With a 7% economic contraction, 30 million people became unemployed or were left out of the labor market in 2020. It is very painful to show such figures, especially when we had hope for a faster recovery. But well into 2021, the effects of the pandemic are still not under control in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Though the rollout of vaccination campaigns is helping governments to address the health crisis, they are still grappling with how to address the economic fallout, including how to help vulnerable workers going forward.

Our recent study Jobs Interrupted: The Effects of COVID-19 in the Latin America and the Caribbean Labor Markets aims to inform the policy dialogue by answering three key questions using labor market data from the onset of the pandemic:

Who were most affected by job losses?

Unfortunately, the already vulnerable—those less ready to cope with economic shocks. Everyone lost out in the pandemic. But some vulnerable workers, those with types of jobs and characteristics that make them less resilient to economic shocks (informality, lack of experience, low-income, among others), lost more.

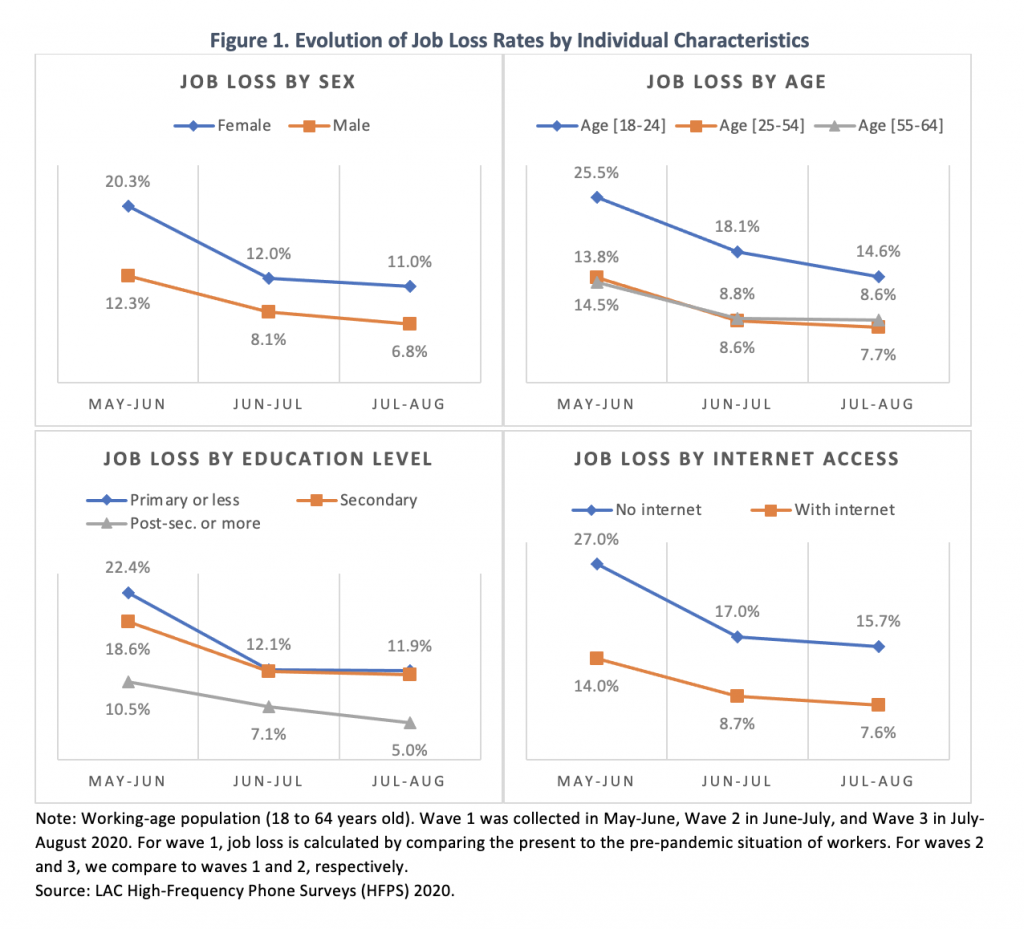

Factors such as gender, education, connectivity, and experience played a critical role in determining how a person fared during the crisis.

Two months into the pandemic, in May of 2020, about 20% of working women had lost their jobs. School closures and the increase in childcare responsibilities at home detached women from the labor force. Moreover, there were important contractions in the industries in which women are predominantly employed (such as accommodations, food preparation, and tourism).

One in four workers with only a primary education lost their jobs. And the odds were similar for those without internet connectivity at home. In addition, the pronounced economic downturn and uncertainty has limited entry-level hires, affecting workers under 25 years of age, one quarter of whom lost their jobs, potentially affecting their income trajectories in the future. And, unfortunately, the unequal burden of job losses persisted over time (Figure 1).

What happened to those who remained employed?

Many were temporarily absent from work! Contrary to what had been widely hypothesized, people who managed to stay employed did not do so by switching to lower quality jobs at the beginning of the crisis.

On average, only 5% of the employed population switched from their pre-pandemic jobs to new jobs. Also, transitions between types of employment were relatively small. Reassuringly, we do not see evidence of large numbers of workers leaving (or having to leave) their wage jobs to become self-employed.

What did occur, however, was an increase in the number of absences from work – followed by job losses. People who were not working but had a job they expect to return to – so called absent workers- are traditionally considered as part of the employed population.

The pandemic increased the number of absences and the uncertainty as to whether and when people could return to their jobs. A quarter of workers were absent in May 2020. Only half of them went back to work by August. This result underscores the vulnerability associated with this “employment” status (i.e., absence from work). Unfortunately, evidence from previous crises suggest that negative shocks can have lasting effects on the structure of employment.

What can be done?

Increase digital connectivity, allow work flexibility, and upskill workers. These could help address some of the problems brought by the pandemic to the labor markets.

In the short term, governments have made significant efforts, such as activating social protection policies, to buffer the impacts of the crisis. Financial support and flexible work schedules will likely continue to be necessary. Governments can also provide subsides to lower the cost of hiring certain types of vulnerable workers and address labor regulations that could slow down the recovery.

In the medium term, programs to upskill workers might be needed to reintegrate them in the labor force; parents would benefit from expanded access to childcare services that allow them to balance professional and household responsibilities; and economies would benefit from expanding digital connectivity and increasing affordable access to the internet.

Join the Conversation