agriculture and traditional services.

Unfortunately, cross-country analysis of the connections between manufacturing employment and levels of development has been restricted to OECD countries. This matters because many developing country governments have large programs to stimulate manufacturing activity, on the understanding that jobs and higher incomes will follow. Ambitious job targets are announced - such as 100 million new manufacturing jobs by 2022 in India. These are typically justified with reference to the experiences of earlier industrializers, like Korea and Taiwan. Public budgets, land and labor regulations, and even education policy are being modified to pursue these manufacturing jobs. We can see why developing countries want these manufacturing jobs: our data show that a country’s peak manufacturing employment share between 1970 and 2010 rather than is its peak manufacturing output share, is a much better predictor of its average per capita GDP in 2005-2010. Controlling for peak manufacturing employment shares and the date that manufacturing activity peaked, peak output shares are insignificant predictors of subsequent prosperity. This suggests that manufacturing output matters for prosperity only insofar as it comes with jobs. Moreover, we show that every country that is rich today, by any reasonable standard, had more than an 18-20% manufacturing employment share sometime since 1970.

It is important to note that industrial activity typically grows with income in poorer countries, peaks, and then falls with income and wages in richer (deindustrializing) countries. There are two reasons we think that manufacturing employment-led development is becoming more challenging.

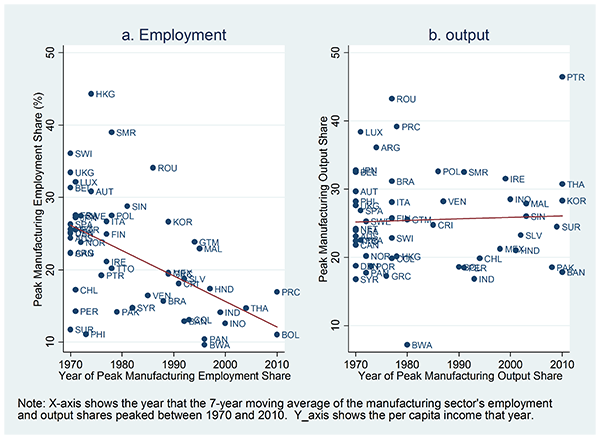

- Labor productivity has risen faster in manufacturing than in the wider economy. Higher levels of manufacturing output are now compatible with lower levels of manufacturing employment. Figure 1 confirms this, showing that peak manufacturing employment shares have fallen over time. Peak output shares have not.

Figure 1: Manufacturing Employment Shares Have Declined, Output Shares Have Not

- Manufacturing activity is now more apt to leave for other countries as labor costs rise. Therefore deindustrialization kicks in at lower income levels. Moreover, this premature deindustrialization is more apparent in employment than in output data. Output can be sustained in the face of rising labor costs by replacing workers with machinery. (Arvind Subramaniam and Amrit Amirapu show similar trends in industrial (manufacturing plus mining, utilities and construction) employment using repeated cross-sections of countries.)

Countries still industrialize and then deindustrialize as they become richer. However, industrial employment shares for today’s late industrializers such as China, India and Bangladesh are all below 16%, and on today’s trends seem unlikely to rise much further. Moreover, the per capita income levels at which deindustrialization kicks in have fallen from $34,000 in 1970 to around $9,000 in 2010.

These results urge a balanced approach to industrialization. They confirm that industrialization matters – when it brings jobs; but they also confirm that this is less and less likely to happen. Governments must not neglect manufacturing. Nor can they rely as heavily on it as they once did.

Join the Conversation