Young woman in Guatemala.

Young woman in Guatemala.

Imagine the despair one needs to be facing to decide to walk 4,000 km along a dangerous migration corridor, endangering one's life and the lives of one's children. Confronted with persistent poverty and lack of hope, many Central American individuals and families turn to this risky option, hoping it will open doors to a better life in another country.

Today, Guatemala is at the epicenter of this migration crisis. The number of migrants from Guatemala rose from 9,000 people annually, during the 2000s, to three times this figure in 2018. This surge is driven predominantly by outmigration from rural areas. Migrants are also leaving the country at a younger age. The average age at the time of migration fell from 28 in the 2000s to 25 in the 2010s. During the early 2000, children and youth below the age of 18 represented only 15% of the migrants versus 30% in 2018.

What explains this surge?

Figure 1: Guatemalan emigrants, urban versus rural areas, 2004-2018

Figure 2: Children & Youth as % total emigrants, 2004-2018

A World Bank Jobs Diagnostic analyzes Guatemala’s labor market between 2004 and 2018 and casts light on what has been pushing so many young people to leave their country.

- Widespread poverty has been exacerbated by a steep deterioration of the job market opportunities for rural youth. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Guatemala had high levels of informality and few jobs that paid enough to make a living. The situation is dire in rural areas, where most people depend on agriculture and cannot escape poverty. The lack of quality jobs contrasts with the rising number of more educated graduates entering the labor market every year. This leaves many school graduates with little hope of finding a decent job. In 2018, a young adult completing secondary education in a rural area expected to earn only 64% of what he or she would have earned back in 2004!

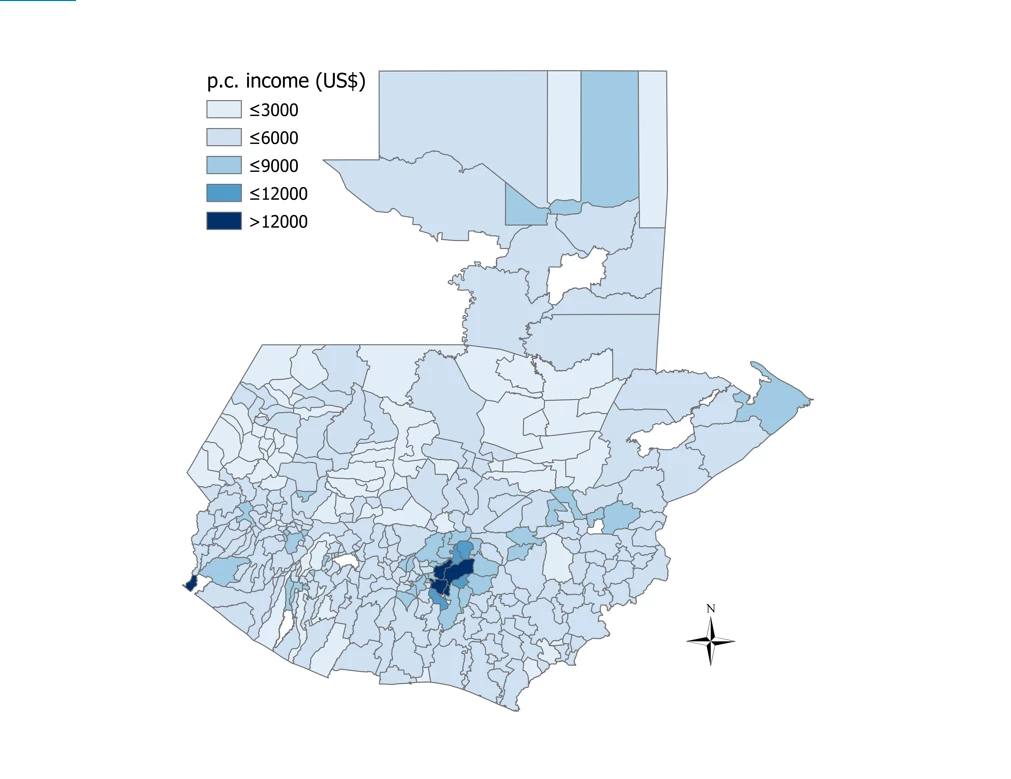

- Youth face significant constraints migrating internally to richer areas; hence, they often choose to migrate internationally. Average incomes in Guatemala are highly unequal. They range from US$1,118 per year in Santa Bárbara, Huehuetenango to almost US$15,000 in Petapa, near Guatemala City (figure 3). Despite these disparities, internal migrants from the most deprived parts of the country find it much harder to secure good jobs than those that move from the richer parts of the country, possibly on account of higher language barriers and more limited support networks. So, they often try their luck abroad. That is one of the reasons why municipalities that exhibit lower rates of internal outmigration have higher rates of international outmigration.

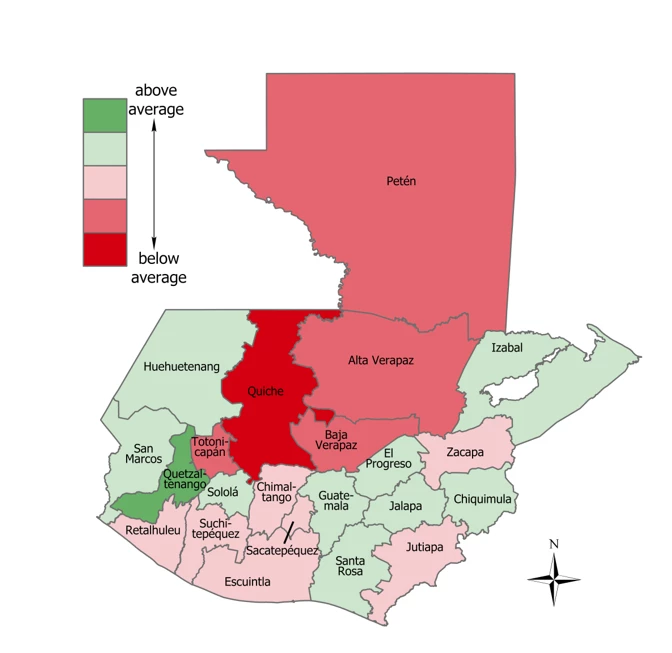

- Limited access to education and low education quality among rural youth hinder access to “good” jobs in urban areas. Despite progress in school enrollment over the last decade, Guatemala has a large rural-urban gap in learning outcomes, equivalent to a difference of two years of schooling. Schooling quality is particularly poor in the north and rural parts of the country (figure 4). Good jobs may prove elusive even when offspring progress to higher levels of education than their parents, making it harder for families to break out of the intergenerational cycles of poverty. This often prompts entire families to migrate.

The increasing exposure to extreme weather events, coupled with the long-term effects of the pandemic, add further pressure to migratory outflows from the poorest regions.

The heavy reliance on agriculture makes rural livelihoods especially vulnerable to natural disasters, like hurricanes and flooding, which are expected to intensify due to climate change. Limited access to health, water or sanitation services in these areas also reduces the response capacity in the aftermath of disasters. This adds to people’s sense of despair at home.

Moreover, the long-term effects of the pandemic will be especially severe on youth, as school closures are likely to reduce learning outcomes for many years to come. With more limited internet penetration that hinder schooling-from-home arrangements during the pandemic, youth in rural areas will be particularly affected.

But what could be done?

Policy reforms to promote more balanced economic opportunities and outcomes across the regions, are critical to facilitate more inclusive development. A consistent focus of public policy in this direction is needed building on three pillars.

- Strengthened education quality, particularly in the more deprived departments to the north of the country. Guatemala’s ongoing demographic transition offers a unique opportunity to address major spatial inequalities. With fewer births, pressures on the schooling system and social services will start to ease, particularly in the richer region. This can enable the reallocation of public resources to communities most in need.

- A big push to raise labor productivity, remove barriers to formalization of jobs, and attract increased investment to the poorer regions of the country. Guatemala’s economy is heavily dependent on the activity of its formal sector firms. The presence of larger and more productive firms is low outside Guatemala City and its surrounding regions. Revising the enabling environment and incentivizing the establishment of creation and growth of more productive formal firms in more remote places would help to generate more equal geographical opportunities. Minimum wage legislation, for instance, could be reformed to better reflect the large differences in labor productivity within the country. And improvements in port and road infrastructure would ensure better connectivity of national and international markets and spur trade.

- A greater tax effort is needed to finance an expansion and enhancement of public services and public infrastructure throughout the country. The current tax-to-GDP ratio of around 10-11% is extremely low and proves insufficient to address the major physical and human capital investment needs that could place the country in a more dynamic and inclusive growth path.

Figure 3: Per capita income by municipality, 2017 (in current US$)

Figure 4: Regional Education Quality Gap

Join the Conversation