motorcycle delivery drivers pack their motorcycles

motorcycle delivery drivers pack their motorcycles

The COVID-19 pandemic took a heavy toll on the global economy, with world output falling by 3.5 percent year-on-year in 2020. Despite these large output losses, surveys from more than 60 countries conducted by the World Bank and partners between April and December 2020 show that nearly half of firms did not make any change — hiring, firing, reducing hours, etc. — to their workforce in the month preceding the survey.

For those firms that did make a change, more than 70 percent of firms chose to do so without relying on firing but by maintaining their workforce and relying on adjustments along the intensive margin, for example by reducing hours or wages, or granting leave to workers. Out of the firms that were interviewed, only about 15 percent of firms overall laid off employees.

Figure 1: Percentage of firms making adjustments to their workforce – By country in the sample

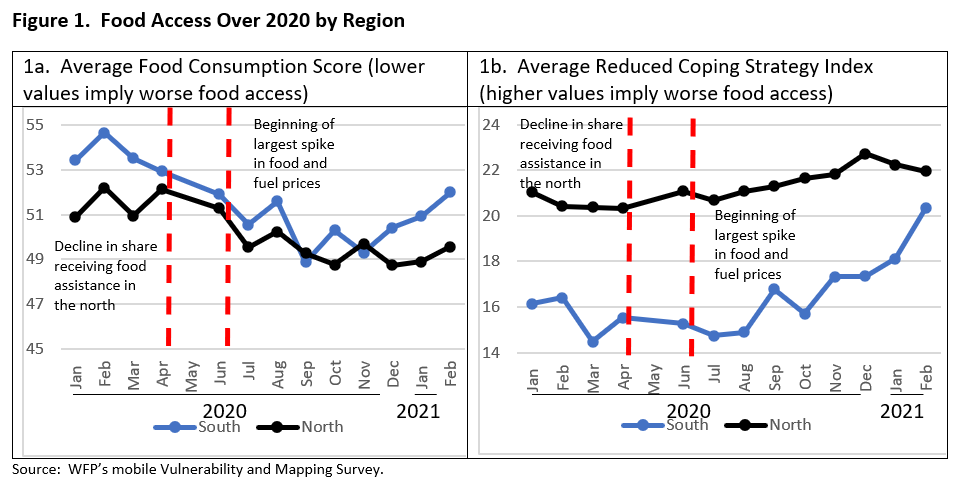

This all seems like good news. However, averages can be misleading and hide large differences across countries. The share of firms making adjustments and the types of adjustment chosen varied widely across countries (see Figure 1).

What may explain these differences across countries? And why did some countries’ workforces fare better than others? We’ve analyzed data from the more than 60 countries surveyed, and here’s what we’ve found.

Stringent lockdowns correlate with more job losses

Government responses to the pandemic included restrictions to movements of people and goods, as well as the temporary closing of businesses.

Countries that had more stringent restrictions, according to the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, were more likely to report a negative demand shock and a larger drop in sales.

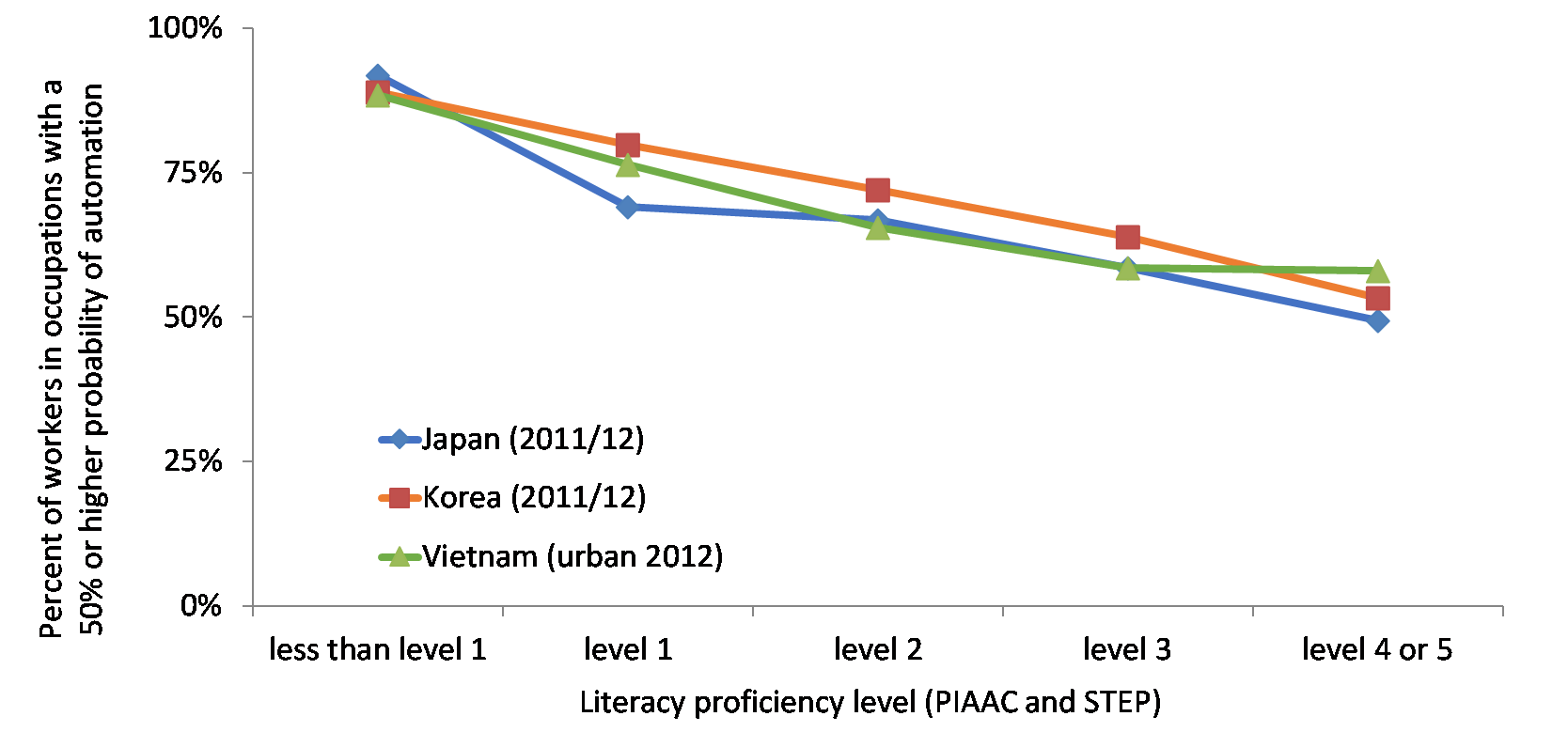

In turn, more stringent lockdown measures increased the likelihood of firms making adjustments to their workforce (see Figure 2). In countries with the strictest measures, firms reported net job losses of about 10 percent of their workers in the month before the survey (after accounting for some control variables). This is more than double the net job losses seen in countries with the least restrictions. Both the stringency of restrictions as well as the economic impact may have been driven by the depth of the health shock that countries were facing, so it’s important not to interpret these correlations as causal evidence.

Poorer countries were hit harder

Firms in lower income countries reported larger job losses than firms in higher-income countries (see Figure 2). This observation is worrying and indicates a possible employment crisis in the countries where social safety nets for the unemployed may be least developed. However, these patterns could be driven by factors that are correlated with a country’s income level, such as labor market regulations or policies to support firms in the crisis.

Countries with strict labor regulations seemed to do better in the short term

In the short term, we found that fewer job losses were correlated with stricter labor market regulations. Using the ILO’s EPLex database of aggregate employment protection, firms with less rigid labor markets reported average net job losses of more than 8 percent of their workforce in the 30 days before the survey (see Figure 2). These net job losses were more than four times as large as those observed in countries with more rigid labor markets. The effects were larger for small firms than larger ones.

In a rigid labor market, on average, smaller firms (below 20 employees) were more likely to adjust their workforce by 9 percentage points than larger firms (above 20 employees).These correlations do not present causal evidence but they are also robust to including controls for a country’s income level, which may be associated with labor market regulations. This descriptive evidence suggests that more protective systems succeed in transferring more of the adjustment cost onto employers in the short term, with uncertain consequences in the medium term.

Figure 2: Country characteristics correlated with average changes in employment

Policies supporting firms are working, for now

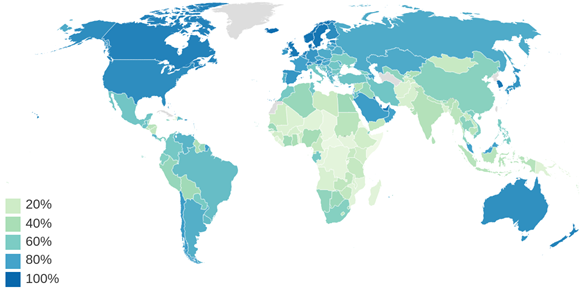

Governments across the world have implemented at least 1,607 measures directly aimed at supporting firms. These range from wage subsidies via changes in loan or tax payments to direct transfers.

We found that good provision and accessibility of government support measures appeared to be associated with fewer job losses in the short term when looking at sector-country observations (see Figure 2). For the group (sector x country) with the largest percentage of firms reporting that they have received wage subsidies, firms reported losing about 3 percent of their workforce. In the other quartiles of the distribution, employment losses were more than double this figure (see Figure 3). While these policies seem to have preserved jobs in the short run, their effects in the longer run – once restructuring is inevitable – are unclear.

Figure 3: Relationship between employment change and the average percentage of firms receiving wage subsidies at the sector x country level

Join the Conversation