Producción de cacao, Honduras

Producción de cacao, Honduras

New findings show that, like their counterparts in many neighboring countries, Honduran women are sorely underrepresented in the job market. Because of this, the country’s economy is losing about 22 percent of potential per capita income – even more than the 17 percent loss for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Why is this important? First, Honduras has a huge potential workforce: two out of every three people in Honduras are of working age (15-64 years old), but of those two, only one works. That means only one out of three people are benefiting from labor income and contributing to the economy. Second, for every 10 working-age men who actively participate in the labor market, only 5.5 women do. Taken together, these numbers mean that Honduras is missing out on growth by not employing more of its women.

So, why do young Honduran men find jobs while young women don’t?

Holding out for better jobs

The recent World Bank’s Jobs Diagnostic for Honduras pinpoints the absence of better-quality, safe, and secure jobs as a key reason for women’s limited participation. In other words, women are holding out for better jobs. Different data shows this:

- Lack of education does not seem to be the cause for the gender gap in workforce participation. By 2016, 12 percent of young women (15-24 years old) had attained some tertiary education while only 10.8 percent of young men had. Also, a larger share of boys had not completed primary schooling (14.1 percent vs. 10.9 percent of girls).

- Young women who work earn 12 percent more than young men who work. This supports the hypothesis that women may prefer holding out for better jobs, while young men tend to take what is available.

- Young women who have completed primary but not secondary school may suffer the most from insufficient jobs, and they represent 65 percent of all young women. This group is far less likely to be active in the labor market than both men with similar schooling and women with a higher education.

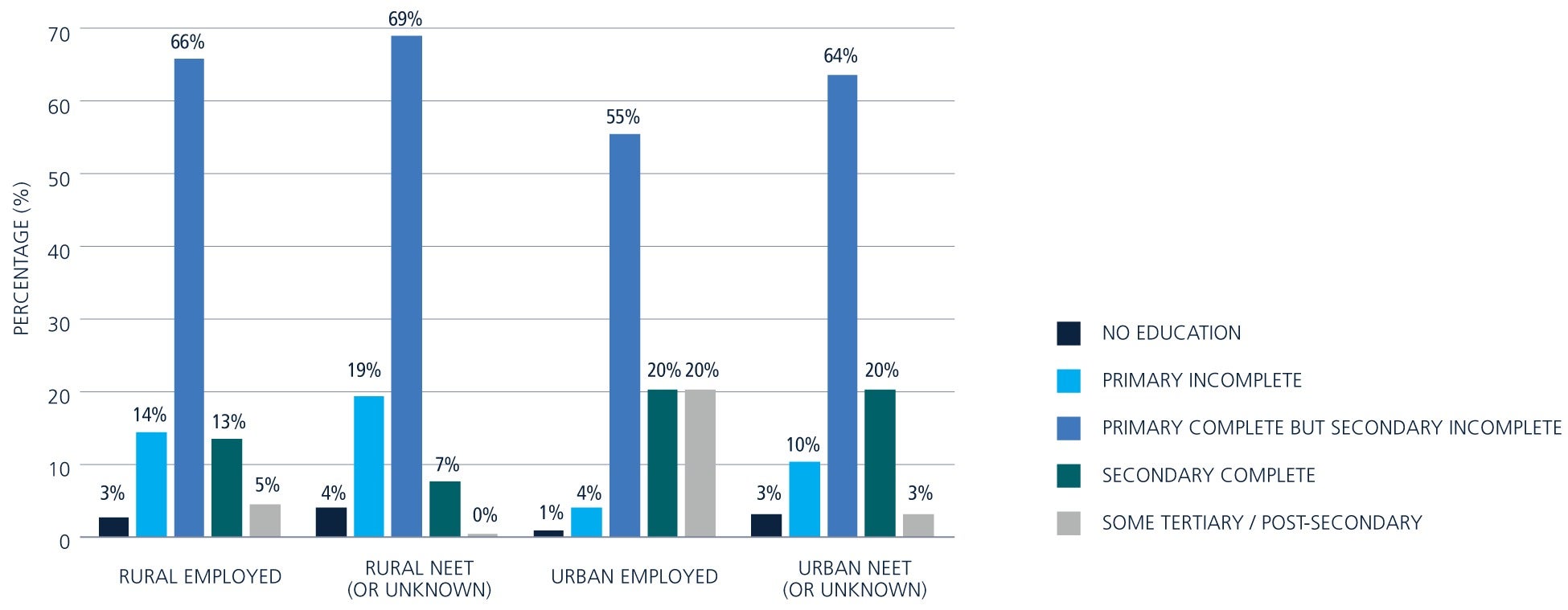

- However, when comparing young working women to young women who are not in Employment, Education, or Training (NEET), we found that more of the women who were working than those who weren’t (55 percent versus 64 percent) had finished primary but not secondary school (Figure 1). This suggests that girls with education attainment do have the possibility to find jobs. Yet, available jobs may not be (good) enough for all women in this group. The problem may be a mismatch between aspirations of female workers and the quality of available jobs, including the degree of security associated with them. In contrast, men — whose social role requires them to support their family — will tend to take whatever job they can get.

Figure 1: Educational attainment of young female NEETs compared to employed young women, 2016

Source: World Bank calculations using the Jobs Diagnostic Supply Side Tool, and I2D2-standardized EPHPM data

Youth are key

The problem of lower female participation in the labor market begins with early school dropout. In 2016, one in every four 15-year-old women had become a NEET. Among the 19-year-olds, half of them were NEETs. In contrast, almost all young men transitioned from school into work by age 18. The act of dropping out is alarming, because once a woman becomes a NEET, it is difficult to later reintegrate into school or work (especially formal work). Women who are out of the labor force miss out on the skill enhancement that comes from working.

If young women think staying at school will not bring them better job opportunities, there is a risk that they will drop out of secondary education. In rural areas, women looking for jobs may be discouraged because they see that half of the jobs are in agriculture and these are mostly taken by men. Similarly, in urban areas the fact that most wage jobs (59 percent) are held by men may discourage women from seeking employment.

Figure 2: Transitions from school to adult life for men and women, 2005 and 2016

Source: World Bank calculations using the Jobs Diagnostic Supply Side Tool, and I2D2-standardized EPHPM data

The take-home message is clear: Better job prospects are needed for the better‑educated youth joining the Honduran workforce, especially for women. Almost a third of Hondurans are below age 15, and another 22 percent are already between 15 and 24 years old. This sizable “youth bulge” represents “workers in waiting.” Unless Honduras expands and diversifies job prospects for women, the country will not be able to reap the returns on its investments in its people through health and education, and to achieve its development goals.

Join the Conversation