Bonaire aerial view.

Bonaire aerial view.

We have heard about the challenges many Caribbean islands have faced over the unprecedented past 18 months. Not only have they battled an ongoing pandemic with its many complications and variants, but many have also tackled compounding hazards of drought, heavy rains, storms, and with ensuing floods and landslides during the Atlantic hurricane season. Some have recently also grappled with the impacts of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes.

However, within the region, there is a smaller group of islands not often discussed that also face their own unique, complex realities – Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs).

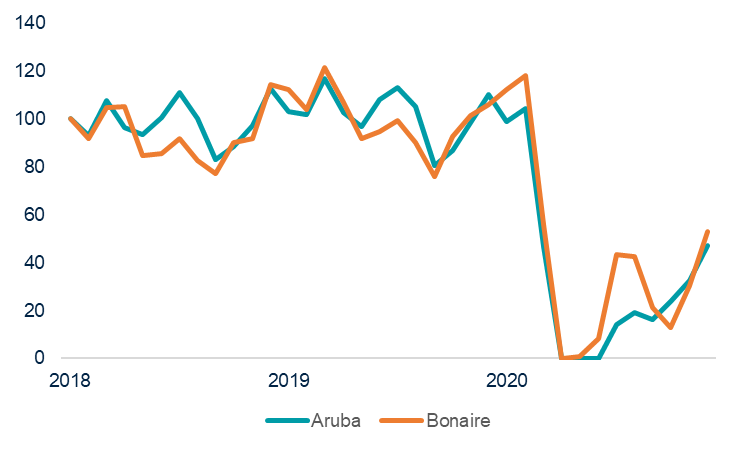

Caribbean OCTs – such as Aruba and Bonaire – are not sovereign countries; rather they depend to varying degrees on countries in Europe and North America, particularly the Kingdom of the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Due to their geographic location, OCTs remain critically intertwined with the Caribbean region through transport and trade routes, culture, and migration. And like many Caribbean countries, their economies are heavily concentrated on tourism (Figure 1) rendering them particularly vulnerable to external shocks, like pandemics, and measures such as border closures.

Figure 1: Index of inbound tourism to Aruba and Bonaire by air (January 2018=100)

(Source: Statistics Netherlands, Central Bank of Aruba)

However, unlike many other Caribbean islands, Dutch Caribbean OCTs typically have limited access to the regional and international initiatives and development partners that support the region, and so rely primarily on resources from the Netherlands. They also usually have limited disaster management capacity on-island to prepare for and respond to disaster events.

For this reason, the World Bank, through the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, is partnering with the European Union and Expertise France on the Technical Assistance Program for Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance in Caribbean OCTs, which is part of the EU-funded Caribbean OCTs Resilience, Sustainable Energy and Marine Biodiversity Program (RESEMBID). This program helps them enhance their financial resilience to disasters and identify capacity-building strategies based on each OCT’s needs.

The case of Aruba and Bonaire

The governments of Bonaire and Aruba responded swiftly after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic and took action to minimize the virus’ impact. They halted flights and cruise ships, closed schools, and canceled public meetings. This decisiveness minimized the pressure on the healthcare sectors and likely slowed the direct impact of COVID.

However, these measures in the end proved insufficient to contain an eventual surge in active cases of COVID-19. The subsequent impacts of the pandemic have included closed borders and a major reduction in tourism arrivals. Downturns in other productive services shocked the islands’ GDP and highlighted the vulnerability associated with strong tourism dependence (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Estimated Real GDP contraction in 2020

(Source: Central Bank of Aruba, Statistics Netherlands, World Bank)

The pandemic led both governments to request support from the World Bank, through the RESEMBID program, to inform their COVID-19 response and recovery measures.

In Bonaire, a Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) was conducted to evaluate the effects of COVID-19 on critical areas such as macroeconomic management, tourism, commerce and industry, agriculture logistics, environment, and disaster risk financing measures.

The subsequent analysis of Bonaire’s 2020 macroeconomic performance revealed an estimated 19% contraction in real GDP and highlighted that without the US$67.4 million financial intervention from the Netherlands, the economy would have likely spiraled into an estimated 36.2% downturn in 2020.

Key recommendations that arose from the PDNA included the continued need for financial assistance to businesses, the re-design and scale up of social benefits to protect livelihoods, the strengthening of agricultural logistics, and the set-up of a broad asset management database and central registration of inflow of funds to inform effective disaster risk financing.

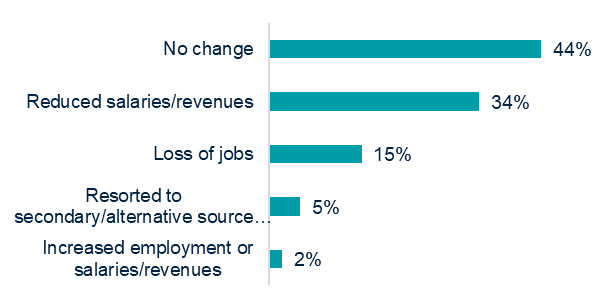

For example, a large share of the population reported a negative change in income as a result of the pandemic (Figure 3). The PDNA analysis also pointed to an unmet need for programs that address food security, housing support, psychosocial care, and childcare. As a result, and informed by the findings of the PDNA, the Island Council of Bonaire petitioned the Dutch government to raise its subsistence level to counter the regression in livelihoods following COVID-19.

Figure 3: Bonaire: Change in income as a result of the pandemic

In Aruba, since 90% of its economic activity is dependent on tourism and the agricultural sector contributed to less than 0.5% of GDP at the onset of the pandemic, the government was concerned that the COVID-19 crisis could potentially pose risks to food security and livelihoods. It, therefore, requested an assessment that would offer strategies to strengthen resilience in its food supply chain. This assessment, Building Resilience in Aruba’s Food Security During the Covid-19 Pandemic and Beyond allowed the Department of Economic Affairs and the Department for Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (Santa Rosa) to deliver a plan that was later approved by the Council of Ministers to operationalize the recommendations.

For both islands, these analyses provided the tools needed to have in-depth dialogues with partners and stakeholders around recovery efforts. The findings and recommendations can also be useful for other OCTs and the wider Caribbean region as countries evaluate how to better secure economies and livelihoods and build resilience against future health and natural hazards.

Join the Conversation