In the post-COVID recovery phase, a well-thought-out reform program of labor regulations and social protection financing will be needed in MENA. Photo: Dominic Chavez/World Bank

In the post-COVID recovery phase, a well-thought-out reform program of labor regulations and social protection financing will be needed in MENA. Photo: Dominic Chavez/World Bank

Labor market regulations are important determinants of productivity and labor market outcomes. They can protect workers’ rights, enhance job security, and improve working conditions. However, overly- restrictive regulations can also increase business costs, becoming barriers to creating formal employment and thus, can undermine productivity growth in the economy. In some respects, MENA’s labor regulations remain relatively restrictive, which may be hindering the movement of workers into better jobs, while in others, they may also be providing insufficient protection to some workers.

Over the past decade, MENA’s reforms in labor market regulations have been limited. As Covid recedes and the region turns to address the persistent labor market challenges that predated the pandemic, it is a good time to rethink the design of the labor regulatory system and the related challenges of modernizing its social protection systems.

The considerable global literature on labor regulations has relatively little coverage of MENA. Our new working paper analyzes and compares labor regulations in 19 MENA economies and benchmarks them against international practices in areas that affect formal sector employment creation and workers’ transitions: regulations concerning hiring, working hours, minimum wages, redundancy rules severance pay, unemployment insurance, labor taxes and social security contributions, and the legal frameworks affecting women’s work. This blog summarizes some of our key findings.

Minimum wage policies need to be revisited

Many MENA countries have not recently revised their minimum wage levels. For example, Lebanon's minimum wage has been unchanged since 2012. They should consider more frequent adjustments, to consider changes in local economic and social conditions. At the same time, a quarter of countries in MENA do not have a national minimum wage for private-sector workers. And when they exist, minimum wages normally exclude some categories of workers such as domestic workers or migrants. Only in Kuwait and Qatar do minimum wages apply to domestic workers. Countries with no minimum wages should consider establishing them at levels aligned to productivity in their formal sector, so as to not only ensure an adequate income for workers but also to avoid discouraging the creation of more formal sector jobs.

Many countries rely on severance pay but lack unemployment benefits

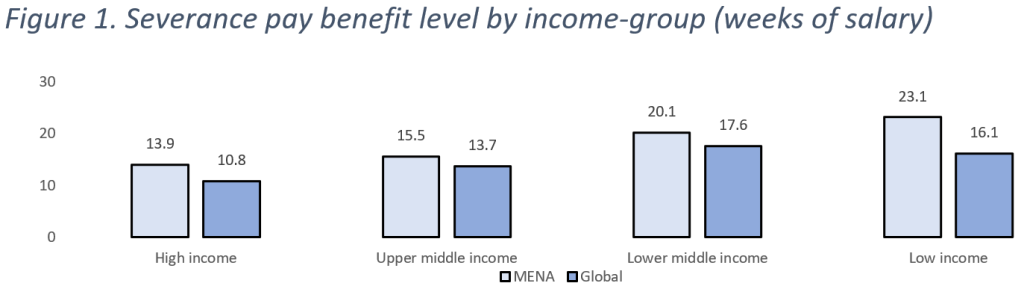

The region provides for relatively high severance payments (see Figure 1). At the same time, only nine countries have unemployment insurance schemes. But generous severance pay and overly protective dismissal rules are a poor substitute for well-functioning unemployment insurance since they add to employers’ labor costs while also incentivizing inflexibility in the formal labor market. Governments should consider introducing or strengthening unemployment insurance schemes to replace them, because they are a better option to protect workers in transition between jobs.

Note: MENA = Middle East and North Africa. Average weeks are calculated only for countries with severance pay requirements.

Labor taxes tend to be high in some countries

In Algeria, Iran, Egypt, Tunisia, and Lebanon, more than a quarter of corporate profits are spent on labor taxes and contributions. In Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, on the other hand, the average labor tax is relatively low, but even there, the ratio of labor taxes to total taxes tends to be high. Labor taxes and social security contributions create a “tax wedge” which increases the employer’s labor costs relative to workers’ net wages, lowering labor demand in the formal sector and sometimes also incentivizing employers to hire workers informally. The region should consider options to lower the tax wedge by setting social security contributions at modest levels and by shifting away from the use of labor taxes towards other revenue sources, such as general income, consumption, and property taxes.

Women are barred from equal opportunities

Our study also underlines that women in MENA face multiple layers of legal restriction and inequality in the workplace. These wide-ranging barriers include restrictions on employment in some industries and on working hours, requirements for work permission from husbands, limited maternity leave, and unequal retirement ages.

For example, none of the GCC countries has a law establishing paid leave for private-sector working mothers that meets the 14-week international standard. Moreover, of the 19 countries in the world where women still need permission from their husbands to get jobs, nine are in the MENA region (the other 10 are in Sub-Saharan Africa).

Gender-discriminatory laws and regulations restrict women's participation in the labor market and result in wage gaps between men and women. MENA’s governments should consider legislating to enhance women’s working rights whilst also improving their work environments by supporting maternity and paternity leave, childcare, and flexible working hours.

What policymakers should know

A key issue is that although, de jure, MENA’s labor regulations are highly protective (at least, of male formal sector workers), evasion can render them, de facto, ineffective in really protecting workers. This is due both to non-compliance within the formal sector; and to the increase of informal employment that results from employers evading the costs of the formal sector “tax wedge”. As a result, most workers in the MENA region remain unprotected against employment shocks.

To reduce non-compliance in the formal sector, the region should improve labor inspectorates’ capacity to monitor workers’ rights and enforce regulations. Enhancing awareness of legal obligations for both workers and employers also helps the enforcement of legal rights. But to reduce the unnecessarily high rate of informality, the region should also modernize the design of labor regulations and re-think the distribution of protective functions between labor laws and social protection systems. Where the latter require subsidies, they should be transparent and funded from general taxation, rather than being funded by a levy on the hiring of formal sector labor.

As MENA enters the recovery phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments should move to replace temporary crisis responses by a well-thought- out reform program of labor regulations and social protection financing arrangements. When calibrating labor regulations, policymakers should aim to avoid extremes. When combined with unemployment insurance, active labor market programs and tax-funded universal social protection arrangements, more balanced labor regulations can help to make labor markets more dynamic, facilitating productivity and earnings growth, while providing employment security and protection to workers.

Join the Conversation