Teenage students using computers in a classroom

Teenage students using computers in a classroom

Last week saw the release of new data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), implemented by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Fifteen-year-old students from fourteen Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries participated in this international large-scale student assessment, which was postponed by a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this assessment provide important evidence on what adolescents in the region know and can do in mathematics, reading, and science as well as additional information on how they feel about school, what their learning experience was during the pandemic, and what resources their schools have to provide a good and welcoming learning environment.

For now, we have only had a quick glimpse of the main results, but we wanted to share four key findings for education policymakers and practitioners in the LAC region.

- First,15-year-olds in most Latin American countries face a deep learning crisis with strong socioeconomic disparities. Seventy-five percent of students are below basic proficiency level in mathematics and 55 percent of students are below proficiency level in reading, on average in LAC . This means that these adolescents cannot demonstrate the knowledge needed to participate effectively and productively in society and in future learning. On average, 88 percent of the most vulnerable students in the region are low performers in mathematics, compared to 55 percent among the wealthiest. Gender gaps in performance differ by subject, with boys generally lagging on reading and outperforming girls on mathematics. Considering the importance of strengthening foundational skills during the adolescent years for individual success, including future employability and earnings in the rapidly changing world of work, and for development more generally, these results present a very concerning signal about future productivity and growth potential.

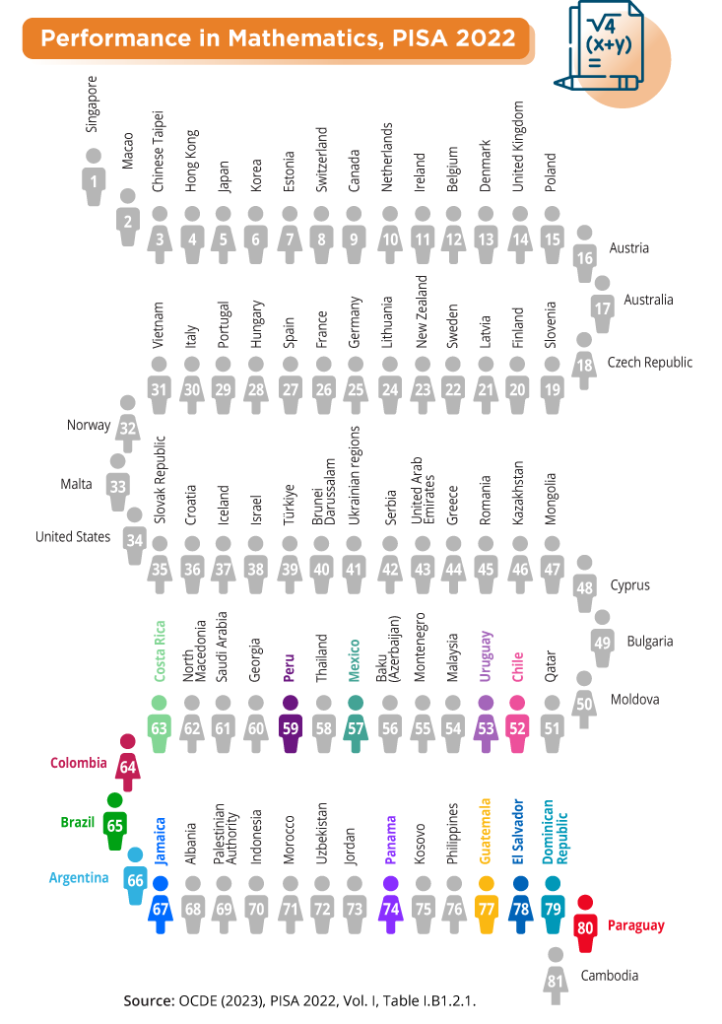

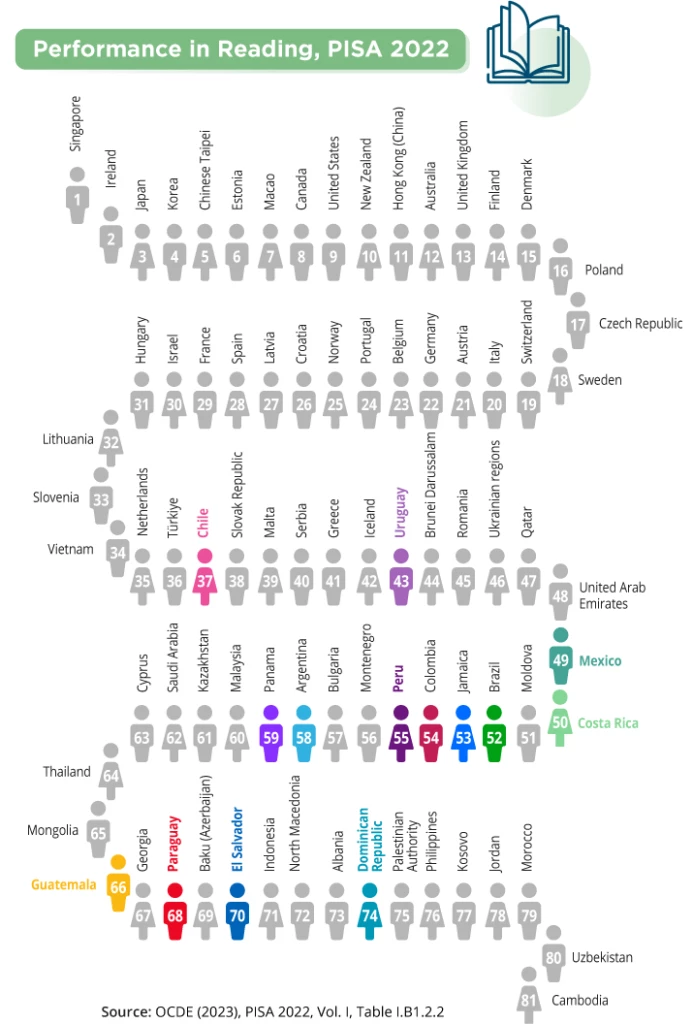

- Second, there is a wide gap in learning outcomes between OECD and LAC students. All 14 LAC countries, except Chile for reading, are ranked below OECD countries (see Figures 1 and 2 below). Using a simple metric, for mathematics, the shortfall in scores of the average LAC student vis-à-vis an average student in the OECD is equivalent to 5 years of schooling.

Figure 1: Latin American and Caribbean students performance in mathematics. PISA 2022

Figure 2: Latin American and Caribbean students performance in reading. PISA 2022

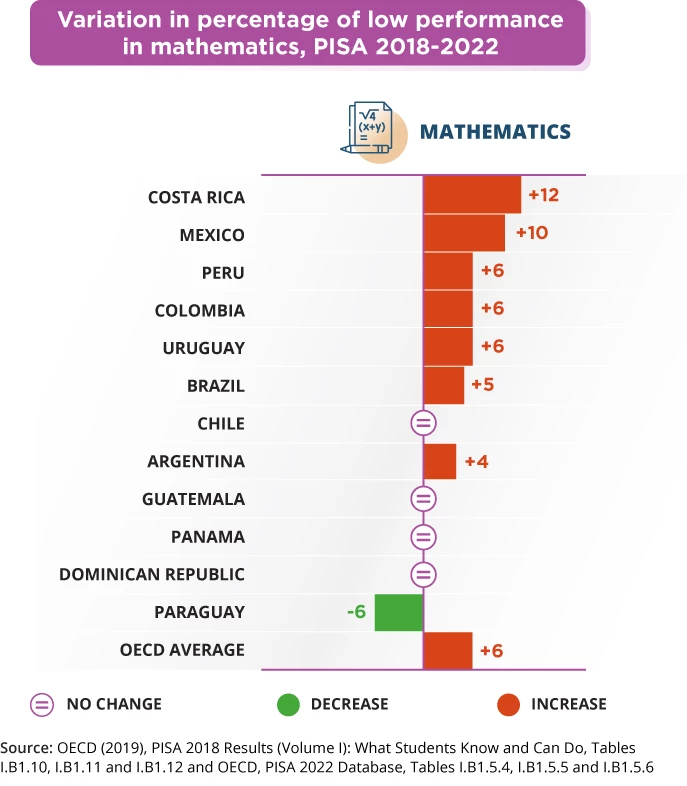

- Third, learning outcomes are not moving in the right direction, and, in most countries, there is an increase in low performance, making it urgent to implement targeted interventions for recovery and accelerated learning . This is particularly evident in mathematics, where compared to the 2018 PISA round, more students have fallen below basic proficiency in 7 out of 12 countries (see Figure 3). These changes are very notable in the context of very low baseline performance in math, since the potential for decline tends to be greater when initial performance is higher (as clearly shown across the countries participating in the PISA 2022 round). Looking at the longer-term trends, in all Latin American countries that participated in 2009 PISA, with the exception of Peru, the share of students below minimum proficiency levels in mathematics in 2022 either remained constant or increased over the last 13 years.The trends for reading and science, however, show more heterogeneity, with increases in low performers in some cases, and stagnation or improvements in others.

Figure 3: Latin American and Caribbean students variation in percentage of low performance in mathematics. PISA 2018-2022

- Fourth, this picture of low and unequal learning levels and setback in learning proficiency between 2018 and 2022 can be only partially attributed to the pandemic losses. The new PISA data is the first international learning assessment after the pandemic, but it also reflects changes from roughly one year before 2020 (two years before for Paraguay, which participated in PISA for Development in 2017) and one year after. But the contribution of the pandemic to this bleak picture can also be validated by the near-universal learning losses observed in primary education for all the countries with updated national assessments. Losses for secondary students are likely to be smaller than for primary school students, as suggested by country evidence confirming also the cumulative nature of skills development. The students we are observing in the 2022 PISA were already 13 by the time schools closed, and they were likely more familiar with technology, access to which was ramped up in most countries of the region, and more able to learn independently. We have been most concerned about learning losses, among children in early childhood education ages and, for schoolchildren in grades 2 to 6, since foundational literacy skills are acquired during those grades, and if recovery does not continue, we may see large gaps in the next PISA round. Finally, and interestingly, some countries have already started to recover learning by 2022, building on the growing commitment of LAC countries to learning recovery and acceleration and the actions already taken in 2021 and 2022 by some of them, such as the prioritization of curricula on foundational skills, the targeted support to low achievers, and the enhanced technology deployment.

- In view of the very high shares of students below basic proficiency and the negative trends in mathematics, take immediate action to recover the learning losses in math outcomes for adolescent learners, including tutoring interventions, potentially using EdTech solutions.

- Take action to improve and strengthen outcomes in other subjects (including reading and science), ensuring that half of the students who are lagging behind can catch up.

- Continue to emphasize recovery and acceleration efforts in reading and math for primary education students who have been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and who would be part of the next rounds of PISA assessments.

Policies cannot be implemented if the right level of resources is not allocated. OECD countries invest per student on average three times as much as LAC countries over their learning trajectory: $102,612 versus $36,972. But not only increasing investments is important. Countries should also spend better: in all countries in LAC with data, performance in math is below what their level of investment predicts.

The World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank are looking forward to digging deeper into the PISA data to understand how 2022 results and changes from the 2018 wave differ by different student and school characteristics, including access to digital technology in the learning process. This analysis will be carried out jointly. Stay tuned.

[1] These include Argentina (APRENDER, 2018, 2021, 2022); Brazil (SAEB, 2019, 2021); Chile (SIMCE, 2018, 2022); Ecuador (Ser Estudiante, 2021, 2022); Peru (EM, 2019, 2022); Uruguay (Aristas, 2017, 2018, 2020, 2022); Mexico, Guanajuato (RIMA 2020, 2021).

Stay updated with our weekly article

Related articles:

Join the Conversation