A girl from Barbados receive a vaccine

A girl from Barbados receive a vaccine

Countries around the world are lifting COVID restrictions, schools and workplaces are opening, and mask-wearing and COVID-testing are no longer necessary for many international flights.

However, the pandemic is not yet over. Countries are still experiencing new waves of infection. Overall, there is uncertainty about what the end of the COVID-19 pandemic will look like.

Vaccination remains one of our main tools to manage the shift from pandemic to endemic. However, in the Caribbean, governments are struggling to vaccinate much of their population.

COVID-19 vaccination campaigns in the Caribbean had a slow start. Immunization picked up, but most countries are falling short of the World Health Organization (WHO) 70 % vaccination target. Eight of 20 countries in the Caribbean are below a 50 % vaccination rate - Dominica, Suriname, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Lucia, Jamaica, Haiti, and the Bahamas. Only Aruba, Turks and Caicos and the Cayman Islands met the WHO target– all which are high-income countries.

For Caribbean countries, high vaccination rates are essential because of the vulnerability profile of their population and their dependency on tourism. Caribbean countries have among the fastest aging populations in the developing world, according to PAHO, and one of the highest levels of global inequities in health outcomes, putting much of the population at higher risk of severe COVID-19.

Whereas limited vaccine supply was initially a reason for low vaccination rates, this is no longer the case. Now, vaccine acceptance and uptake represent the main roadblock in the Caribbean vaccination journey. According to recent High Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS) administered by the World Bank and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Caribbean countries stand out in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region for having the highest shares of unvaccinated people who are unsure about vaccination or do not plan to vaccinate (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of population that are unsure about or do not plan to be vaccinated against COVID-19 (among the unvaccinated population) (Nov – Dec 2021)

Why are people concerned about being vaccinated against COVID-19?

The HFPS data tell us more about the reasons for the comparatively low COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and uptake in the Caribbean. The main reasons were concerns around the risks of vaccines with few perceived benefits and issues related to trust. Specifically, many people did not feel they were at risk for COVID. Others were worried about side effects and/or limited vaccine effectiveness and felt they lacked information. People without internet access were more worried, which might suggest that vaccination concerns may be more common in households isolated from easy access to information.

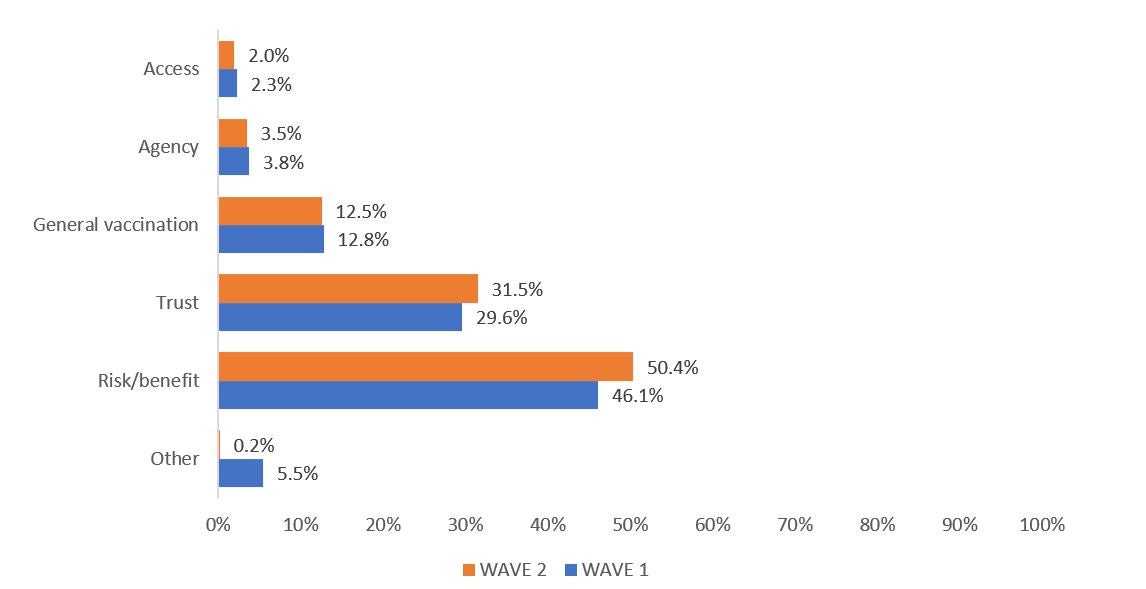

Figure 2: Main reasons for being unsure or unwilling to take a COVID-19 vaccine

The data also show positive developments between mid- (wave 1) and end-2021 (wave 2). Vaccine acceptance and vaccination rates improved among the unvaccinated across all ages. The largest improvement in vaccine acceptance and uptake occurred among older adults (55-64 age group). Knowledge of how to get vaccinated also increased.

How to increase vaccine acceptance and uptake in the Caribbean?

A first step is combating the “infodemic” by providing accurate information on the risks and benefits of vaccination to address the concerns of unvaccinated people. Accurate, transparent information must be communicated through various mediums to reach different populations, including those without internet. Relatedly, it is extremely important to counter false narratives in the region to mitigate the impacts of misinformation on vaccine decisions and to increase trust in the vaccine approval processes and in health systems.

But combating the info-demic is not enough. We need to know more about country-specific socio-behavioral motivations and constraints to vaccination.

In an effort to gain insights into people’s perceptions of COVID vaccines, the World Bank’s Mind, Behavior and Development Unit (eMBeD) launched social media surveys in Belize, Haiti and Jamaica. Behavioral insights from these surveys can further inform the crafting of tailored communication messages.

Caribbean governments have taken up the challenge. Ministries of Health and their dedicated communication teams developed and implemented a multitude of targeted communication and outreach efforts to increase vaccine acceptance and uptake. For example, Belize deployed various interventions that contributed to high vaccination rates, such as: sending of mobile units to provide door-to-door educational sessions in remote villages prior to the arrival of vaccination teams, information-sharing via social media, and using radio to reach those without internet.

However, these efforts are often limited by the human and financial constraints of overburdened health systems, and by the lack of knowledge of what interventions worked.

Existing efforts can be further refined and targeted using the increasing evidence and lessons learned on the ground from countries. However, two key gaps need to be filled to take the challenge to the next step.

First, there is need to complement online surveys with in-depth qualitative research to identify sub-populations and their specific vaccine concerns. Second, the global health community can work together to build evidence on ‘what works’ in convincing those who are unsure or unwilling to actually get shots.

These will be critical steps towards developing effective local and multi-pronged demand-promotion strategies to target barriers to acceptance—moving the needle where progress has stalled and to get shots into arms.

Join the Conversation